Faulty design and the absence of a promised service road along a national highway in Mahabubnagar, Telangana, has created a male-less village of NH44 widows

Korra Ashli. Lost her husband, brother and father; supports mother and teenage son.

ADVERTISEMENT

Kothur (Mahabubnagar, Telangana): While the country’s Prime Minister’s pet dream continues to be lightning fast development as a potent tool for change, a woman living in the village of Kothur just 50 kilometers from Hyderabad, is cursing an infrastructure project that kicked off in 2009.

Patlavath Lalitha, who lives in Peddakunta Thanda, a tribal hamlet in Mahabubnagar district of Telangana, has lost five of her family to ‘development’.

The NH44 bypass near Kothur saw 141 accidents, with 90 dead, from 2013-15

On August 30, 2009, her brothers, Korra Shankar and Korra Ravi, both in their twenties, were killed along with her husband Gopal, while they were crossing a bypass on National Highway 44, a few metres away from their home. The daily wage labourers were returning after failing to find work at a nearby town. A few weeks later, she lost her father, who couldn’t bare the sorrow of losing his sons. Her elder brother, Korra Mallesh was killed at the same spot a few months back.

Every week, Lalita must cross the same bypass to take her mother-in-law to a community health centre. “Two of sisters-in-law left the village thinking it’s cursed,"”says Lalita, who identifies her age as “early thirties”, now left to fend for her three children.

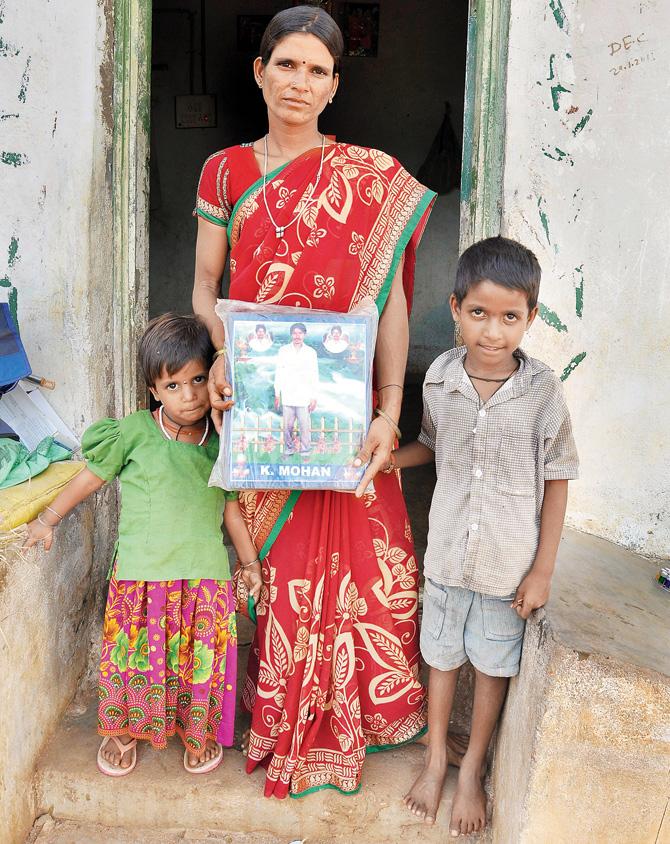

The coloured portraits she holds up of the late men in her family are a recurrent image across this hamlet associated with Nandigram panchayat, and the neighbouring Bandakunta Thanda, where most of the 90 families have lost their male members.

Korra Ashli. Lost her husband, brother and father; supports mother and teenage son. Pics/Vijay Bhaskar Rao

The bypass has claimed 80 lives in the last five years — 40 of them residents of Peddakunta, while five lived in Bandakunta,

and the remaining belonged to nearby villages.

When the idea of a bypass for NH44 was initially mooted, the residents had hoped that a service road would allow them safe and easy access to Nandigram village, the panchayat headquarters five kilometers away, the seat of a school, hospital and shops. Once the bypass was ready, the hit-and-run incidents began around 2006.

