After a Netflix film used axone to talk about politics of food and identity, we decided to decode the fermented soya bean with help from the people who know it best

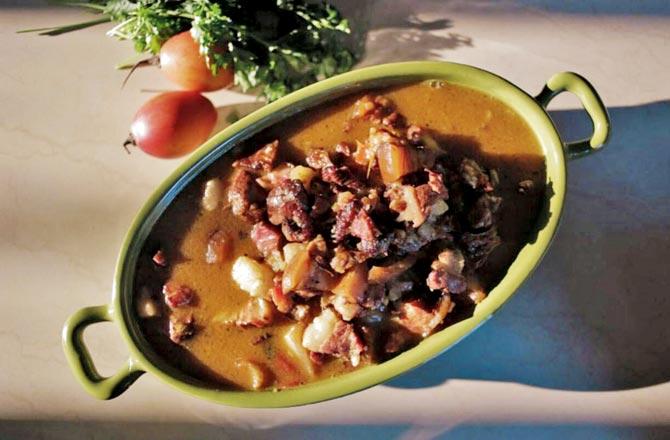

Pork in axone with bamboo shoots and bhut jolokia is one of the highest selling dishes at chef Alistair Lethorn's pop-ups

In the opening sequence of Axone, a film by Nicholas Kharkongor currently streaming on Netflix, Upasana (Sayani Gupta), Chanbi (Lin Laishram) and Zorem (Tenzin Dalha) smuggle axone, a fermented soya bean paste into a room on the terrace. Set in Humayunpur, South Delhi, the plot revolves around the challenges faced by the flatmates from Manipur and Nepal, who wish to surprise a friend, from Arunachal Pradesh, by making her favourite dish. Pronounced 'akhuni', the condiment is known to have an overpowering aroma and is eaten as chutney, in curry, or with smoked meat and fish.

ADVERTISEMENT

Smoked pork in axone

As he watched the movie, Delhi resident Tituraj Kashyap Das, originally from Guwahati, was reminded of his own experiments with the ingredient when he was a student at Pune University. "Back then, I had friends from Nagaland, and one of them decided to make a pork dish using axone. While in the midst of it, we got a call from the landlord complaining about the strong smell," he says. No amount of flak has deterred Das, now a public relations executive with a chain of hospitals, from cooking with it. A self-confessed foodie, he and wife Rupamudra Kataki, often stack the ingredient—dried, wet, semi-dry—in their kitchen. They have scoured the neighbourhood and built connections in the capital, with chefs and students who make frequent trips back home, to ensure that they don't run out of stock. But the lockdown is proving to be a rather long, dry spell. "One might assume that just because I'm from the Northeast, I'm familiar with the ingredient, but that's not the case," says Das, 39. "Axone is dominant in Nagaland and Manipur, not so much in Assam. In fact, I sampled it for the first time at a Guwahati restaurant and was struck by its unique flavour." He admits that it's an acquired taste. It's only after you experiment with it that you begin to discover its versatility.

Plain boiled rice, dal (without tadka), boiled vegetables, pork cooked in bamboo shoot and bhut jolokia and axone chutney made by Tituraj Kashyap Das

According to the website of the Tribal Cultural Heritage in India Foundation, Nagaland has 16 different tribes, each with one or more dialects, and Tripura about 20 tribes.

Tituraj Kashyap Das with wife Rupamudra Kataki

Although a staple delicacy of the Sumi tribe of Nagaland, the condiment has travelled to other parts of the country, including Mumbai. Hoi Liethang, who works as a teacher at the International Society of Fashion Technology in the city, sources axone from select shops in Kalina. "Every time I visit Manipur, I bring some with me. It's comfort food," she says. There are two ways of making axone: either dry or paste-like. "We soak soya beans overnight, boil them in water till they become soft. Then, the water is drained and the soya beans are put in bamboo baskets lined with banana leaves. This is then kept over a fireplace in the kitchen for fermentation to start. In cities, we keep it in direct sunlight." Although it's the dehydrated form that she brings home, Liethang prefers the paste for its potency.

The word axone comes from the Sumi dialect and is prepared all year round from soya beans by the Sumi Naga tribe of Nagaland

Chef Alistair Lethorn who runs Aal's Kitchen, from his Madh Island pad, explains that every tribe has its own timeline of fermentation and that makes a difference to the flavour profile. "The Manipuris take it out of the fermentation process much faster than the Nagas. The smell is more prominent in the early stages of fermentation." His patrons, however, have taken to it with alacrity. The smoked pork in axone is one of his highest selling dishes.

