He spilled his semen on the ground. The semen lay on the grass and a female deer ate it

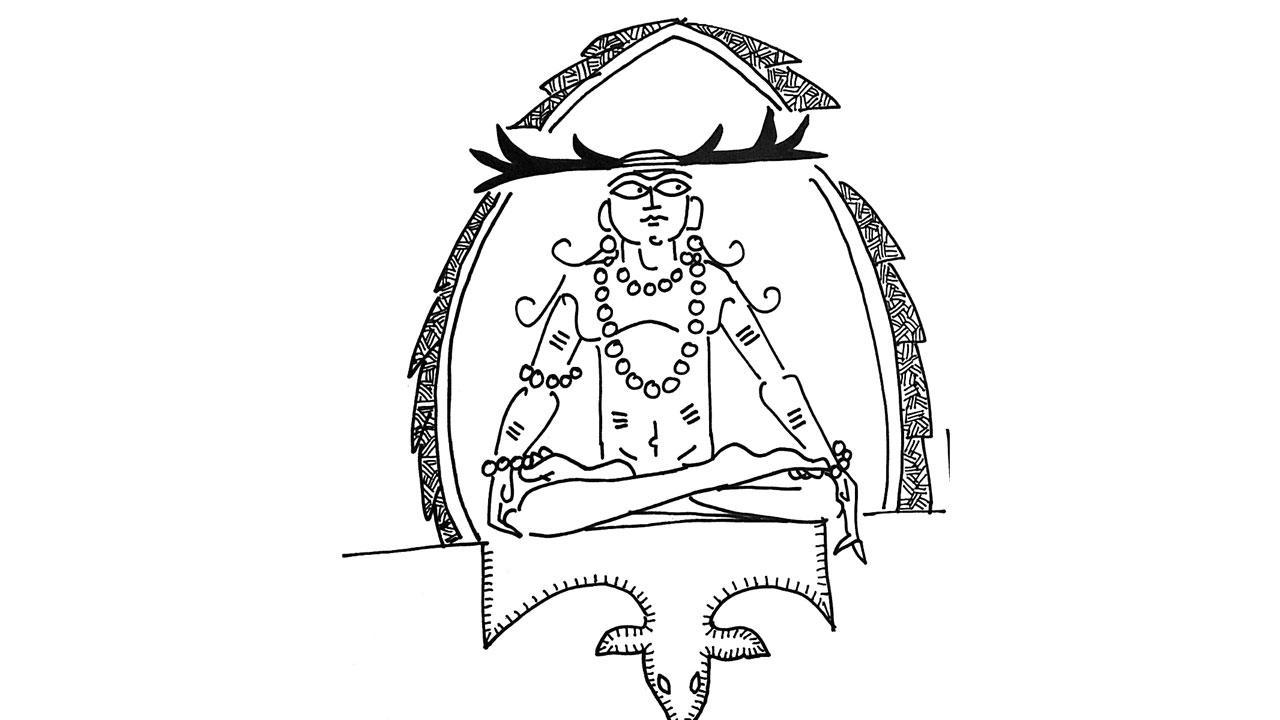

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

The story of Rishyasringa Muni is found in the Ramayana. Dasharatha had three wives, but no children. So, he called a sage to perform the ritual that would get him children. The rishi selected was Rishyasringa Muni.

The story of Rishyasringa Muni is found in the Ramayana. Dasharatha had three wives, but no children. So, he called a sage to perform the ritual that would get him children. The rishi selected was Rishyasringa Muni.

ADVERTISEMENT

In Odia miniature paintings, Rishyasringa is depicted as having two horns. His father Vibhandaka was a rishi. Vibhandaka was once performing tapasya, and could not control his passions at the sight of an apsara. He spilled his semen on the ground. The semen lay on the grass and a female deer ate it. The doe then gave birth to Rishyasringa Muni, which is why he was born with two horns.

The child was raised without any access to women. The resulting celibacy gave him so much power that he could even stop the rain from falling. This resulted in drought and childlessness in the land. To remove the spell of drought and childlessness, a king had to send a woman to seduce Rishyasringa Muni. Since Rishyasringa Muni had never seen a woman before, he wonders what kind of man he is encountering. The woman then educates him on female anatomy and in the art of erotica. Rishyasringa Muni surrenders to his desires. When the two make love, the hermit loses his magical powers and the spell of drought and childlessness is broken.

In some stories, the woman was the king’s daughter and, in other stories, she is a courtesan. The king is Rompada. In some stories, Dashratha is the father who gives his daughter, named Shanta, to Rompada, who turns the horned hermit into a horned householder. Besides Ramayana, this story is also found in Buddhist literature, where the sage is called the Ishishinga. Here the story is restricted to the seduction of the sage. It evokes the tension between sexuality and celibacy, the householder way and the monastic order. It reveals the social cost of monastic power.

Buddhist stories of Rishyasringa Muni were translated into Chinese. They reach Japan where the story of Rishyasringa Muni becomes part of Kabuki theatre. In India, the story of the horned sage seduced by a courtesan is carved on the walls of many Buddhist stupas. In Mathura art, which is over 2,000 years old, is the image of the sage shortly after his seduction, his face looking satisfied and bewildered by the new experience.

As per a Chinese monk, Xuanzang, Rishyasringa Muni lived in the Gandhara region, in the Swat valley. Today, many people in North India, believe that Rishyasringa Muni lived in the Banjar valley of Kulu, in Himachal Pradesh and his wife, Shanta, was the eldest sister of Ram. The hot-water pond, Rishikund of Bihar, is linked to Rishi Vibhandak, father of Rishyashringa. In South India, Sringeri Matha is associated with Rishyasringa Muni. Thus, you find the story of Rishyasringa Muni spread across Buddhism and Hinduism. In geography, it encompasses the Kulu and Swat Valleys in the north, Bihar in the east, and the Sringeri in the south. An ancient and widespread story indeed.

Devdutt Pattanaik writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at devdutt.pattanaik@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!