For the first time in India, a physical and virtual exhibition unlocks a rich archive of documents, inspired projects, unbuilt works and rare photographs of one of Asia’s most influential architects

Dominic Sansoni, The Geoffrey Bawa Trust, c.1995

Towards the end of this interview with Shayari de Silva, she shares an anecdote about celebrated Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa’s interaction with Ahmedabad’s illustrious Sarabhai family. “The project was not built since Bawa was failing in health. We have [in our records] some correspondence, a few sketches, and a stack of photographs sent by the Sarabhais to entice Bawa to visit the site.” This detail about site visits is the underlining thought behind the title of the first-ever international retrospective of his work since 2004. Geoffrey Bawa: It is Essential to be There, currently on show at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), New Delhi, has been put together by de Silva, curator of the Geoffrey Bawa Art and Archival Collections.

Inspired by a statement made by Bawa (1919-2003) about the importance of an architect being on site, the title, she says corroborates the comments of colleagues and friends interviewed for Oral Histories, a section in the exhibition. “They described that his response to a new project would be to spend time on the site and envision what would come…we also see it in the archives, where Bawa frequently writes to clients, ‘My mind works only when I see the site…’”

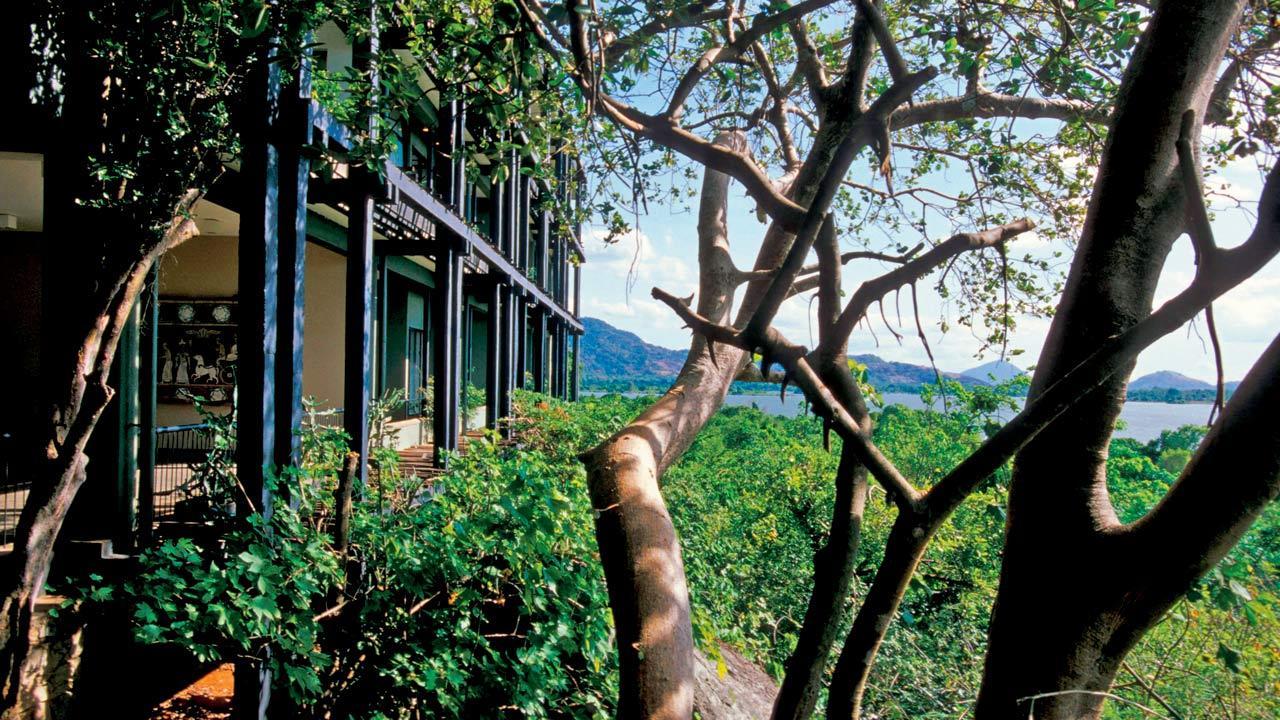

Kandalama Hotel, a luxury site, was a challenge to create given its location on a cliff facing the Sigiriya Rock. The rugged landscape and forested environs were complimented in the minimalist design. Pics Courtesy/The Geoffrey Bawa Art and Archival Collections