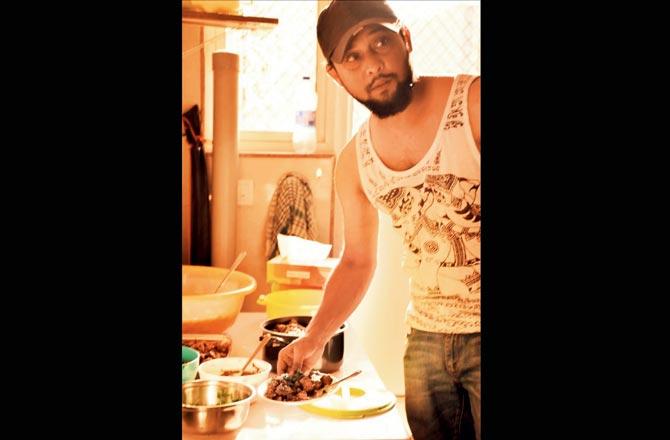

Chef Alistair Lethorn

Traditions of preservation and fermentation are key to the Naga way of life, says executive chef-partner Thomas Zacharias of Lower Parel resto-bar The Bombay Canteen. He dedicated a detailed Instagram post to axone during his Chef on the Roadtrip series to Nagaland, in 2018. "The Nagas use axone in a variety of chutneys, pickles and stews, and most notably, in the incredibly flavoursome smoked pork," he says. At the Angami home in Khonoma, an organic village, Zacharias witnessed it being added to yam stem and wild basil curry. "It was a simple unassuming stew, but a dash of axone was enough to elevate the taste and lend it a complexity." Because it's a strong flavouring agent, Lethorn suggests it be used wisely and sparingly.

Chef Zacharias holds a pack of axone paste. He says Nagas ferment close to 150 different types of products, each with its own flavours and nutritional benefits

Dolly Kikon is a senior lecturer in the anthropology and development studies programme at the University of Melbourne. She is currently completing a book project on fermenting food cultures among Himalayan societies. A native of Nagaland, Kikon says for Himalayan cultures, fermenting is a journey of preserving food and exploring taste. Among all the food items that Naga people relish, axone occupies a distinct place. "It is made in everyone's home; there is no mass production in Nagaland. So we can say it is artisanal and a specialised item." But when it comes to fermentation, there is a procedure. "Although it appears as a straightforward process, the fermenter is aware of the complexities involved. From seasons, rain, sunshine, and moisture in the air to moods, the story of fermenting food is rich and magical."

Thomas Zacharias during his Chef on the Roadtrip series to Nagaland, in 2018

It's what inspired her to delve deep into the local food practices and the tradition of fermentation. "Although the nutritional values and rich heritage of fermented food across Himalayan societies are well known, it was not until I realised that the Northeast's fermenting culture needs celebrating did I start working on a book project." She believes that understanding the place of fermented food in Naga society will give us an insight into people's relationship with the land and their interconnectedness. "Adopting a fermenting culture means being intimately linked to sustainability and taking care of the earth, where we value the role of microbes and generate greater awareness about our food."

Dolly Kikon, lecturer, anthropology and development studies programme at University of Melbourne

She feels it's important that it is made part of public discourse. "In Indian metros, residents from the Northeast face discrimination, including food shaming. Landlords are known not to rent their home to those who eat 'smelly food'. I feel we need to talk about fermented food, taste, caste practices and discrimination in contemporary India." Zacharias says for the average Indian, Northeastern food equals momos. "Nobody in the Northeast of India traditionally makes momos. The only parts where you find it, like Sikkim, is where migrant Tibetans reside."

Talking about its "smelly" aspect, Kikon underlines how these olfactory reactions are created by humans themselves. "Masala is smelly, cheese is smelly, sambar is smelly. What I mean is aroma is integral to all food cultures. If a dish of fermented bamboo shoot is tasty for me and invokes memories of home, does it give another the legitimacy to suggest otherwise? Food habits are deeply political in India. But should I be apologetic of my habits? Whose sensibilities am I trying to align with? When we loosely use the term 'Indian food' are we including tribal culinary traditions, for instance?"

Other fermented foods

. Fermented bamboo shoots: According to the Slow Food Foundation for biodiversity, its juice has preservative property similar to vinegar and so meat, fish or vegetables cooked with it have longer shelf life.

. Anishi: It's a Naga delicacy of fermented leaves made into patties and smoked over the fire or sun-dried. Anishi is prepared from the leaves of the edible Colocasia genus.

. Tungrumbai: A Khasi delicacy from Meghalaya, it is consumed as a side dish with rice.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and a complete guide from food to things to do and events across Mumbai. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates.

Mid-Day is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@middayinfomedialtd) and stay updated with the latest news

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!