A German communist arrived at city’s shores a century ago. Across three decades, the growth of the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group and an obscenity case, there was no churning in art that he shied away from

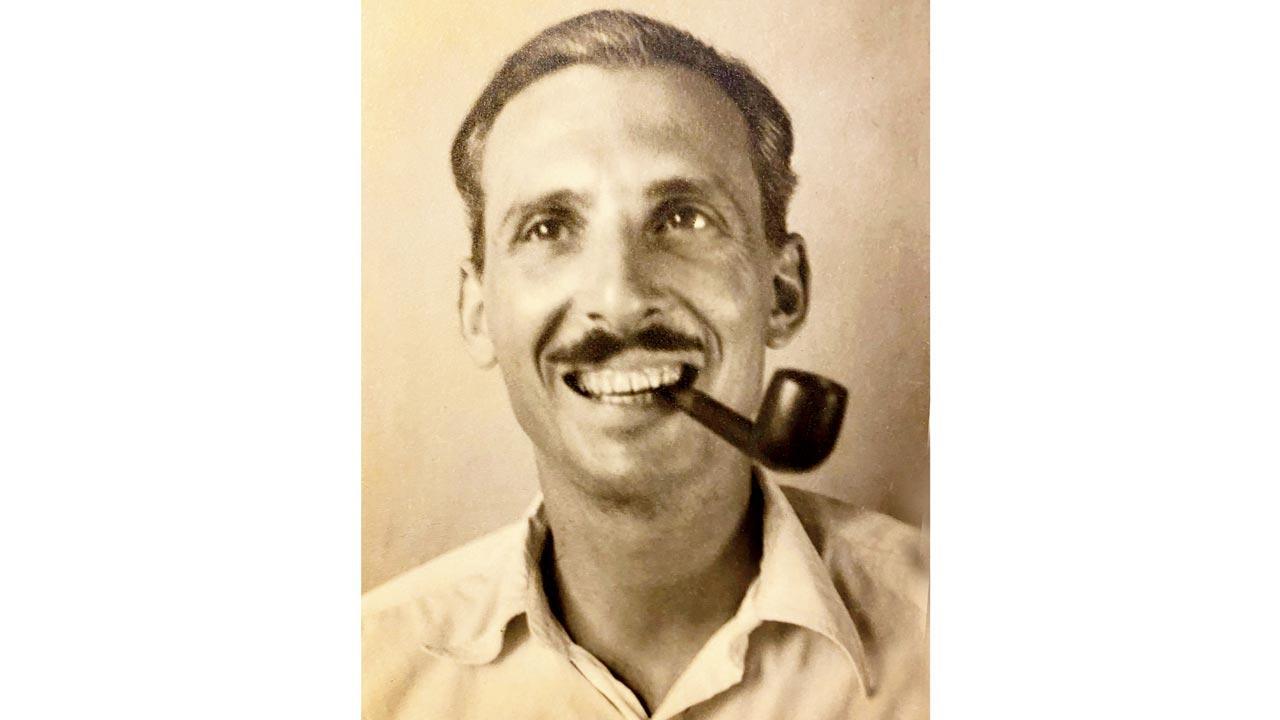

Not only did German-born von Leyden have a nuanced understanding of Indian aesthetics, he also identified promising artistic talent in its nascent stages. Pic Courtesy/James von Leyden

In autobiographies—of artists, business tycoons, and politicians—it is the most significant players who move the story forward. The crossing of paths with allies, enemies, mentors, and lovers enriches books, bringing out the best and worst in their subjects. The Acknowledgements, on the other hand, are an entirely different matter; here, people closest to the subject enjoy pride of place.

ADVERTISEMENT

Rudolf von Leyden, a German émigré who made Bombay his home in the turbulent 1930s, is the sort of friend who’d feature in the Acknowledgements of many stories. Still cherished by those who knew him, and a recurring name in the archives of Mumbai’s cultural institutions, he influenced a number of famous lives—in big and small ways—from painter Krishnaji Howlaji Ara, to ad man and thespian Alyque Padamsee.

The Catalyst (Speaking Tiger), Reema Desai Gehi’s new and engaging biography of von Leyden, details how he was targetted in post-World War I Germany for his Communist leaning and Jewish roots, and why he chose to seek refuge in Bombay, when pursued by the Gestapo. Drawing from diaries, letters, interviews, and family archives, the writer paints a dual portrait: Of the ways in which von Leyden became an integral player in pre- and post-Independence Bombay’s arts and advertising scene; and the city’s wholehearted embrace of him as a Renaissance man, in return.

