And, its history dates back to the 12th century if not earlier — Ronojoy Sen, author of new book on the subject, will tell you

football

ADVERTISEMENT

India, “they” say, lacks a sporting culture. Discuss this with Ronojoy Sen and he will tell you that Sanskrit manuals have records that date wrestling back to the 12th century. His other favourite nugget is how India gifted Britain (and therefore, the West), it’s favourite elite sport, polo.

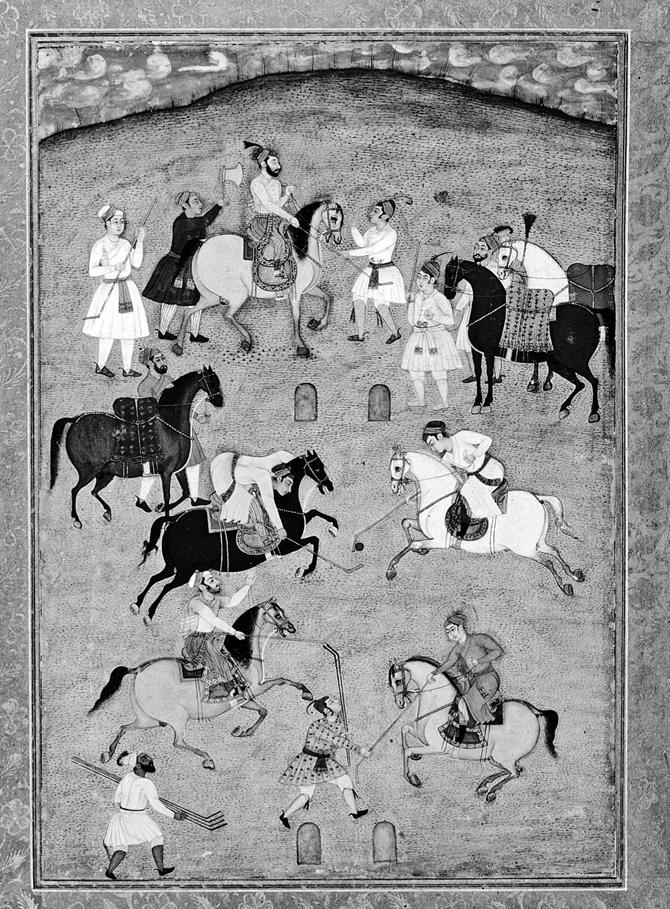

It’s a development, the 46-year-old, calls counter-intuitive. Sen, who has authored Nation At Play — A History of Sport in India (published by Penguin Books India), says records show the sport being played, albeit in a different version than what we know it, in the Mughal court. In fact, he writes, the country’s first Muslim ruler, Qutubudin Aibak is believed to have died during a polo game when he was crushed by his horse. But it was during Akbar’s time that the sport gained popularity.

A Mughal painting of a polo match from the 17th century. PIC/COURTESY VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM, LONDON

In fact, says Sen, who is a senior research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies and South Asian Studies Programme at the National University of Singapore, Abul Fazl, Akbar’s chronicler, describes how the game was played and that there were 10 players on each side.

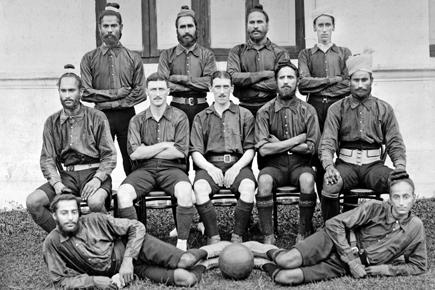

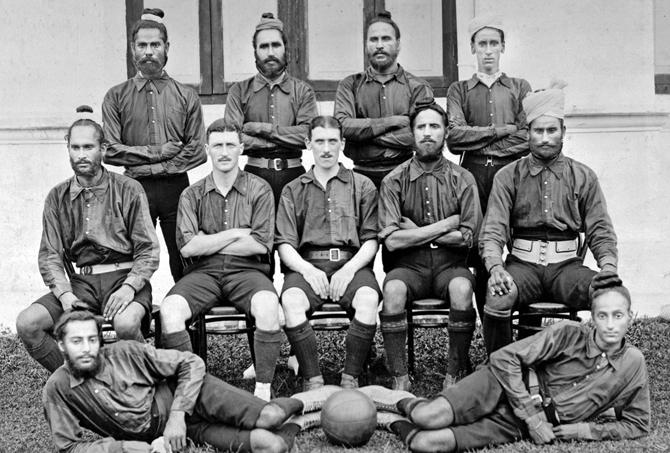

A photograph of the football team of the Twentieth Duke of Cambridge’s Infantry, 1920, provided to Sen. Of 11 players, only two are British. PIC/COURTESY COUNCIL OF THE NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM, LONDON

A photograph of the football team of the Twentieth Duke of Cambridge’s Infantry, 1920, provided to Sen. Of 11 players, only two are British. PIC/COURTESY COUNCIL OF THE NATIONAL ARMY MUSEUM, LONDON

“When the ball was driven to the end of the ground, loud drumbeats announced the event,” Sen writes. Yet, he says over the phone from Singapore, polo was picked up by the British not from the Mughals, but from the Manipuris. “Whether the Manipuris adopted it from the Mughals, I don’t know, but in the 1850s, British soldier Lieutenant Joseph Ford Sherer observed tea plantation workers in Manipur playing the game.

