As churches and graveyards are attacked in the city and across the country, the community, yet again, is forced to defend allegations of forced conversion

Around 18 crosses were vandalised by a man from Navi Mumbai at St Michael’s church in Mahim on Saturday, using brute force. Many of these crosses were more than 100 years old. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

The Mahim parishioner was dawdling away on a Saturday when she received a call from an uncle at 9 am. “Someone has broken the 100-year-old tombstone on your grandmother’s grave,” said the voice on the other end. I was shocked, disturbed and saddened,” she says. After saying a short prayer, she and her husband set off for the cemetery at St Michael’s Church in Mahim where her grandmother lay.

ADVERTISEMENT

This cross, laid down by *Sharon’s grandfather in 1918 when his young wife passed away, was part of the family plot where her grandparents and parents were also laid to eternal rest. “I kept asking myself, why would anybody do something this awful? If it was a robbery, one knows the intention, but what can anyone gain from vandalism?” she laments. Just the year before, the family had the Italian marble cross polished to commemorate her mother’s death anniversary.

A candle-light march takes place in Bandra West. Pic/Atul Kamble

A candle-light march takes place in Bandra West. Pic/Atul Kamble

Sharon’s family cross was one of the 18—many of which were over a century old—to be vandalised on January 7. St Michael’s Church is counted as both, one of the oldest Catholic churches and one of the oldest standing Portuguese buildings in Mumbai. It was constructed in the 16th century and restored to its present form in 1973.

The perpetrator, later identified as Dawood Ansari, had allegedly leapt over the cemetery wall in the early hours. The 22-year-old from Navi Mumbai was apprehended by the police the next day, and booked under IPC Sections 295 (defiling a place of worship with intent to hurt a religion) and 447 (punishment for criminal trespass).