Korra Sharada. Supports a son and father-in-law

Korra Sharada. Supports a son and father-in-law

Strangely, NH44 which connects Bangalore to Hyderabad is an accident hotbed, made worse by heavy vehicular traffic. The 115 km stretch of the highway around Adilabad district is another dangerous spot, with straying of animals surprising drivers and poor maintenance of plantation on medians which masks the presence of animals crossing the stretch.

The first victim from the village died in January that year when a speeding car knocked him down. Since then, 40 men from Peddakunta have been killed leaving behind a village of widows.

The Shadnagar community health centre is where all victims are usually brought in, unless they are critical, in which case they are ferried to the Hyderabad Government Hospital. Dr Jhansi Rani, superintendent of the health center, admits that they lack orthopaedic and trauma care experts, most vital to this location.

Korra Mani. Lost husband; supports two daughters

Last month, when three people were killed at the bypass, angry villagers blocked traffic, demanding immediate safety measures. The police and panchayat members cleared the traffic promising an early solution.

Nandigram sarpanch Krishna says this is the case after every accident. “We assure the locals but we know in our hearts that these are mere assurances,” he says.

A police official from Kothur police station, requesting anonymity, says, he has witnessed close to 12 accidents occur at the spot. “It is difficult to nab drivers involved in hit-and-run cases. At times, we try to sound out staff at the next toll gate, but it hadn’t yielded much result.”

The apathy is evident at the village in the form of locked homes, with families having left Peddakunta.

Patlavath Lalita. Lost three brothers and husband; supports mother-in-law and three sons

Those who stay behind, like Korra Mani, have to struggle to earn a living and fend off men who see her as easy prey. Mani lost her husband Chander, a construction worker, in July 12, 2012, to the killer road. Her daughter, a class 10 student, faced harassment from men from nearby villages. “They think we are available; making a pass is normal,” she says, adding that she had little choice but to pack-off her daughter to a government hostel in Kothur.

Korra Sharada, 24, was told her husband, Raju, was killed on March 18 this year at the bypass when he left to find work in Shadnagar. Married to Raju as a child, she is now fending for herself, her father-in-law and her one-year-old son. “I am not educated; I don’t have parents. I must step out every day to find some work as coolie. Every time I cross the bypass, my husband’s face flashes before my eyes. He lay there in a pool of blood.”

Korra Nanu. Lost her husband; supports two children

Korra Ashli, the widow of late Korra Madhu, says it’s the panchayat’s duty to offer women like her employment. “I lost my husband, and my brother to the highway,” she says. Her teenage son must cross the bypass to get to school. “It’s a nightmare until he returns home safely.”

Devendra Goud, urban infrastructure expert, says the onus lies on the National Highway Authority of India, for building a bypass that doesn’t incorporate safety guards. Over-speeding, poor illumination and faulty road design are three key reasons for most accidents, he says.

Given the numbers, one would imagine that the state machinery wing into remedial action.

Mahabubnagar MP, AP Jitendra Reddy and Telangana Rashtra Samiti (TRS) Shadnagar MLA, Anjaiah Yadav, visited the villagers recently, who submitted a list of demands. Reddy says, in 2014, he had raised the issue in Parliament twice over and also written to the NHAI, but little came of it.

Former MLA of the Congress, Pratap Reddy says he has taken up the issue repeatedly in the united Andhra Pradesh Assembly but has failed to receive a response.

Hyderabad’s Joint Transport Commissioner, T Raghunath, admits that in the last one year, 300 deaths have been reported on NH44. One of the main reasons for accidents at the Kothur bypass, bisecting the tribal hamlets and the village panchayat, is the non- construction of an underpass. The introduction of speed breakers and signage alerting drivers and pedestrians to accidents could help too, he believes.

Meanwhile, the authorities at the Hyderabad outpost of NHAI did not respond to this paper’s queries on the issue of allegedly faulty road design.

However, one official, on the condition of anonymity, said it was impractical to illuminate hundreds of kilometers on the national highways, but added that lights could easily be installed specifically at accident-prone spots along killer highways.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!