Embroiderers Istiaq and Ashfaq Shaikh can create alchemy with polyester threads. Textile artist Loise Braganza showed them how to create art

Embroiderers Ashfaq and Istiaq Shaikh at their workshop. Pics/Sameer Markande

Istiaq and Ashfaq Shaikh are above-average embroiderers and below-average salesmen. When we meet in their workshop in Bandra East, the brothers are working on an elaborate landscape, like an ambitious Anchor stitch kit, with a vacation home set against an English countryside.

ADVERTISEMENT

They're creating every surface with a different stitch: the grass is in long, wavy strands; the leaves in tight Afro curls; the meadows in braided ribbons of green and gold. A private commission, they've been on it since a fortnight. "Sukoon ka kaam hai," says Istiaq. "Because you have to think of every minute thing before you do it." We ask the ballpark figure for an artwork like this, and our mental math suggests a lakh. Ashfaq says, "We'll charge more than Rs 20,000."

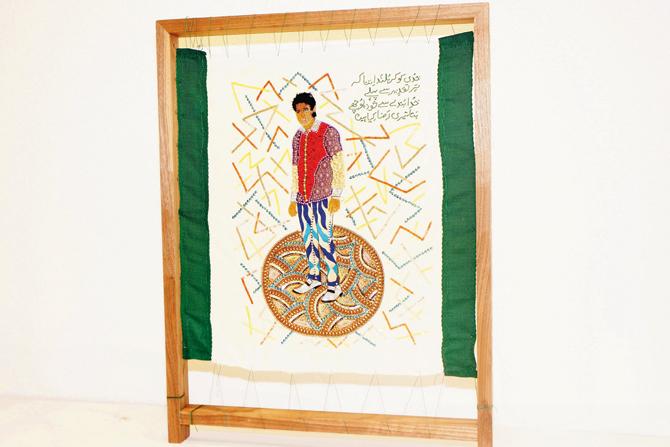

Embroidered self-portrait of Istiaq Shaikh. Pic Courtesy/Anne van Beers

When we start doling out unsolicited financial advice, Istiaq says, "We understand the value of our work, but the middlemen take all the money in our trade. The boutique owners keep the lion's share. If there is a Rs 50,000 piece, they'll keep Rs 30,000. If we ask for more, they tell us, 'Let it be. Someone else will make it.'

They don't even pay us on time. It wasn't like this earlier. In our daddy's time, madams used to come home and say, 'Bhaiyya, please do our work. We'll give more money.' Haath-pair jod ke jaate the. Now it's the opposite. We have to say, 'Madam, please give us work.'" An embroiderer is a skilled craftsman who can create whole worlds with threads of gossamer. But, in our country, he's been rendered voiceless. In 2017, textile artist Loise Braganza set out to change that.

Loise Braganza

A former stylist and costume designer who retreated to academia, Braganza was doing her master's at ArtEZ University of the Arts in Arnhem, the Netherlands, when she chose to do her thesis on embroidery in India. "My course was on fashion theory and asking questions like: what making is, why do we design, what is it in relation to the body and to other collaborators?" Following that thread of thought, she landed at the Shaikhs' karkhana, and shadowed them for a month. "It is a very tedious skill: positioning the needle, holding the needle and pulling the thread between the needle into a thin wire, which is less than a millimetre, and [spearing] this wire on to the fabric. It takes a lot of skill to do that. It doesn't come out of just one day of work."

The Shaikhs are old hands at their handiwork. Istiaq, 34, and Ashfaq, 31, have bent their backs over unadorned fabric since they were 10 years old. "Our daddy used to make us work for 14 hours," says Istiaq, breaking the news with a smile. "We used to feel like playing outside, but there were financial issues at home, so we had to work." Their earliest lessons were removing takas (threads), a little zari work and doing outlines. "Slowly we picked up the other skills, as work started pouring in."

Braganza got in touch with them because she knew "they were more willing [than most embroiderers] to try something new." Though, they still had to iron out a few differences. She says, "In the beginning it was all about, 'You tell us what to do and we'll do it for you.' And I was like, 'Can we work together?' When you work in a collaboration, you have to consider the different voices because you come from different ethnographic backgrounds. It's a cultural gap, it's a communication gap, and we have different aesthetics. So there are lots of bridges to cross."

Once they were on the other side, they created eight pieces of work: three self-portraits, in which the Shaikhs and one of their employees are dressed like Manish Arora models; three embroidered motifs; one panel piece; and an eight-minute-long documentary. Called Voice of the Embroiderer, the works were shown at Clark House Initiative, in Colaba, last month, followed by a panel discussion with the three of them.

"The exhibits had a very symbolic correlation to their lives because it's such a contrast to this practice of making and creativity," says Braganza. "From the outside, you look at it as just embroidery and this stylisation of decoration on a garment. But they live in a condition that is not seen. You don't see these embroiderers, you never know where they live, how they live, the struggles they go through to make a living. They don't get paid a lot and their work is not appreciated. They are fighting for an age-old craft tradition and [losing work to] digital embroidery." Istiaq mirrors this when he says, "Many people are leaving this line of work. In our heart, even we feel we should leave. But, we also don't know any other work. Hum log zari ka kaam karke phas gaye." Braganza's art project, in its own small way, is an attempt to rafu that.

To get an artwork designed by them, contact Ashfaq Shaikh on 9619959189.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!