Last week, Mumbai became the first city in South Asia to draft a climate change mitigation action plan. mid-day got top names in urban planning and conservation to examine the fine print and give you their verdict

Pic/Bipin Kokate

Image caption: The Coastal Road Project has led to reclaiming large swathes of land from the sea like at Haji Ali. Urban planners say it’s not just about the beach, but what you do with the sea by constructing inside it that decides tide and climate change

ADVERTISEMENT

One step closer to safeguarding our future, and that of the planet,” Aaditya Thackeray, state minister for tourism and environment tweeted on March 13, after releasing the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP) 2022, a one-of-its-kind document on the financial capital’s future environmentally-conscious policies. With this, Mumbai not only became the first city in the country to come up with an action plan, but also the first South Asian city to take the lead in mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change. Developed by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) with technical support from the World Resources Institute (WRI) India and the C40 Cities network, MCAP intends to offer a “robust roadmap in the run-up to 2050”—the year by which the city hopes to achieve net-zero emission.

As ambitious as the goal is, the climate change projections for Mumbai mean that such a policy was imperative and urgent. As per a 2019 study by scientists Scott A Kulp and Benjamin H Strauss of Climate Central, an independent organisation of scientists, journalists and researchers, Mumbai city stands the risk of being submerged by 2050. Another study from over 10 years ago, led by Nicola Ranger, had highlighted that the likelihood of urban floods, such as the 2005 deluge, would more than double by 2080. The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change A6 Atlas (IPCC 2021) projections for the Mumbai region, stated that “by the end of the century, the mean temperatures [in the city] are expected to increase by 1.5-2 degree Celsius under RCP [Representative Concentration Pathways] 2.6 and by 4.5-5 degree Celsius under RCP 8.5. The maximum temperatures, specifically the total days above 35 degree Celsius per annum, are expected to increase by 20-30 days under RCP 2.6 and by more than 40 days under RCP 8.5.” RCP is a greenhouse gas concentration trajectory adopted by the IPCC.

The MCAP hasn’t shied away from listing out these projections; neither does it hold back from pointing out the dangerous position Mumbai finds itself in. As Thackeray says in the report: “A day’s delay in taking decisive, inclusive climate action is akin to adding months of uncertainty and vulnerability to the lives of our future generations. The climate crisis is no longer an event in the distant future but a reality unfolding in our everyday lives.”

Environmentalists, urban planners and architects alike have lauded the BMC’s decision to think on its feet, but feel that most of the ideas suggested would require deeper investigation and thought. “This is a super positive move. The fact that the government is speaking about it, is an important start. What would have been worse is not acknowledging that there is a problem,” Alan Abraham, joint principal architect of Mumbai-based Abraham John Architects and co-founder of Bombay Greenway tells mid-day. Abraham, who has been working on urban design solutions, however, adds that the road ahead is crucial. “They now have to act on what they are saying. They’ll need to know the deliverables and set targets for it. These deliverables should also be tangible—we [the residents] should be able to see and feel it.”

Dr Anjal Prakash, Stalin Dayanand and Pranav Naik

Dr Anjal Prakash, Stalin Dayanand and Pranav Naik

Mumbai city, according to MCAP, faces two major climate challenges—rising temperatures and increasing number of extreme rainfall events (ERE). Many of the action points suggested in the 240-page document, available on their website, are intended to address these issues. Key priority here is developing its environmental infrastructure, which includes increasing vegetation cover and applying scientific knowledge in tree planting to reduce heat and flood risk; protecting, restoring and enhancing Mumbai’s diverse natural habitats, and increasing per capita open space from 1.8 square metres to 6 square metres. “This will increase flood and heat resilience, make space available for physical activity and improve public health as co-benefits,” the report points out. The BMC will also reduce landfilled waste by source reduction and reuse, and scientifically manage landfills to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) and pollution.

Dr Rakesh Kumar, former director of National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) and Officer on Special Duty at Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, says that it’s encouraging that not just bureaucrats, but politicians too, are showing keenness to address and talk about climate change and its impact on the city. “The main concern, however, for everyone would be about where the finances will come from [for these initiatives]. The assumption is that the BMC has a lot of money, and that they’ll be able to take care of this. But, climate finance is a completely different ballgame.” It’s going to cost more than any of the mega projects that the city is currently undertaking, he says.

