Covid cases may be negligible across India, but the Primary Health Centre staff at a tribal village in Nashik district is working the graveyard shift to vaccinate everyone

Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

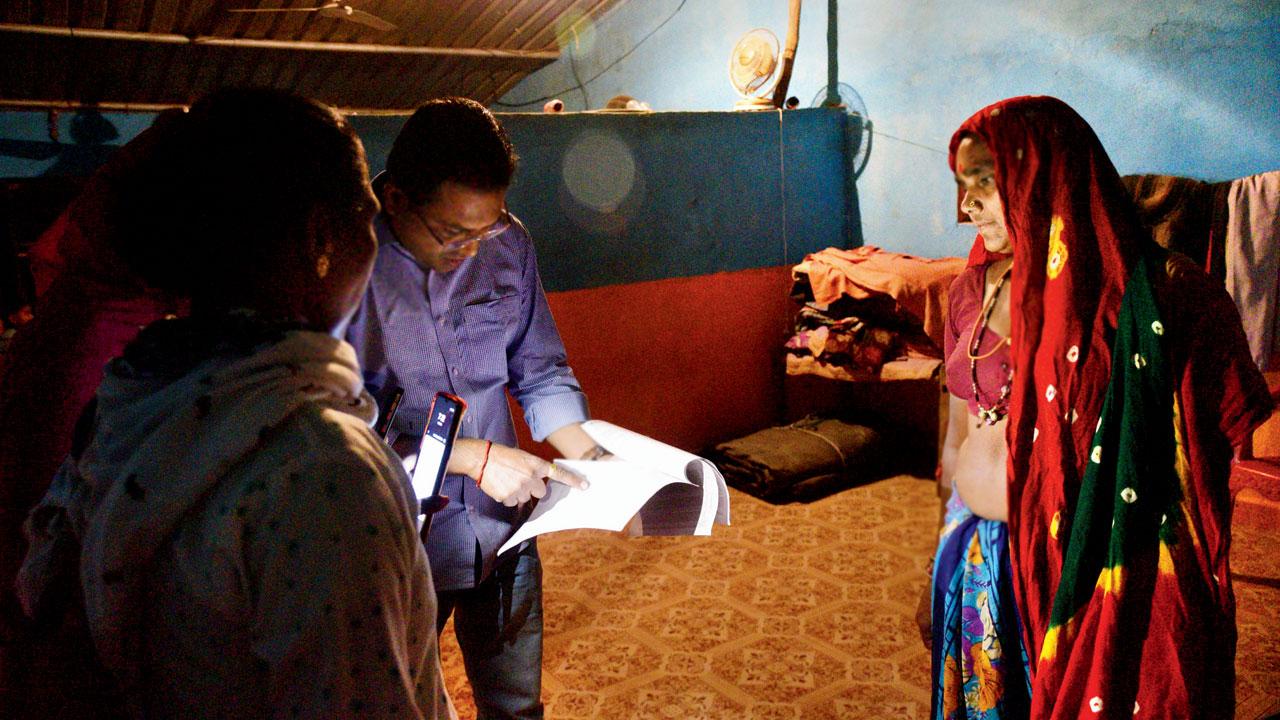

Caption: Nilabai Maalu Suryavanshi, a resident of Aliyabad, who was due for her second dose, was approached by health staff as part of the door-to-door night vaccination drive. While she initially complied, she refused and got up seconds before the nurse was to vaccinate her. Nilabai believes that her health deteriorated after taking the first dose.

ADVERTISEMENT

This is where time stands still. The village, situated in the Satana tehsil, previously known as Baglan, of Nashik district, is home to nearly 25,000 residents, a majority belonging to the Kokni tribe that inhabits parts of Maharashtra and Gujarat. It empties out before dawn, with farmers making a dash for their fields, and daily wage earners cramming inside pickup trucks, to travel across the border to neighbouring Gujarat 4 km away.

By 5 pm, when this writer arrives in the village after a 10-hour drive from Mumbai, Aliyabad has only just begun to return to life. Herders are heading back from the hills with their cows and goats, and women are seen gathering around hand pumps, steel handis in tow. The scent of sweat and toil is overrun by smoke from firewood burning inside homes. Cooking gas is a novelty. Houses still hold together only with bricks and mud. Electricity comes here as quickly as it goes. And only phones with one service provider’s SIM can promise network. It’s a world we’ve long forgotten.