Her seven-year-long effort to retrace Rudolf von Leyden took art writer Reema Desai Gehi across the world. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Her seven-year-long effort to retrace Rudolf von Leyden took art writer Reema Desai Gehi across the world. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Desai Gehi includes a variety of colourful details—of evenings spent at Willingdon Sports Club or swimming at Juhu beach.

Kekoo Gandhy, co-founder of Gallery Chemould, recalls how “Rudi” would rush from gallery openings to the office of the newspaper he wrote art reviews for, on his bicycle. Rudi’s engagements with the arts and theatre continued even as he worked in the advertisement and publicity wings of companies such as Voltas.

“What struck me about Rudi’s art writing,” Desai Gehi says, “was that it was coherent and bereft of jargon. And it was so relevant—I thought to myself, this is exactly how I aspire to write. Skilful language, still nuanced and accessible. I was also struck by his writing’s historical value, because he reviewed practically every premier artist of his times.”

(Standing – L to R): Käthe Langhammer, Rudi with Nena (middle); Walter Langhammer and Ebrahim Alkazi; (Seated – L to R): Husain, Bakre, Gade, Ara, Souza, Raza and Mulk Raj Anand. Pic Courtesy/James von Leyden

(Standing – L to R): Käthe Langhammer, Rudi with Nena (middle); Walter Langhammer and Ebrahim Alkazi; (Seated – L to R): Husain, Bakre, Gade, Ara, Souza, Raza and Mulk Raj Anand. Pic Courtesy/James von Leyden

Krishen Khanna, who has penned a personal, hand-written foreword to The Catalyst, is the very reason Desai Gehi was alerted to Rudi’s work as an art critic. “[Walter] Langhammer [Austrian artist and fellow émigré] became the great chachaji of painting in Bombay. When Langhammer came in, Ara and [SH] Raza would get scared, but when Rudi came in, they wouldn’t. Rudi could always talk down to the point,” Khanna said to the writer.

If Langhammer was chachaji, Rudi was a kingpin. “One of my interviewees called him a ‘universal gebildet’, a German phrase to mean someone who is culturally refined and erudite… His interests were varied and many,” says the art journalist and editor, who devoted seven years to retracing Rudi’s life.

In the early pages of The Catalyst, Desai Gehi deftly narrates how von Leyden stepped up and offered to be a defence witness in an iconic obscenity case of the 1950s. A young and fiery Akbar Padamsee, whose works were being exhibited at the Jehangir Art Gallery, painted the image of a couple in the nude, with the man touching the woman’s bare breasts. The Vigilance Branch of the Bombay CID took umbrage and confiscated two paintings; Padamsee looked far and wide for peers who would support him publicly.

On June 16, 1954, Rudi took a combative stance and declared in the Court of the Presidency Magistrate that Padamsee’s “obscene” depiction of human love shared similarities with artistic depictions across the world, but especially ancient India—in the sculptures of the Khajuraho temple. His formidable defence was pivotal to the painter winning the case.

This episode lets the reader into two of Rudi’s strengths, his unwavering support to the cause of Indian art, and his nuanced, discerning grasp on Indian aesthetics—a result of a sustained interest in architectural marvels and sculptures. “The relationship he shared with artists like Khanna was not like a regular relationship between a critic and artist. It was a familial relationship of equals,” Desai Gehi says, adding that he encouraged the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group to create works that spoke to their milieu and moment, rather than following in the footsteps of European painters.

Interestingly, Rudi acknowledged the shift in his own gaze. “‘I liked the country [India] and its people from the word go, but I now realise that my initial attitudes were very sahib, and that friendships begin when the sahib disappears,” he introspected.

Another trait that made Rudi, who was originally trained in Geology, singular in the art scene was his ability to recognise the talent of artists like SH Raza, Gieve Patel, and Nalini Malini in the nascent stages of their careers. “He responded to art intuitively… He saw their sincerity,” Desai Gehi remarks. This is why he acted when another critic disproportionately praised FN Souza in 1963. “He knew when work came from instinct and when it was a gimmick,” she adds.

Even as his guidance to artistes such as Alyque Padamsee, whom he encouraged to work with Indian scripts, shaped their oeuvres, von Leyden’s own name remains conspicuously absent in popular discourse—a footnote in the retelling of popular history instead of being a protagonist. “There are many who came during World War II to Mumbai because a number of circumstances brought them here, as they continue to. They impact people and they become obscure names. It’s important to document them, because these are the hidden histories,” Desai Gehi concludes.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!