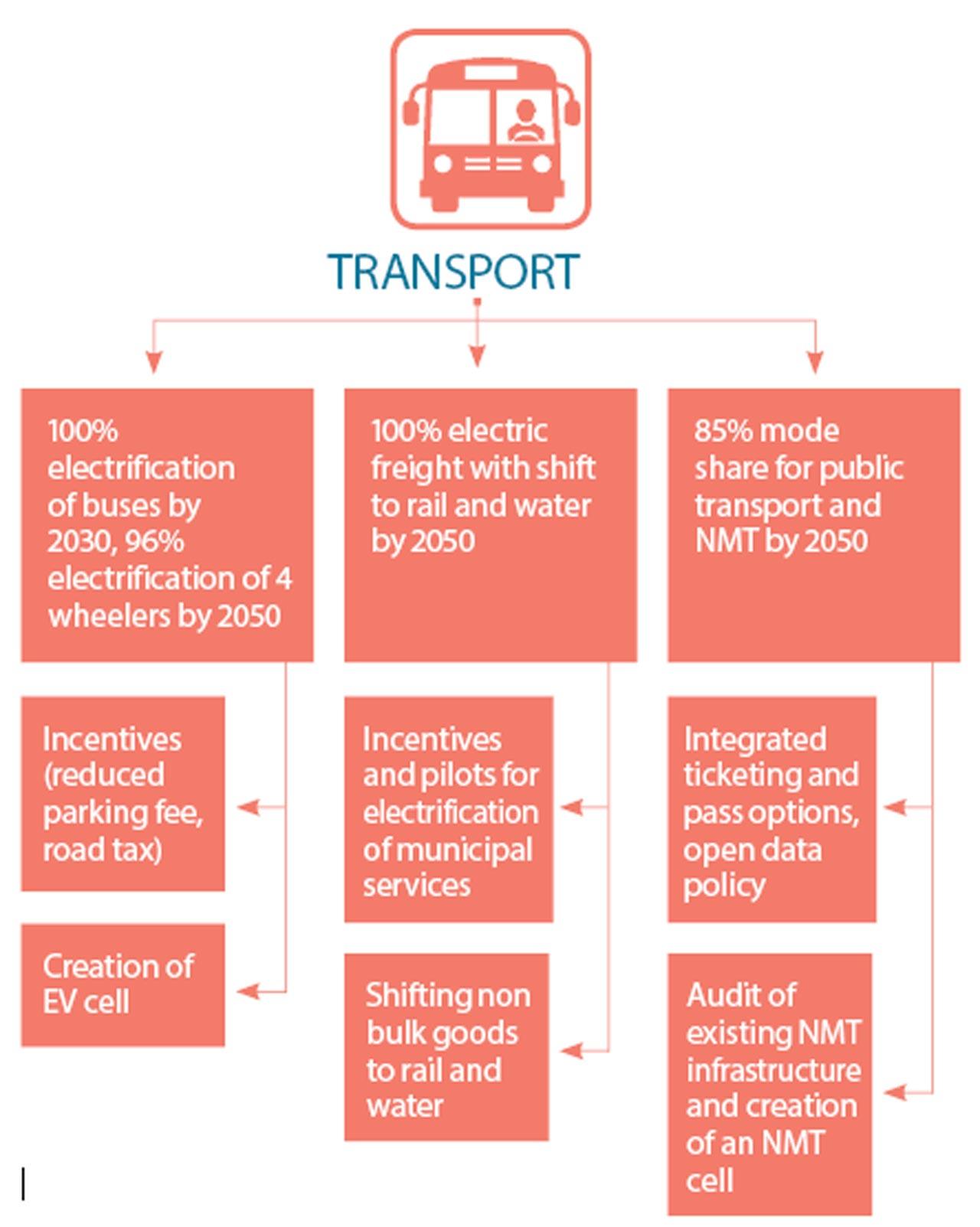

Strategies planned in the transport sector. Courtesy/Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022

Dr Kumar cites the example of Mumbai’s housing issue, which he says is most critical right now. While MCAP has proposed developing climate-resilient buildings, the need of the hour is to protect the existing built infrastructure. “Even a 10 cm sea-level rise can have a multiplied effect on the storm surges. When you have high winds and rain, the height of the waves could increase by several metres. This could pose a serious threat to those living near the coast. We will need high infrastructural investment to protect these buildings and roads from storm surges.” The bigger problem is the city’s dense residential pockets. Mosquito breeding has been on the rise, Dr Kumar says. The MCAP report states that “high heat and humidity days, would [also] increase heat exhaustion and result in a sudden spike in heat-related deaths and illnesses”. “The city’s disease burden is going to be extremely high. For that we would need more doctors, nurses, and good, affordable hospitals,” Dr Kumar says, adding that any action plan needs to consider setting aside finances for the same.