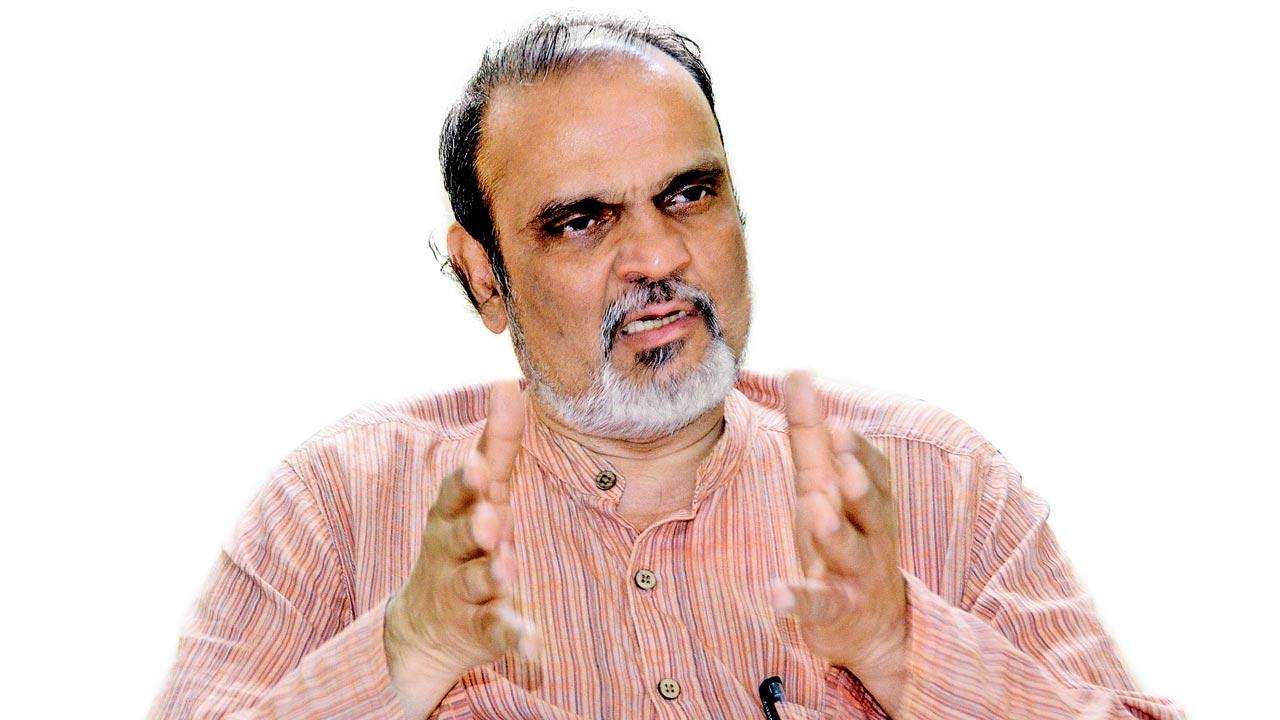

Father Bernard Lancy Pinto, parish priest of St Michael’s Church believes Christians are being targeted for alleged forceful conversion even though there is no data to prove a rise in Christian population

Father Bernard Lancy Pinto, parish priest of St Michael’s Church believes Christians are being targeted for alleged forceful conversion even though there is no data to prove a rise in Christian population

“The attack,” says Father Bernard Lancy Pinto, the priest of the parish, “took place even before the morning mass began at 6 am. The CCTV footage shows him kicking and uprooting tombstones. A parishioner alerted the guard as Ansari was jumping back over the wall to escape. Ansari turned around, said he had come to pray and went inside to attend mass. After a while, he went up to St Michael’s statue in the hall and casually walked out with his bag.”

Fr Pinto was told about the vandalism after mass, at around 8 am. The guard had the presence of mind to take a picture of the vandal, which was handed to the police. “They say the accused isn’t responding, and looks dazed and confused,” the priest tells us when we meet him at the church. “Why would someone travel over 37 km, from Kalamboli to Mahim, for this? What’s the motive? Was this due to the Bandra protest [over land-acquisition for road widening]? We don’t know whether this comes in a series of such incidents, or is a one-off job.”

Members of the Bombay Catholic Sabha took out a peaceful protest march against the claiming of cemetery land of St Peter’s Church in Bandra West. Pic/Atul Kamble

Members of the Bombay Catholic Sabha took out a peaceful protest march against the claiming of cemetery land of St Peter’s Church in Bandra West. Pic/Atul Kamble

Spokesperson of the Archdiocese of Bombay, Father Nigel Barrett, says, “It is not for us to decide the reasons [behind this act] but the community is deeply hurt. Along with destruction of religious objects, it also disrespects the dead.”

On January 2, the BMC had issued notices to the century-old St Peter’s Seaside Cemetery in Bandra West and the Bandra Bene Jewish Cemetery, for taking up a portion of their land for road-widening. Of the 400 graves at the St Peter’s Cemetery, 30 would have been affected.

Father Donald D’Souza, Dolphy D’Souza and Father Nigel Barrett

Father Donald D’Souza, Dolphy D’Souza and Father Nigel Barrett

Both communities protested peacefully and the notices were withdrawn. The matter is being reconsidered. On the same day, a church on the premises of a school in Chattisgarh’s Narayanpur district was also vandalised when two tribal communities clashed over alleged religious conversion. On December 27, 2022, the statue of baby Jesus was damaged in Mysuru, Karnataka. The burning of Santa Claus effigies ahead of Christmas by fringe groups, has increased across the country in the last few years.

While the sequence of these events may be coincidental, the Christian community is unsettled. As a minority, will they be the next target?

“The propaganda of hate,” says president of The Bombay Catholic Sabha Dolphy D’Souza, “that has been unleashed in the country dividing it on religious lines, has resulted in situations where anti-social elements are taking law and order by its neck. Such incidents happened in the past too, but we have noticed them to be on the rise in the last eight to 10 years.” D’Souza demands stepping up of vigilance by the state and the police as part of their responsibility to ensure safety of all people across faiths. “We met DCP Manoj Patil,” he adds, “and appreciated that the culprit was apprehended within 24 hours, but we have also urged them to do a thorough investigation into the motive for targeting a prominent shrine revered by devotees across communities and faiths.”