However, when the transition happened, the rules changed,” he says. There are seven players on each side in Manipuri polo compared to four in Western polo. There are no goal posts in the first, and a goal is scored when the ball crosses the terminal line on the opposite of the field. All players in Manipuri polo must wear a white dhoti without border, turban and a coloured jacket, he says.

Ronojoy Sen

The other sport that intrigued Sen, who spent three years and scoured a dozen libraries for material, is wrestling. Its history in India dates back to at least the medieval period with texts like the Manasollasa (12th century) and the Mallapurana (15th-17th century) discussing rules, grades of wrestlers and awards given to them — interestingly, there are records by Portuguese traveller Fernao Nuniz from Vijaynagar during Krishnadeva's reign where the loser of the wrestling match was rewarded — and even their regimen. What the modern-day fan of wrestling might find familiar is the aggression. In the asura form, Sen writes, “injury to ear and nose, falling of teeth, biting, pulling of hair, throwing earth, scratching with nails, breaking fingers etc” was permitted.

Yet, it’s not the violence of the sport that Sen finds intriguing. “It is the phenomenon of the Indian wrestler going out of the country, as early as the 1900s, to participate in professional matches.”

It’s not just Gama (the wrestling star from Madhya Pradesh who was in the employ of several princes), but others as well. “There was Gobor Guha, who was from a wealthy Bengali family and made his way to America to fight bouts in Oklahoma and Tulsa in the 1920s,” Sen says. Guha makes an interesting mention, says Sen, because he reflects the physical culture of the Bengali elite who had taken up sports as a daily regimen. “Guha’s akhara in Bengal still stands. But, part of it now functions as a gym,” he says.

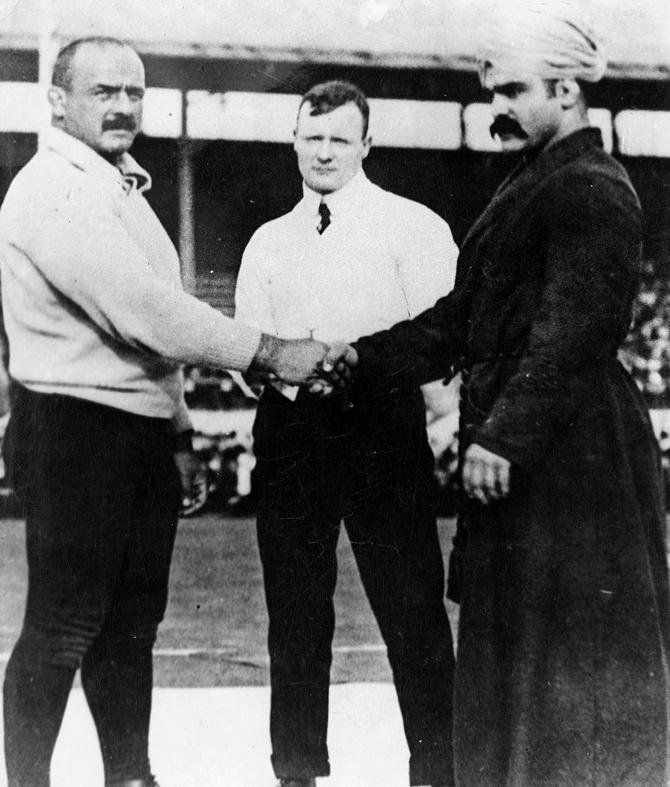

Gama (right) and Portuguese wrestler Zbyszko before their bout in Patiala, 1928. The bout ended in Gama's victory in less than a minute. PIC/COURTESY H J LUTCHER STARK CENTRE FOR PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORTS, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN

As a Bengali, it would have been amiss of Sen not to trace India’s football journey. He does. Even identifying the man considered possibly the first Indian recorded to have ever kicked a football: Nagendra Prasad Sarbadhikari. Nagendra, legend has it, stopped to view British soldiers playing a game with a round ball at the Calcutta FC ground. While the ball bounced towards him, one of the soldiers asked him to “kick it back”. That Nagendra later went to found several football clubs in the city is why he is often considered the father of the sport in the country.

While such information has been documented by various authors, what prompted Sen to write this book, was to allow a comprehensive history of the evolution of sports in the country, i.e. of a sport beyond cricket.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!