Another focus of the new action plan is “improving reliability, interconnectivity, accessibility, safety and information delivery of public transport services” and “access to non-motorised transport (NMT) and infrastructure”. The MCAP has already put down a roster of priority actions for the next three years. Some of these include conducting an audit of the existing pedestrian infrastructure (coverage, encroachments, lighting, etc.) by next year; creating a multi-stakeholder NMT cell within the transport department by 2024, and implementing pilot pedestrianisation projects in high footfall areas, such as Central Kala Ghoda, with ramps on curbs, street furniture and lighting by 2025. “Anything the BMC does on pedestrianisation is welcome. Having said that, the approach has to start with the big picture—the land/sea edge, city rivers, changing geography, the national park, every open space, the networks of roads down to individual plots. Any approach that does not recognise these hierarchies is superficial,” feels architect and academic Mustansir Dalvi, adding “Roads in the city too have hierarchies based on very fast moving traffic [Coastal Road, Bandra Worli Sea Link, Eastern Freeway, etc.] to the main arterial roads connecting the city to the more local roads to the ‘last mile roads’ leading to homes and offices. Pedestrianisation should be based on this. Unfortunately, in the past we have looked at all roads in the same way, or not looked at them, so encroachments fill the vacuum.” Dalvi feels that in the current plan, the stress is on objects, street furniture, and the likes, “rather than on the flows of the city and its citizens”. “Also, look at the time frame. Are these to study, or implement? We live in a very fast changing world.” His gripe is that “the large agencies that they [the BMC] have mandated to carry out the projects, ignore the large community of architects and urban designers already present in the city, who have “ background, competence and insight to approach pedestrianisation in the city holistically”. “The BMC should place trust in them, and listen to their advice,” says Dalvi.

Environmentalist and founder of Awaaz Foundation Sumaira Abdulali, who lives in Pali Hill, says the neighbourhood is marred by continuous deafening construction work. The BMC, she alleges, has forgotten to address noise pollution in the plan. A recent report published in Science Daily stated that “road traffic in European cities exposed 60 million people to noise levels harmful to health”. Pic/Atul Kamble

Environmentalist and founder of Awaaz Foundation Sumaira Abdulali, who lives in Pali Hill, says the neighbourhood is marred by continuous deafening construction work. The BMC, she alleges, has forgotten to address noise pollution in the plan. A recent report published in Science Daily stated that “road traffic in European cities exposed 60 million people to noise levels harmful to health”. Pic/Atul Kamble

It’s been over a month since Mumbai-based environmentalist and founder of Awaaz Foundation, Sumaira Abdulali, demanded that a public health advisory be issued on days when the city experiences hazardous air quality. She hasn’t heard back from them, she tells mid-day.

Abdulali says that the MCAP has also turned a blind eye to noise pollution. A recent report published in Science Daily stated that “road traffic in European cities exposed 60 million people to noise levels harmful to health”. The researchers also established associations between noise and mortality caused by ischaemic heart disease. “It can be even more damaging than air pollution. By leaving it out, you aren’t reassuring people,” she thinks.

The Coastal Road project underway at Marine Drive. According to Dr Rakesh Kumar, Officer on Special Duty at Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, “Even a 10 cm sea-level rise can have a multiplied effect on the storm surges. So, when you have high winds and rain, the height of the waves could increase by several metres. This could pose a serious threat to those living near the coast. We will need high infrastructural investment to protect these buildings and roads from storm surges.” Pic/Bipin Kokate

The Coastal Road project underway at Marine Drive. According to Dr Rakesh Kumar, Officer on Special Duty at Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, “Even a 10 cm sea-level rise can have a multiplied effect on the storm surges. So, when you have high winds and rain, the height of the waves could increase by several metres. This could pose a serious threat to those living near the coast. We will need high infrastructural investment to protect these buildings and roads from storm surges.” Pic/Bipin Kokate

As per the MCAP, nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is one of the major pollutants in Mumbai, and “most of the monitoring stations have recorded a high concentration of this for the years 2010-2020, beyond the annual permissible limit of 40 µg/m3”. The pollutant, according to the report, is majorly concentrated in the central and south-eastern parts of the city. mid-day on March 24 had reported that the BMC is working on forming teams at the ward level to carry out data surveys on air pollution risks, as proposed by the MCAP. “If you are going to be leading the way [when it comes to dealing with climate change], I don’t think you can start by allowing things to proceed the way we are. We are already late in generating [this] data, and while this is a good thing and is crucial for future actions, the data that’s already in existence is not being used or made available to citizens,” she says.

