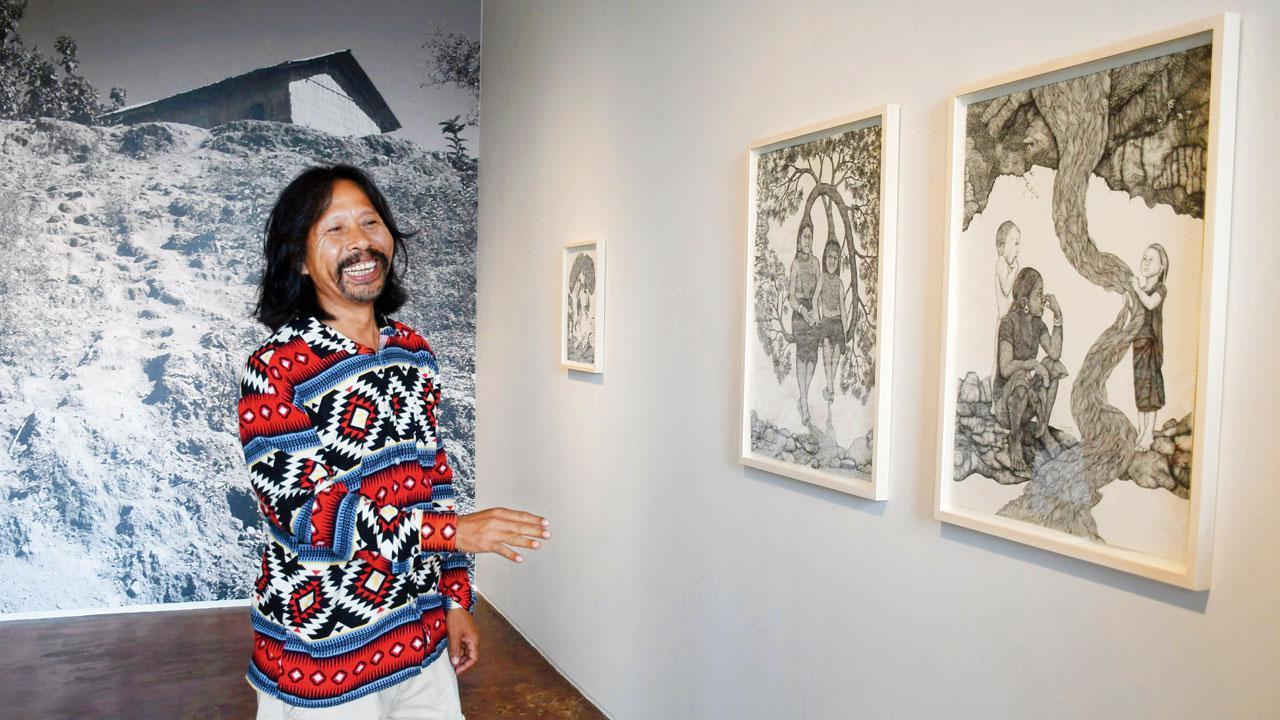

Joydeb Roaja—one of the Jumma people of Bangladesh—mirrors the history and struggles of his community to hold onto culture and land

Joydeb Roaja

When Joydeb Roaja was a student, he struggled with the Bengali curriculum at school. “As a Tripura indigenous person, my primary education was not good because my mother tongue is Kokborok, but the textbooks were in Bangla. To add to this, the teachers spoke a completely different language, so I didn’t understand anything!”

ADVERTISEMENT

he recalls, when tracing his roots as an artist. While he could not understand the study material, he was fascinated by the illustrations of Bangladeshi painter Hashem Khan, which adorned his school books depicting stories of rural life in Bangladesh.

Till then, most artists and writers romanticised the nature-entangled lives of the Jumma people—a minority tribal group in the Chittagong Hill Tracts region of Bangladesh. Roaja wanted to paint the violent struggle necessary to maintain the Jumma way of life, which often went against military occupation. “At the time, the different indigenous people, including the Jumma, started an armed struggle to demand autonomy, which resulted in having to hide and live in the forest. Most of my artwork is influenced by this devastation I witnessed as a child,” he laments.

