Product design historian, Abigail McGowan comes to Mumbai to discuss how print ads of the 1930s helped create the modern apartment

Abigail McGowan

ADVERTISEMENT

Less than two minutes into our conversation with Abigail McGowan at Vikhroli's Godrej Archives, it's easy to gauge why India, and the city in particular, fascinate her.

She is dressed like any smart Mumbai resident would in muggy June, in airy casual Indian wear. "I left pleasant Vermont for sultry Mumbai," she laughs, a bead of sweat glistening on her temple.

Abigail McGowan. Pic/Sameer Sayyed Abedi

But the weather is hardly a bother for the Associate Professor at the Department of History, University of Vermont. Bombay is a fascination, and currently, a preoccupation, as McGowan prepares for a talk inspired by how the city consumed durables and sharpened its style, scheduled for Tuesday at Godrej Hubble.

Domestic Modern: Redecorating Homes in Bombay in the 1930s is going to examine city-based designers, producers and elite consumers' role in bringing modernism into Indian homes through new architectural ideas and fresh consumption practices.

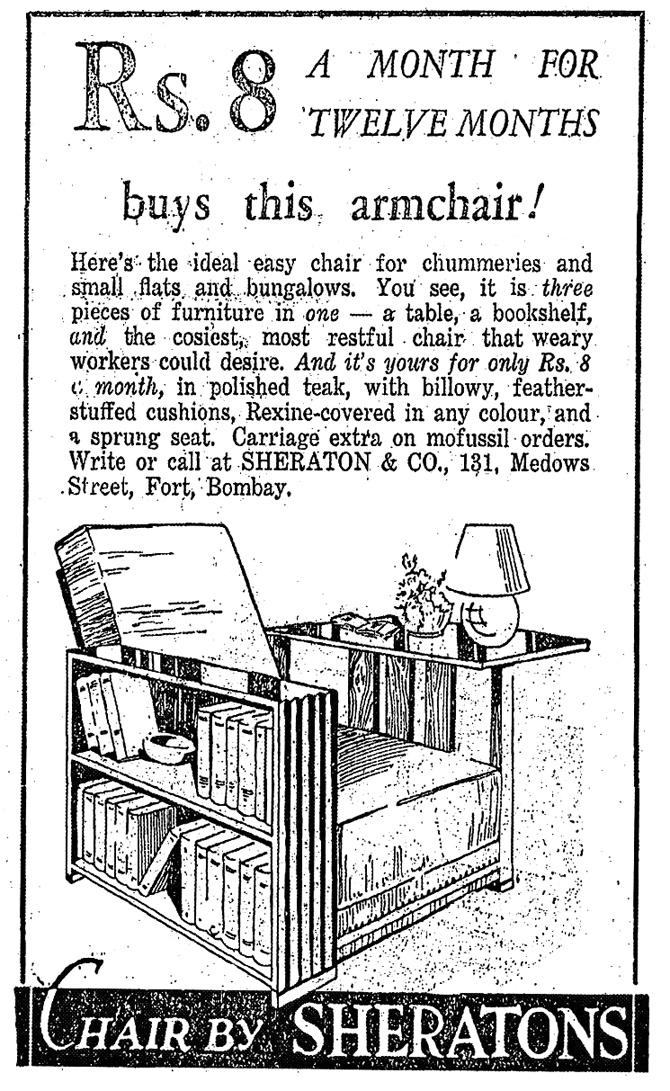

It's affordable Though a lot of the products were expensive, you see a constant reassurance in the ads about them being not-as-expensive-as-you-think. Pic Courtesy: Times of India, 12 March 1934, p. 9

The decade of choice is interesting, we tell her. "It's the first time that furnishings moved into the public eye through ads and public exhibitions; there is little record of the practice before this. Ads for furnishing fabrics, blankets and curtains appear in the Times of India Annual. It's not until the 1930s that newspapers began advertising furniture companies in a big way.

Events like the Ideal Home Exhibition of 1937 emerged to celebrate and offer a record of the dense furnishings imagined for Bombay's modern homes," she says.

Consumer is king: “I see an increasing trend towards personalisation in the text as compared to what you see in the 1920s or 1910s, when ads weren’t as free with visuals, and more static in composition,” says McGowan. This ad speaks of a 3-uses-in-1 chair that can be yours for an EMI of just Rs 8 a month. Pic Courtesy: Times of India, 9 July 1934, p. 12

While up until then, women —advertising's chief target — were tutored on household practices, this decade saw a shift to inspiring them with reference to style.

It was also a time when the city's privileged saw themselves as cosmopolitan in a confident way. They found it necessary to integrate new ideas, habits and a contemporary outlook into their domestic space.

For the European and Indian: There is an attempt to reach out to Bombay’s Europeans. But there is also a strong interest in Indians as consumers. Some ads depict women in saris, usually the kind worn by Parsi women. Pic Courtesy: Times of India 17 September 1934, p. 5

McGowan's research revealed that European firms that dealt in exhibits and furnishings weren't the only players. Prominent Indian architects, furniture makers, tile companies and decorators also played a key role. The new emerging consumer was "elite, and the furniture was expensive," she says. It demanded space at a time when rents were high, and flats cramped. Incomes were struggling to rise again after the Great Depression. "Advertisements, therefore, made attempts to suggest that the products they hawked were not superfluous luxuries."

By the 1930s, this was a city that spelt progress, and the modern home was symbolic of this shift, says McGowan, poring over catalogues shared by Godrej Archives' chief archivist, Vrunda Pathare, some of which have been turned to slides that will be used at this week's talk.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!