Conservationist Stalin Dayanand, who works with the environmental NGO Vanashakti, says while the MCAP has mentioned that “wind augmentation and purifying units (WAPU) have been installed at five traffic junctions in Mumbai to purify the ambient air quality”, this doesn’t really help address the root problem of pollution. “Installing air purifiers is like putting band aid on a cut artery.”

Dr Rakesh Kumar

Dr Rakesh Kumar

Many experts are even more surprised that the MCAP remained tightlipped on the BMC’s R12,750 crore-dream project—the Coastal Road— even though the IPCC in its recently released assessment report has termed it “maladaptive”. Earlier this month, a group of Mumbai architecture practices, urban planners, designers, and principals or colleges of architecture, had sent a joint letter to CM Uddhav Thackeray, the environment minister and BMC commissioner Iqbal Singh Chahal, proposing a “slight realignment” of the Coastal Road.

They suggested moving “as many open spaces to the seaside as possible”. This, they said, would enable a world class waterfront open to all citizens “retaining the much necessary vista on to the open uncluttered horizon; the addition of continuous bicycle paths along the length of the reclamation, would allow one to cycle along the entire length of the city, thereby reducing the load on the road; as well as public transport on the north-south corridors on the west side”. The open public space would also be better protected from future proposals for built-up development on the sea-side edge, they wrote.

![Land surface temperature increase over 10 years (range from 2005-2010 [top] and 2015-2020 [bottom]) along Andheri-Ghatkopar link road due to heat island effect. Courtesy/Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022](https://images.mid-day.com/images/images/2022/mar/buid-big-g_e.jpg) Land surface temperature increase over 10 years (range from 2005-2010 [top] and 2015-2020 [bottom]) along Andheri-Ghatkopar link road due to heat island effect. Courtesy/Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022

Land surface temperature increase over 10 years (range from 2005-2010 [top] and 2015-2020 [bottom]) along Andheri-Ghatkopar link road due to heat island effect. Courtesy/Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022

Architect and urban designer, Pranav Naik of Studio Pomegranate, is one of the signatories. “On the one hand, we are reclaiming our coast [for the Coastal Road project], and on the other, we are talking about restoring our coastal ecology and fish-hatching areas. It all looks great on paper, but it feels slightly insincere. They haven’t even spoken about the effect of the coastal road on the city.” Naik gives the example of the Bandra Worli Sea Link, which led to erosion of beaches at Mahim and Dadar. Incidentally, MCAP states that the overall coastline in Southern Mumbai has not “changed much owing to the tetrapods stone blocks which line the sea”. “The physicality of the beach is not just the beach itself, it’s also how the tide comes in. When you change that by putting a big pole in the middle of it, it’s going to change permanently. They need to mention how they are going to mitigate its effects.” Dayanand says that there is “zero attempt on part of the government to retrace their steps and stick to the original design of making the Coastal Road on pillars” instead of reclaiming the sea, when they are fully aware of the damaging effects of rising sea levels, a proven outcome of reclamation.

Abraham thinks that the focus should have been on creating better roads on land than construct one in the middle of the ocean. “If you have better roads on land, you’ll have fewer traffic jams, a smoother ride, better transport, and end up with lower pollution and less of a heat island effect.” He feels that the current actions by the agencies are diametrically opposite to what is being spelled out in the MCAP.

Speaking with mid-day, Dr Anjal Prakash, research director, Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business, and IPCC lead author of chapters on Cities, Settlements and Key Infrastructure, says that the Coastal Road and a few other projects will require a re-evaluation. “But, the over-arching goals set by the MCAP tick all the boxes. The actual problem begins when it comes to implementation, and that’s something that we need to watch out for. A good starting point would be to carry out ward-level planning. They can also have a watch committee of scientists, planners, academics and journalists, that meets regularly. It’s important for a progressive city like Mumbai to be open to checks and balances.”

2024

Year by which BMC plans to create an NMT cell within the transport department

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!