Kandalama Hotel, a luxury site, was a challenge to create given its location on a cliff facing the Sigiriya Rock. The rugged landscape and forested environs were complimented in the minimalist design. Pics Courtesy/The Geoffrey Bawa Art and Archival Collections

On till May 7, the exhibit that has both, a physical and virtual leg, has been organised under the aegis of the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, the High Commission of Sri Lanka, New Delhi and the Geoffrey Bawa Trust Colombo. Take the virtual walkthrough with de Silva guiding you across five decades of his work. Over 120 documents are on view, including a section of his unbuilt works and photographs from his travels.

Edited excerpts from the interview.

Why was it important to bring the exhibition to India?

Bawa’s practice was intertwined with India; he frequently visited [the country], and made important projects here. Indian audiences appreciate his approach and architecture to date. In this challenging moment in Sri Lanka’s history, the friendship and support extended by India to cultural endeavours such as that of the Geoffrey Bawa Trust has been invaluable.

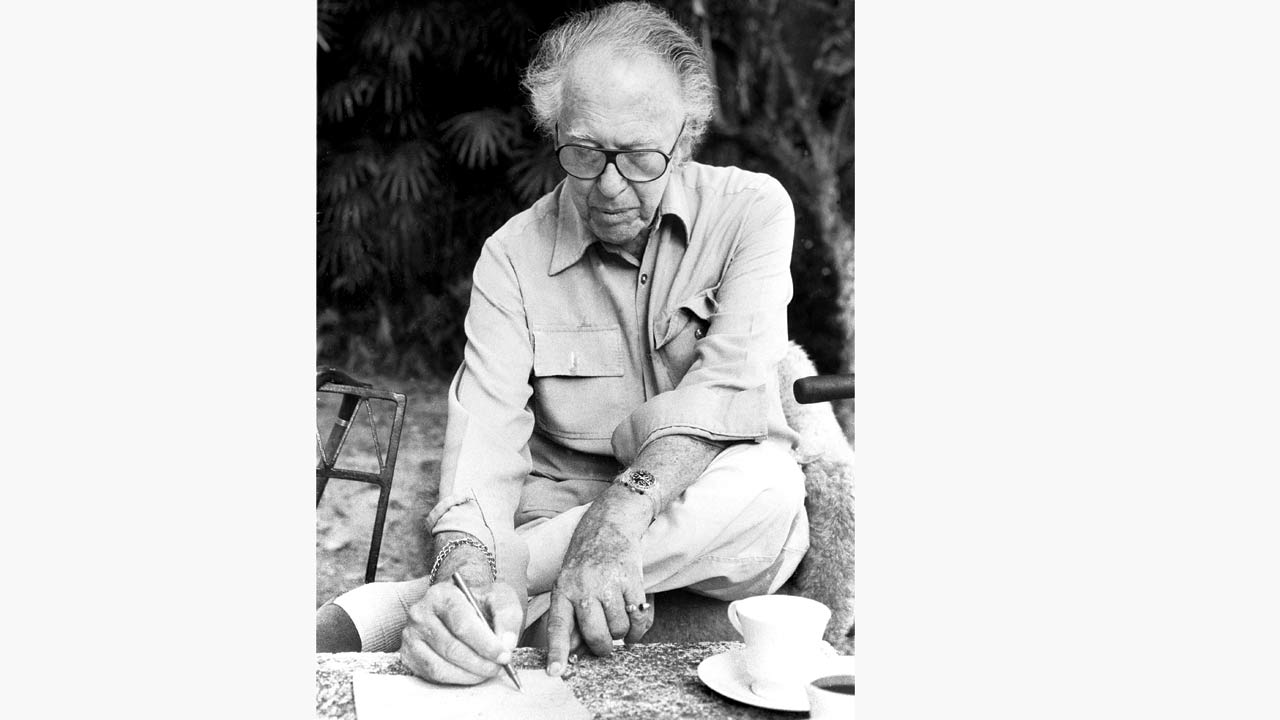

Geoffrey Bawa

Geoffrey Bawa

Bawa became an architect at 38, which is late…

He read literature at St Catherine’s College in Cambridge, and in his library at Lunuganga, we have his enormous collection of books from this time; works of fiction including novels, poetry, and drama. I wonder (and appreciate) what this literary background did for an architect like Bawa, and how it would have affected his appetite for narrative and choreography. He was a voracious reader across genres; he would often borrow books from friends and not return them! The other thing he did was to travel, and in his architecture you can trace the deft ways in which he was able to draw inspiration from places he had visited, and to transpose them in new sites and contexts.

Interestingly, he began working on Lunuganga [his country estate near Bentota River] as a 29-year-old, when he was technically a lawyer. The exhibition has a fascinating letter which Bawa wrote to his friend Jean Chamberlin on the process of finding the land on which the garden sits. It’s amazing that he was able to create a major earthwork at this early stage. And while it’s true that he officially qualified as an architect after creating the garden [his cousin suggested he pursue architecture so he could “do this with other people’s money”], maybe he was always an architect in a sense.

In 1948, Bawa’s architectural journey began with a purchase of a rubber estate near Bentota that he renamed Lunuganga. “The places where one might spend time have been thought out. Those experiences are complemented with a perfect view of the outside; it’s choreographed so that one is always in touch with the natural world outside,” says De Silva