Nilabai Maalu Suryavanshi, a resident of Bhimket pada in Aliyabad, is due for her second COVID dose. While she initially complied with health workers who visited her home during the night vaccination drive, she refused to take the shot when she saw a nurse approach her with the injection. Nilabai, who has difficulty walking, believes that her condition got worse after she took the first dose. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

Nilabai Maalu Suryavanshi, a resident of Bhimket pada in Aliyabad, is due for her second COVID dose. While she initially complied with health workers who visited her home during the night vaccination drive, she refused to take the shot when she saw a nurse approach her with the injection. Nilabai, who has difficulty walking, believes that her condition got worse after she took the first dose. Pics/Pradeep Dhivar

Undeveloped and remote as it is—the nearest city Satana, which is also the sub-district headquarter, is over 40 km away—the village, nestled in the Sahyadris, has left health officers in a quandary since the beginning of the Coronavirus outbreak in March 2020. Aliyabad, which is made up of nine gram panchayats and 27 padas, completely escaped the first wave of infection, with zero cases being reported. The subsequent waves, including the more recent and infectious Omicron third wave, saw a total of just 22 cases, and just one casualty, that of a senior citizen. Nashik district, where the village is located, reported an average of 318 cases per day last month.

It’s a tiny victory for the Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) staff, and one would imagine, a good enough reason to give themselves a pat on the back. But, when we visit, the staff at the PHC is experiencing the very opposite of that. “Everybody here knows about Corona, but because there were hardly any cases, nobody believes it to be dangerous. It’s like any ordinary cold for them,” says Dr Manisha Rajaram Mohite, medical health officer at the Aliyabad PHC. “Which is why most of the locals have refused to take the vaccine. They think we are injecting something that will in fact, make them sick.”

Kamal Choudhary, an ASHA worker, in Hanumant pada, who has been trying to convince villagers to get vaccinated, says that she often gets booed away. “They get violent and even throw stones at us”

Kamal Choudhary, an ASHA worker, in Hanumant pada, who has been trying to convince villagers to get vaccinated, says that she often gets booed away. “They get violent and even throw stones at us”

The issue came to a head in October 2020—10 months after the vaccination drive had kick-started in the country—when health officials had barely vaccinated 50 per cent of the 18,322 villagers, eligible for the dose. “We were desperately trying to find a way to convince them to take the vaccine,” remembers Dr Mohite. It’s around this time that the Taluka Health Office in Satana, which had been given the target of 95 per cent vax coverage, came up with the idea of a door-to-door vaccination camp that would kick off after sundown. The drive, which begins daily at dusk and sometimes continues until midnight, has met with successful results. In the last four months, health officials claim to have covered 70 per cent of the targeted population in the village.

The Kokni is a scheduled tribe residing in the Sahyadri-Satpura ranges of Maharashtra—mostly in the Nashik, Nandurbar and Dhule districts. They are also distributed in the Valsad and Dang districts of Gujarat. Most of the community members are agriculturists, but the landless Kokni members still work as farm labour. “In Aliyabad, the tribals leave for work by 6 am, and only return late in the evening. When we first began the drive last year, we’d give them the vaccine at the PHC during the day, at around 8.30 am. Though the vaccine was free, they had to take a day off from work to visit the centre. They couldn’t afford losing the wages. This deterred many,” remembers Dr Mohite, who has been working at the Aliyabad PHC for the last three years. An early morning drive also failed. The elderly population, she says, was most difficult to convince. “Most of them are uneducated and believe in superstitious practices. They don’t even come to us to get treated for a snake bite. They’d rather go to the babas and bhagats,” she says, “When we told them about how the vaccine would create antibodies that would help fight COVID-19, most of them didn’t seem to care. They said their time was already up anyway.”

Health staff from Satana city, 40 km away, arrive in a COVID ambulance to vaccinate tribal residents of Aliyabad

Health staff from Satana city, 40 km away, arrive in a COVID ambulance to vaccinate tribal residents of Aliyabad

Such an environment, she admits, wasn’t conducive to create awareness about a disease that had barely hit home. “When the pandemic broke out, we had tried to spread awareness about using masks and sanitising regularly. In fact, we wouldn’t allow villagers to visit the PHC without masks, but they simply refused to listen. They couldn’t understand why we were making such a big deal about Corona.” The PHC on its part was COVID-ready, conducting regular RT-PCR and Rapid Antigen Tests at their laboratory. Though cases were few and far between, COVID positive patients were sent to a nearby isolation centre, which again prevented suspicious locals from reporting their symptoms.

In order to boost the vaccination drive, the PHC staff enlisted the help of local Zilla Parishad officials, the sarpanchs as well as the police patils to reach out to locals. “We would organise camps every single day, even on weekends, but got no response. It was quite disappointing,” she shares. By October 2020, the staff had barely vaccinated 10,000 people. Kiran Shewale, taluka health supervisor at the Taluka Health Office, Satana, says that Aliyabad was the worst performing village in their tehsil. “We knew that we had to pull up our socks.”

Nitin Prakash Sarak, a local health worker, checks the list of vaccinated patients due for the second dose

Nitin Prakash Sarak, a local health worker, checks the list of vaccinated patients due for the second dose

Around this time, several rural pockets in Maharashtra had already begun conducting night vaccination camps. In villages in Dhule district, for instance, health officials with the help of local ASHA and Anganwadi workers would organise weekly night camps at makeshift centres and halls in the village premises for daily wage earners. The Satana health staff decided they’d also give it a shot.

