The makers of a new OTT offering—Ashim Ahluwalia and Kersi Khambatta—on how they manoeuver through the rugged and controversial terrain of caste and class through young eyes

National-award winning director Ashim Ahluwalia says he didn’t want to make a singular theme show, but display daily lives of Indian kids

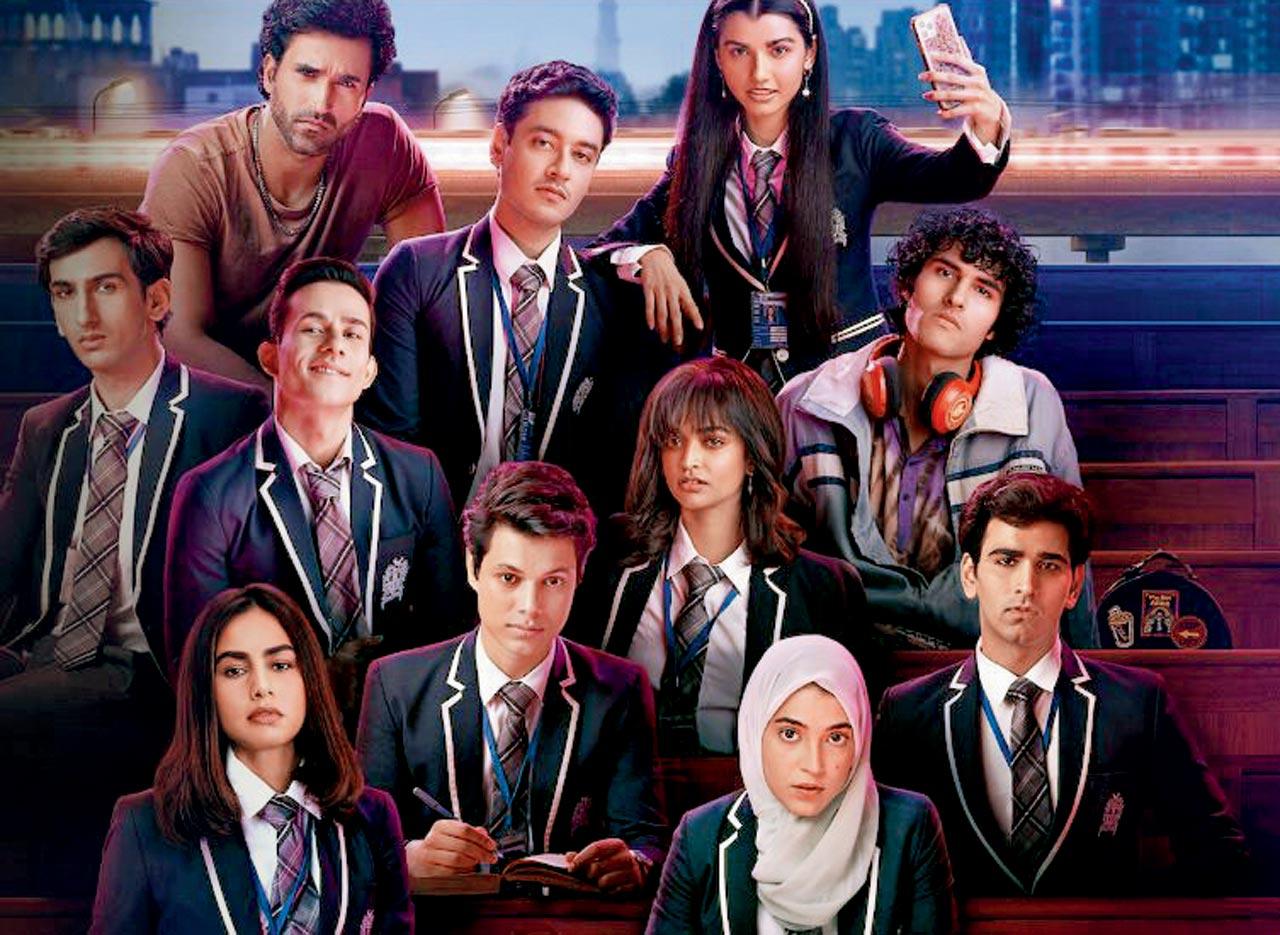

Love it, like it, or find it overloaded with themes layered like Medusa’s tresses, but you cannot miss the new series on Netflix, Class.

ADVERTISEMENT

On a weekday, we sat down for a chat with showrunner Ashim Ahluwalia and screenplay writer Kersi Khambatta about the eight-episode murder mystery revolving around the lives of young adults in Delhi, and it smoothly transitioned into a conversation about caste nuances, class privilege and character representations. An adaptation of the Spanish show, Elite, Class is a story of three students from poor backgrounds, who get into an uber-rich school on scholarship, and their interaction with the other students.

Ahluwalia says he never set out to adapt Elite, nor had he watched it until requested to. “Class represents India right now. I was keen to make something around rebellious teenagers,” says the maker of Miss Lovely, “because I was one. Even though the Spanish original is glossier, I found the characters and situations intriguing and decided to stick with the plotline, almost like a novel source, and create a more realistic Indian version.” Peppered with his own childhood experiences in Mumbai, Ahluwalia says the screen depiction of rich kids and their parents is not far from reality.

Class, an adaptation of Spanish show Elite, is about young-adults in Delhi, sorrounded by the dynamics of caste, class, religion, sex, drugs and drama

Class, an adaptation of Spanish show Elite, is about young-adults in Delhi, sorrounded by the dynamics of caste, class, religion, sex, drugs and drama

“In a metropolis,” says the National award-winning director, “we all come across spoiled, wealthy children. Some people might express reservations about showing children in such light; I’d ask them to Google ‘Delhi school scandals’. Everything is out there—MMS scandals, brats running people over and getting away with it, even rape threats. Perhaps our version is softer.” “There was no time for soft touch, over thinking, or over justification of character motives,” interjects Khambatta, “We wanted to hit hard, get the message across, keep the pace and all the fluff away.”