In 1948, Bawa’s architectural journey began with a purchase of a rubber estate near Bentota that he renamed Lunuganga. “The places where one might spend time have been thought out. Those experiences are complemented with a perfect view of the outside; it’s choreographed so that one is always in touch with the natural world outside,” says De Silva

How did he design ‘bioclimatically appropriate’ buildings to address weather-related issues in the Subcontinent?

Bawa understood that architecture being climatically appropriate was fundamental; people often use the term ‘tropical modernism’ to describe his work, which I find to be problematic since it is such a colonised lens through which to view modernism. He designed projects for Italy, Brazil, and other countries, and in each, he sought to make what was appropriate for that particular culture and climate.

Also Read: Geoffrey Bawa's work at NGMA in Delhi

In Sri Lanka, this meant incorporating technological advancements enabled through the use of steel reinforcement while also seeking to create buildings that were naturally ventilated and kept out the heavy rains. So, his buildings from the late 1950s till the ’70s, reflect his use of pitched roofs, stacked floor plates overhanging those below for shelter and various mechanisms for enabling cross ventilation. The archive displays numerous attempts to use natural ventilation and explorations of how to open up the structure to enable this–finally settling on a monsoon window design that would continue to make the building an influential early example of bioclimatic design.

The Bentota Hotel was built in between two beaches and the Bentota River. It has drawn praise for using local influences from Sinhala and Buddhist architecture, and motifs including Ikat patterns in the lobby. Pic Courtesy/Cinnamon Hotels and Resorts, Sri Lanka

The Bentota Hotel was built in between two beaches and the Bentota River. It has drawn praise for using local influences from Sinhala and Buddhist architecture, and motifs including Ikat patterns in the lobby. Pic Courtesy/Cinnamon Hotels and Resorts, Sri Lanka

What can we learn about Bawa, the person?

He was a deeply private person, and didn’t preserve personal correspondence; even the documents of his professional practice were hardly retained. The letters and documents we have are largely from his friends and supporters, Jean Chamberlin and Christoph Bon, who thankfully, had the foresight to safeguard and subsequently donate this material to the Trust.

Shayari de Silva

Shayari de Silva

Did he ever discuss architecture or interact with Indian architects?

Charles Correa and [his wife] Monika were dear friends of Bawa and they travelled together extensively. He was deeply fond of both, especially Monika. We have a few of her textile works in our collection. She also took him to meet and purchase pieces from Ritten Mazumdar, which visitors to Lunuganga and Number 11 can see on view.

To explore the exhibit, log in to https://bawaexhibition.com/

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!