A two-year-old artist collective in Mankhurd is bringing together architects from high-rises and activists from the slums under one roof

Children in the after-school programme started by Samooha

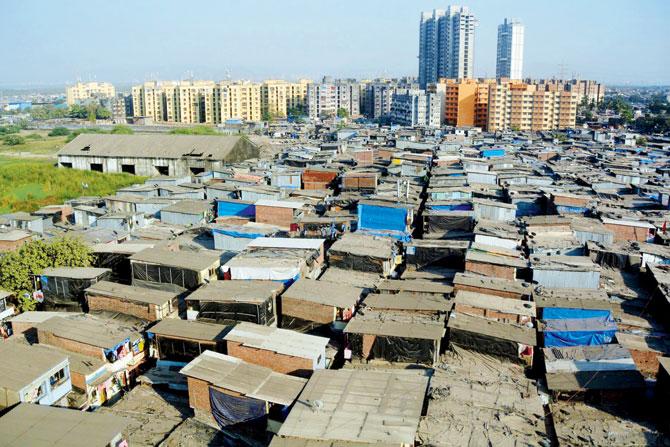

It's easy to become an activist when the roof above your head is on shaky ground. Housing activists Jameela Begam Eathakula, 36, and Santosh Thorat, 42, have grown up with the sight of bulldozers behaving like earthquakes on their homes. They are the residents of Sathenagar, in Mankhurd, M Ward, which, according to Thorat, has the lowest standard of living in the world. "The human flesh that is left over after surgeries is burnt here [at an incinerator run by SMS Envoclean]," he says.

ADVERTISEMENT

"The smoke from that chimney is killing us. Mumbai's entire garbage is dumped here [in nearby Deonar]. The TB here is third-stage. From every corner, there is pollution."

In 2004, 80,000 houses across the city had been razed, as part of a demolition drive approved by late CM Vilasrao Deshmukh, which rendered nearly three lakh people homeless. Thorat's "very well-made" home was demolished, too. "It was made of wood, two floors, four-foot-high walls, tiles," he says, in Mumbaiyya Hindi. Eathakula, in chaste Hindi, adds, "Activists such as Kaushalya Salve, Mohan Chauhan and Raju Bhise used to come here and tell us, 'Your rights have been abused.

Santosh Thorat, Dr Vyjayanthi Rao, Manisha Agarwal and Jameela Begam Eathakula at Sathenagar. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

You will have to stand up for your house.' After that people started protesting together, and Medhatai [Patkar] came onboard." They became involved with Patkar's Ghar Bachao, Ghar Banao movement, and to this day, continue to attend rallies related to the cause. But, by 2015, their fight had taken a different turn. "I started thinking that struggle alone isn't worth it," says Thorat.

At the same time, they became close to cultural anthropologist Dr Vyjayanthi Rao, who teaches at City University of New York, and through her, architects Manisha Agarwal and Shantanu Poredi from Mumbai, and Anand Patel and Aparajita Basu from Ahmedabad. They came together to form Samooha. "We began to protest through art," says Thorat.

First public outing

Samooha's first artistic engagement was at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB) in 2016, at the invitation of then-curator Sudarshan Shetty. Called On Stage: Sathenagar Here, it was an interactive installation that showed a mini version of Sathenagar. "It was an interpretation of a framework with bamboo, as that is one of the basic materials used to build a new settlement," says Agarwal. "We wanted to create a framework for the people of Sathenagar: capturing their stories, performances, and cultural aspects of living as a community. There were films made by Santosh and Aparajita.

There were photographers - Shankar Mote from here and Rajesh Vora - who took two sets of photos: how an insider looks at it and how an outsider looks at Sathenagar. And there were some very interesting spatial learnings. The structure and frame of each house in essence is similar, but each space within is completely different. The materials, the doors, the stairs to reach up: every element and the way it's crafted is with a certain rationale or flexibility. It was interesting to see [and recreate] everything that was accommodated within that frame. And then there were performances."

Sathenagar is named after Annabhau Sathe, a Dalit folk poet and writer whose image is omnipresent in the area. One exhibition accompanying the installation carried the cover art of his novels. "What we found here was that there's an interest beyond popular culture and Bollywood," says Rao. "People were reconnecting with forms like tamaasha and lavani. We took two lavani performers, and reconnected to Annabhau Sathe, who has written some lavanis as well."

A free-flowing collective

Samooha doesn't have a fixed mission or fixed personnel. "It's very flexible and really open to anybody's collaboration and input," says Rao. "We haven't even thought as far ahead as calling ourselves an institution." When asked, they say in one voice that they weren't thinking of a collective; they just found common ground.

"The whole idea is to learn from each other," says Rao. "Caste is divisive in India in general. But, the conversations that we were having were about not losing the identity that caste has given to each of us, but thinking of it as a possible unifier. There's a very rich intellectual and cultural life that is thriving here. We need to think beyond our own communities. Why should upper-middle-class folks like us be concerned about making something together? Our society will continue to remain divided unless we do things together, unless we figure out a way of collaborating and actually making something together."

Since KMB, Samooha has achieved two feats: it has created an after-school programme called Annabhau Sathe Manav Vikas Seva Sangh - called Amavas in short - with help from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and a media centre that includes a television set, computer and projector. Around 120 kids from Class I-X attend the programme. "They [kids] need to learn how to live life. We don't want a beggar's child to become a beggar," says Thorat.

The programme was created by "a desire to provide a certain framework for pedagogy and education, which goes beyond our school system," says Rao. "Any way that fosters creativity should be part of the DNA of Samooha." For instance, the media centre's role is to encourage talent in Sathenagar. "The children of rickshaw drivers and carpenters can dance or sing or act," says Thorat. "[Through digital mediums], we want our stories to go out and their talent to get a platform."

For those living in Sathenagar, the path Eathakula has taken can be the one to follow. "When I was involved in andolans, I was only Std X pass," she says. "But now, I have done BSW [Bachelor's in social work] from IGNOU, and I'm pursuing MSW. We take classes every fortnight in Sathenagar to explain to the people their constitutional rights, child rights and gender rights. But [Samooha is important because] to create employment and employed in slums like these is very difficult. Activism can't create employment."

A brief history

Sathenagar was established in 1982, after Babasaheb Gokhale rounded up members of the Matang community into one area in Mankhurd. Today it has about 15,000 homes. Samooha's next move is to collaborate with members from Van Alen Institute in New York, which comprises architects and designers, who visited the neighbourhood in November 2018.

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and also a complete guide on Mumbai from food to things to do and events across the city here. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!