The message is quite clear, really. “Caste, class, religious and financial disparity is out there in the real world; there’s no denying it,” says Ahluwalia, adding, “We didn’t want to be preachy. You can be pro one community and anti another, pro gay or not, but our audience can have their own point of view. We are not telling anyone how to think, just showing a multilayered world that exists.”

Khambatta’s filmography includes Being Cyrus and Finding Fanny—both with friend Homi Adajania—with them alternating the roles of director and writer. “You open the newspaper and these issues [caste, religious and gender discrimination] are in there,” is his perspective, “It is what some Indians deal with every day, and while most shows have only skirted the issues in an effort to be politically correct, we wanted to hold up a mirror to society.” Discarding the accepted pattern of a one-theme show, the makers say theirs isn’t about “homophobia, Islamophobia, Dalit rights etc, but just about a bunch of kids and what they deal with every day”. It’s the several Indias within one India.

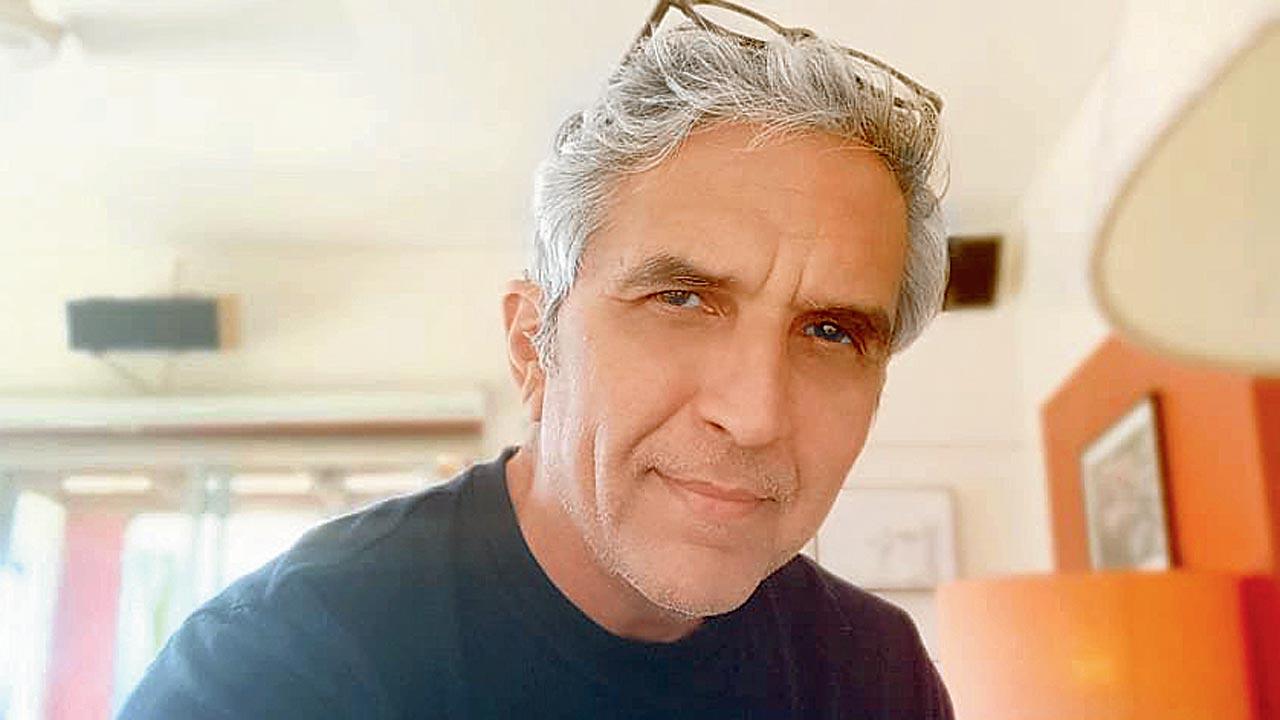

Kersi Khambatta, writer-director

Kersi Khambatta, writer-director

And while Khambatta is less hopeful about change, Ahluwalia believes the good and bad co-exist. “The fact that we have such a show running,” he points out, “and that conversations around caste and religion can take place, is encouraging in itself. I don’t think this would have been possible 20 years ago.”

Joking about the realism of their characters, Ahluwalia says that a number of his acquaintances have wondered whether the characters or situations are based on them. He laughs it off. “The original show did not have the parent angle,” he says, “I introduced it considering that if the children are this wild, what would the parents be like? Many [viewers] have appreciated this aspect.” Both makers are aware of the responsibility of how sex is shown on screen, and the role social media plays. “In India,” says Ahluwalia, “most works depicting sexuality are voyeuristic. The same goes for some western shows, where people fast forward to the scenes of nudity, sex and skin. We wanted to deal with sexuality through the eyes of the characters and the narrative. Teens experiment and grow through such acts into adults, but we didn’t want to exploit these [to grab eyeballs].”

Khambatta has the last word: “The younger generation is all about the Internet; their acceptance in society and insecurities are all driven online. The Internet has given people a voice beyond control. Social media explosion should reflect in every show now because it is a part of all our lives, and more so for teens, who practically live online for most of their waking hours.”

Watch: Netflix’s show Class creators on representing all sides of India today

Also Read: How pastels are redefining the traditional narrative for Indian brides

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!