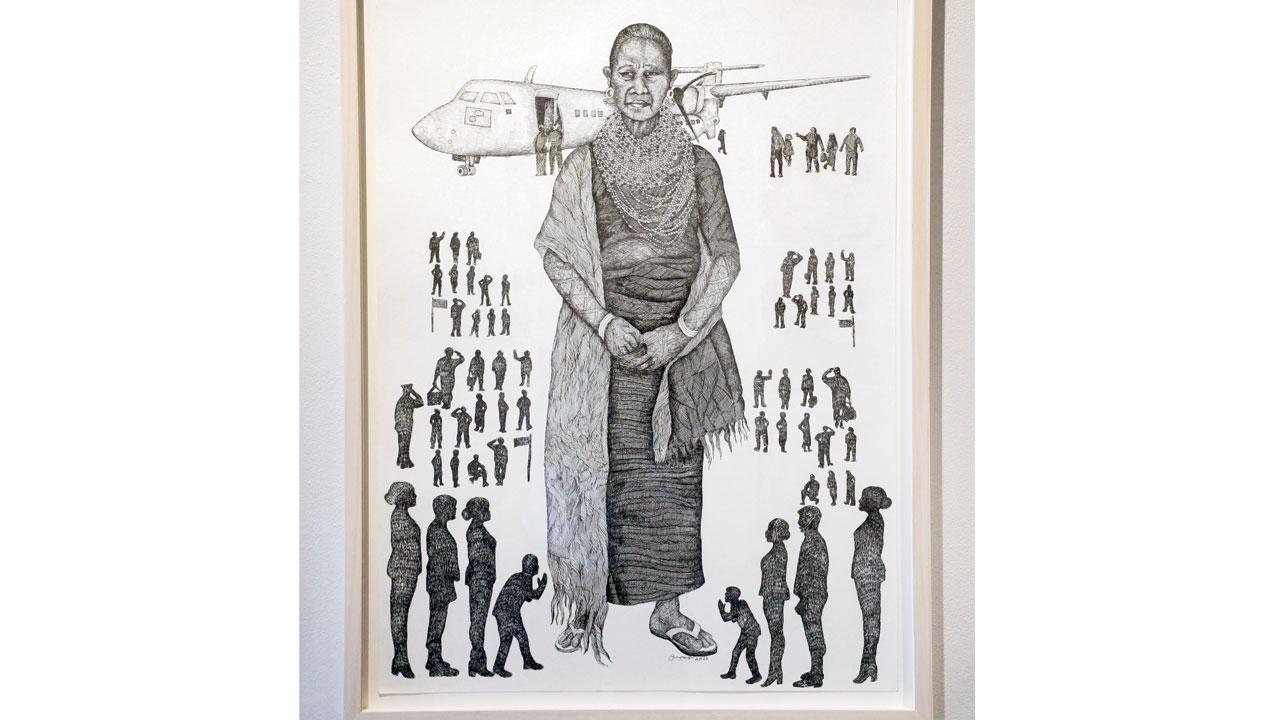

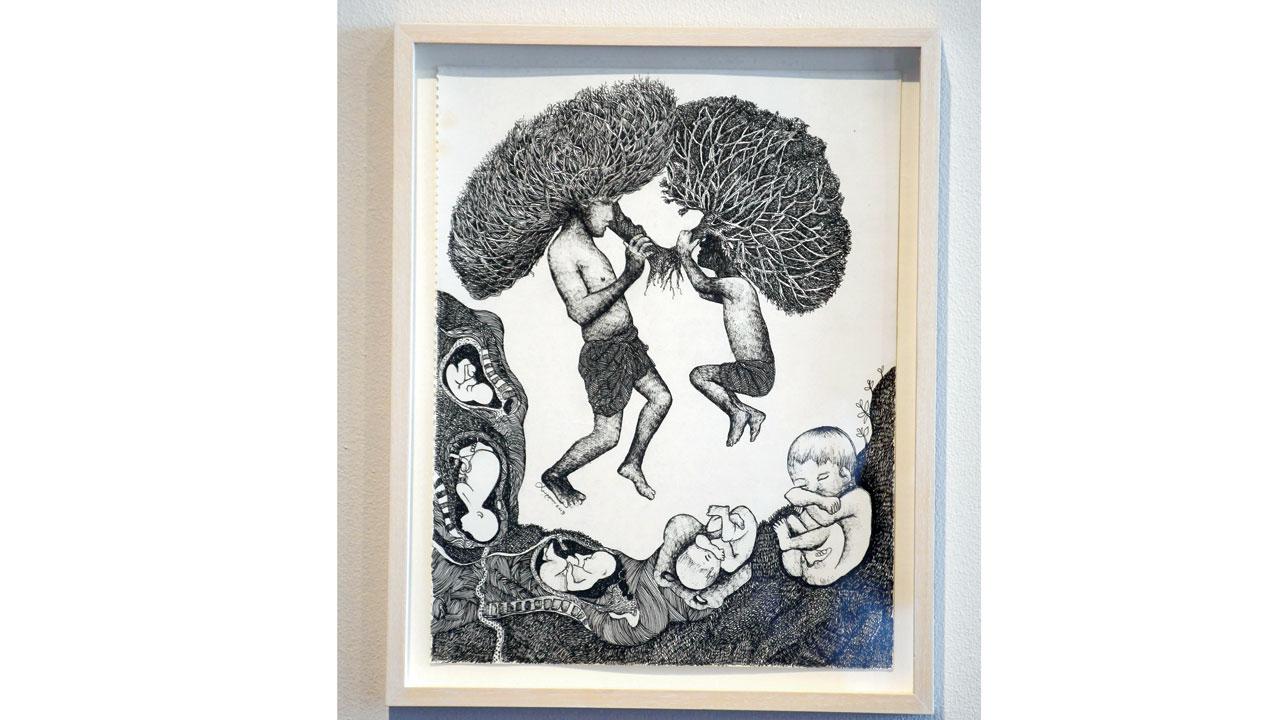

In an ongoing exhibition, we get to delve into his life’s experiences expressed through a series of monochrome ink drawings of his community, which opens a window for the viewer to visualise the crises they face. In Generation Wish Yielding Trees and Atomic Tree, we see social and political power roles and struggles given a utopian reversal. Without any background art or motifs betraying the location or physical topography of what is being portrayed, an exaggerated juxtaposition of resized people immediately symbolises and draws the eye to a shift in dynamics. We see minuscule-sized corporates and military figures bowing to or submissively placed against the Jumma people, drawn in their traditional garb and ornaments with motifs of their shifting slash-and-burn form of agriculture (known as jhum farming) appearing as a common thread in each work.

A similar theme runs through another series titled Right to Relief. “During the pandemic, I stumbled upon images of relief distribution in Bangladesh on Facebook. The people receiving relief seemed embarrassed and helpless, while those [doling it out] wore smiles of triumph. There was an image where one person received a single sack of rice from multiple relief givers, who were broadly smiling at the camera. The receiver was desperately trying to hide his face in shame and humiliation. I would like to envision a future where there’s dignity in seeking relief, and not a show of power,” he says. Another series of seven ink sketches titled Go Back to Roots opens a lens into a more humble world, the Jumma way of life.

He works primarily in performance, installation and drawing, often finding inspiration and materials among the area’s tribal cultures and natural hilly landscape. Human bodies blend seamlessly into branches, leaves and roots to create visions of interconnectedness and resilience. Pics/Ashish Raje

