This idea takes ritual shape in many Hindu ceremonies, where knotting draws attention to social responsibilities, desires and demands, while unknotting is an indicator of renunciation

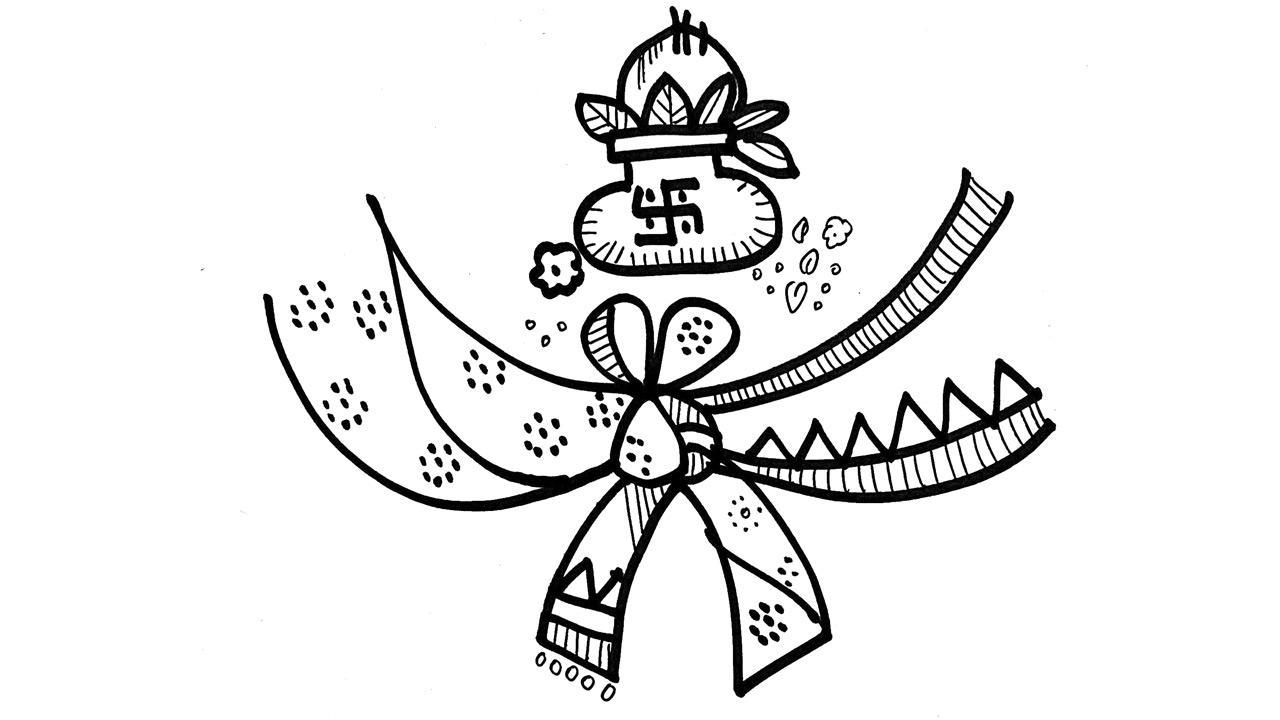

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

In Hindu metaphysics, yoga is the practice of untying mental knots. Bhoga is the experience of life that creates these mental knots. When we consume life, we experience hunger, fear, delight, jealousy, attachment, rage, greed, frustration, hatred, joy, and these various emotions and stimulations cause our mind to be knotted. These mental knots can be removed through introspection and intellectual analysis (gyan yoga), devotion and emotional surrender (bhakti yoga) and ritual activity and social responsibility (karma yoga).

ADVERTISEMENT

This idea takes ritual shape in many Hindu ceremonies, where knotting draws attention to social responsibilities, desires and demands, while unknotting is an indicator of renunciation. In tantra, the untied hair is a mark of freedom. The tied knotted hair is a mark of domestication. In Vedic rituals, the sacred grass is tied with a knot around the finger, and the sacred thread is tied with a knot over the left shoulder, to transform the body into an ‘auspicious’ body, abode of divinity.

During Hindu pujas, the priest often ties a knot on the wrist of the yajaman, or ritual initiator. This is the sankalpa knot by which the yajaman expresses what desire he or she wants fulfilled through the ritual. We perform rituals because we desire something from the deity. And so, our intention is given shape through the sankalpa knot on the wrist. It reminds us of what we want in life, why we seek the gods.

This practice spread to Indo-Islamic communities which is why tying coloured threads on the windows of dargahs is a common practice in India. People visit the tombs of holy men to get something they desire. This is expressed through a ritually sanctioned performance: tying the knot on a lattice window.

Weddings are a time when the knot is tied—literally. The end of the bride’s garment is tied to the end of the groom’s garment. The couple then moves around the sacred fire, publicly demonstrating their union. In South Indian communities, the necklace or ‘thali’ is tied by the groom around the bride’s neck.

It is interesting to note that in many temple rituals, knots are forbidden. The priest performing the ceremony, the yajaman too, wears a lungi or dhoti but uses “tucks” rather than “knots” to keep the fabric wrapped around the waist. Even garlands avoid using threads that need to be knotted, but instead using vines of plants that are simply twisted around. In Vaishnava temples of South India, the garland (identified mostly with the poet-saint Andal’s garland) is not tied at the ends, and so hangs from the shoulder of the deity. Knot means samsara, the wheel of rebirths. It means entrapment. It means bandhan, or fetter. The open garland is perhaps about challenging the limitations it imposes.

Yet, the trap is also about responsibilities of the household. Sisters tie the thread around brother’s wrists during ‘Raksha Bandhan’—a reminder of a brother’s duty to care for the welfare of the sister even after marriage. It is a ritual of siblings unique to India, popularised in the Indo-Islamic period, with folktales of the thread being tied by Hindu women on Muslim warriors or Muslim women on Hindu warriors. This is a knot of responsibility, and a circle of protection, that became a mark of honour.

Devdutt Pattanaik writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at devdutt.pattanaik@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!