According to New Delhi-based NGO, United Christian Forum, there have been over 300 attacks on Christians between January and July 2022. The number is based on data collected from distress calls on its helpline number. In 2015, in Uttar Pradesh, the Christian community observed Black Day to peacefully protest growing atrocities and desecration of churches. All Christian educational and medical institutions were closed for a day across the state, and Sikh and Muslim leaders joined the sit-in.

“All these attacks stem from hate,” Father Donald D’Souza, spokesperson for the Catholic Diocese of Lucknow, tells mid-day. “There is no other reason for a law-abiding community in Mahim and elsewhere to be attacked. In the last 10 years, we saw sporadic attacks, but now they have become widespread and brutal. Something like this is unprecedented in Mumbai. The silence of authorities only emboldens the culprits.”

Apart from physical attack on its institutions and religious symbols, the community also feels vilified by accusations of religious conversion by force or lure. In November last year, the Union Home Ministry told the Supreme Court that the right to religion guaranteed under Article 25 of the Indian Constitution and the word ‘propagate’ used in it does not include religious conversion by force, coercion, allurement, deception, fraud and other means. Earlier that month, the apex court had observed that fraudulent religious conversion impacts the nation’s security, and had asked the central government to step in to take measures.

Although there is no central anti-conversion law, at least nine states have their own versions restricting forceful religious conversions. These include Odisha (1967), Madhya Pradesh (1968), Arunachal Pradesh (1978), Chhattisgarh (2000 and 2006), Gujarat (2003), Himachal Pradesh (2006 and 2019), Jharkhand (2017), Uttarakhand (2018) and Uttar Pradesh (2021).

Father Frazer Mascarenhas, parish priest of St Peter’s Church in Bandra West believes that “there is a major move to target first Muslims and now Christians, Dalits and tribal groups. This seems to be the policy of the establishment that is looking to build a rashtra for people of one faith. Although the Constitution promises equality, everyone else is subordinate [to the majority religion]. Absence of stringent action against the culprits is leading to an increase in such crimes.”

However, the Mahim incident, he says, can be attributed to someone who is mentally disturbed and incited by others. As for the Bandra West cemetery issue, which he spearheaded, Fr Mascarenhas says, “They did not gauge our sentiments about the graves when making amendments to the Development Plan for the road. For us, the cemetery is a place of worship.”

The accusations of conversion are a sore nerve. “Where is the evidence of any fraudulent or forceful conversion?” he retorts, “We are a vulnerable minority with no means to convert people. Without the slightest doubt, there is no en masse forced conversion. Isolated cases may crop up on all sides, but there is no proof against these claims.”

According to Census 2011’s data on Population of Religious Communities released in 2015, Christians make up for 2.3 per cent or 2.78 crore people in the country. The data further revealed that there had been “no significant change in the proportion of Christians” between 2001 and 2011.

However, a recent fact-finding report by Mumbai-based Centre for Study of Society and Secularism found that 1,000 Christian Adivasis were displaced from their villages after a series of violent attacks, and many of them were forced to convert to Hinduism. Led by director Irfan Engineer, the team visited villages in Chattisgarh’s Narayanpur and Kondagaon districts in December 2022.

“Why is a population that comprises just 2 per cent of the total population, targeted?” asks Fr Pinto. “To gain political mileage? There is no data to prove a conversion took place for financial gain. And if it did, it is absolutely wrong. My personal opinion is that if Article 25 includes the word ‘propagate’, which means to grow or spread, then conversion is undertaken by any religion. What else is the point? Would you advertise something, if you didn’t want it to be bought? If you hold election rallies and put up posters, don’t you want those to be converted into votes?”

Fr Mascarenhas points out the irony: “People are free to follow any religion of their choice, but conversion to a majority religion is termed ghar-waapsi.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!