The COVID ambulance that mid-day’s vehicle followed from Satana reached the village around 5 pm. It takes around one-and-a-half hours to reach Aliyabad from the city—for most part, the ride is bumpy and uncomfortable with no street lights on the way—but health workers have been travelling to and fro daily. The staff has already vaccinated 12,983 villagers in the area, with at least one dose. While 6,250 residents are awaiting the second dose, 5,339 eligible locals are yet to get vaccinated.

Kiran Shewale, taluka health supervisor at the Taluka Health Office, Satana, says that they had to undertake the night vaccination drive in Aliyabad, as it was one of the worst performing villages in their tehsil in terms of vaccine coverage

Kiran Shewale, taluka health supervisor at the Taluka Health Office, Satana, says that they had to undertake the night vaccination drive in Aliyabad, as it was one of the worst performing villages in their tehsil in terms of vaccine coverage

Shewale, who has been monitoring the drive, has joined us from Satana. “Most of the villagers have no knowledge about vaccines. They don’t remember when they took their last dose, and whether it was Covaxin or Covishield. Some don’t even have mobile phones and if they do, they can’t register themselves. So, we have to do it for them on our phones. We struggle with this too, as the network is terrible in this part of Maharashtra,” says Shewale. He admits that it can get difficult for them to keep tab of eligible candidates. “To circumvent this problem, we started giving them a token, where we’d mention the date of the first dose, the vaccine that they took and when they are due next. Very often, they’d lose that token too.”

Now, ASHA and health workers keep a list with them; those who are due for the vaccine are usually approached by the team leading the night vaccination drive. The first pada we visit, Hanumant, has seen one of the lowest turnouts in the region. While 587 have taken their first dose, only 266 locals have taken both shots. Kamal Choudhary, an ASHA worker, says that she has been booed away by residents one time too many. “When they see us, they shut the door. Sometimes, they get violent and hurl stones at us. But, this is our job and the government has given us a target, so we have to do our best,” she says. She is, however, hopeful that they’ll be able to cover more ground, when some of the migrant labourers, currently working in the sugarcane fields in Pune, as well as UP and Bihar return to celebrate the Holi festival this month.

Dr Manisha Rajaram Mohite, medical health officer, Aliyabad PHC

Dr Manisha Rajaram Mohite, medical health officer, Aliyabad PHC

When we meet the sarpanch, Kalu Somnath Choudhary, he refuses to admit that villagers don’t take the vaccine. “They don’t have a choice, they need to take it,” he says. “I’ll ensure that,” he assures the ASHA worker we are accompanying. Later, he tells this writer that villagers are wary because during the second wave, when someone would show the slightest of symptoms, they’d be taken in an ambulance and kept in the isolation centre. “It was a precautionary measure, but now they are scared.”

In Bhimket pada, which is a 10-minute drive from Hanumant, locals are more forthcoming. An impressive 922 villagers have taken their first dose, and 280 have taken both. But, the scepticism continues. When the health workers visit the home of Nilabai Maalu Suryavanshi, who is due for her second dose, she complies and sits down to get the shot. But as soon as the nurse approaches her with the syringe, she gets up and steps away. “I don’t want it,” she says. “Please go.” When we ask her why she won’t take the vaccine, she says that she has had a problem with walking for a while, and had stopped going to the fields. “After I took the first dose, my condition worsened. Now, I need to drag myself. If I take it again, I won’t be able to get up at all.” Shewale says that it’s hard to counter this kind of misinformation. “Now, when people develop a slight fever, they blame it on the vaccine. Rumour spreads fast here. They don’t believe in science, so how are we going to tell them that they are misguided?”

Reshma Shantaram Sable, who supervises over 15 ASHA workers in the region, says vaccine hesitancy is rife within the community. “We may have managed to get them to take the first dose, but many have refused to take the second.” Sable says that several ASHA workers have been assaulted. “When they get too violent, we ask the police patil to accompany us. It’s a risky job for the women.”

Nitin Prakash Sarak, a local health worker, says they cannot use extreme measures to convince villagers to take the vaccine. “When authorities across the Gujarat border did not allow non-vaccinated labourers to travel there, some of them took the vaccine. There has been no outbreak here, so their scepticism is justified. Our job is to let them know this is safe for them, and it’s for their own good. We have to be very patient.”

24,935/22

Total population of Aliyabad versus the number of COVID cases reported here since 2020

Why Aliyabad stayed safe

According to Dr Manisha Rajaram Mohite, medical health officer at the Aliyabad PHC, the village is situated in the remotest part of the region, and hence, didn’t see cases during the first wave, when the Centre had declared complete lockdown. “Villagers are self-sufficient and do not have to travel long distances; they consume what they produce. Because they eat organic, healthy food, they also have good immunity.” She says that testing continued at the PHC during the three waves, and patients with symptoms were isolated.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!