Roaja explains the political dynamics between 11 different indigenous people living in the region between the three hill districts of the Chittagong Hill Tracts. “To protect the land and culture, a tribal organisation called Shanti Bahini was formed, which led to armed conflict between them and the Bangladesh Army. I spent my childhood in a horrible state of war. Living in a village in a remote hilly area, I didn’t get a chance to play football or cricket—we played war games. Also, one of the most unpleasant experiences I had as a child was when the army would surround and search our house on winter nights. They would force every family member to line up in the yard, while they ransacked the house. Each time, they would put a gun to my father’s head and warn him against giving shelter or food to Shanti Bahini. As a result, I always felt like I had a heavy weapon against my head. I don’t create art based on politics; It’s a presentation of events that happened from my childhood to now, and a

hope that the government and army will respect the persecuted indigenous people in the future.”

Roaja’s early drawings were sketched secretly, rolled up and hidden in bamboo sticks in a corner of his house. He recalls one of his teachers viewing his work and telling him he’s very talented, but warning him about getting into trouble should anyone else see it. Out of fear, he destroyed each and every one of them. Today, he also recreates his art and message through impromptu performances at each exhibit. While most of these enactments are an extension of his work, they’re often not planned with a fixed direction. “I usually go with what I’m feeling in that moment—the ideas come to me along the way.”

WHAT: Joydeb Roaja’s solo exhibition

WHEN: Till August 20, Tuesday to Saturday from 11 AM to 6.30 PM

WHERE: Jhaveri Contemporary, third floor, Devidas Mansion, Apollo Bandar, Colaba

CALL: 22021051

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!