The annoying tradition of brands appropriating the rainbow flag during the Pride month of June to sell their wares has us digging for historical clues on colour as code, and how India’s young designers are choosing to express its vibrant legacy

Shoe designer Jeetinder Sandhu introduced limited edition Rainbow brogues to coincide with Pride month. “When we wear symbols of positivity [rainbow], it can become part of us assuming agency and sparks of joy,” he says

As someone who lives a queer non-binary (he/she) existence throughout the year, Delhi-based fashion consultant Daniel Franklin, 32, finds it annoying that brands resorting to marketing campaigns that ride on the Pride month flavour are routine. “My existence is not a trend for others to emulate; it is me unlearning the gendered conditioning of my childhood. It is about breaking free and having fun with fashion.”

As someone who lives a queer non-binary (he/she) existence throughout the year, Delhi-based fashion consultant Daniel Franklin, 32, finds it annoying that brands resorting to marketing campaigns that ride on the Pride month flavour are routine. “My existence is not a trend for others to emulate; it is me unlearning the gendered conditioning of my childhood. It is about breaking free and having fun with fashion.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Another Pride season is upon us, with companies chasing “rainbows” to show faux solidarity with the LGBTQiA+ movement. Gay beer, anyone? The merch

often screams tacky; some kind of straight derivative of the rainbow hues or carefully calibrated couching of #LoveisLove, and much of it rarely links with other social transformations. This mainstreaming of the rainbow aesthetic as woke material acceptance is known among the queer as rainbow capitalism or rainbow-washing.

Jeetinder Sandhu

Jeetinder Sandhu

But in a world of white noise, and sex and gender politics, a world where the first line of communication is visual, colours are integral to the human experience. Almost every protest movement has its visual signifiers: colours etched in the collective memory that create a halo effect around the cause for which they were fought. The Suffragettes’ colour scheme of purple for loyalty and dignity, white for purity and green for hope devised in 1908 by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, co-editor of Votes for Women, was an early triumph for branding. The Gulabi Gang movement of 2006 by UP’s Sampat Pal Devi to fight for women’s rights got its name from the members wearing bright pink sarees and wielding bamboo sticks.

During the Holocaust, gay men were forced to pin on pink triangle upside down, the symbol was reclaimed by the community in 1970s to protest its disturbing origins. Since 1978, when a San Francisco artist Gilbert Baker along with 30 volunteers first created the Rainbow Flag, it has become a universal symbol for the queer. The rainbow flag also had some links with Judy Garland, a darling figure among the community who sang, Somewhere Over the Rainbow in The Wizard of Oz. The Advocate has called Garland “an Elvis of homosexuals”.

Designer Mayyur Girotra (in spectacles) kicked off Pride Month in New York on June 2 with a showcase of the Aikya capsule collection. Seen here with gender-nonconforming author, poet and public speaker Alok Vaid-Menon who attended the show wearing a Girotra designed trench-coat with Kutchi embroidery and mirrorwork. Pic Courtesy/Rishika Nath (Right) A look from the collection. Pic Courtesy/Saunak Shah

Designer Mayyur Girotra (in spectacles) kicked off Pride Month in New York on June 2 with a showcase of the Aikya capsule collection. Seen here with gender-nonconforming author, poet and public speaker Alok Vaid-Menon who attended the show wearing a Girotra designed trench-coat with Kutchi embroidery and mirrorwork. Pic Courtesy/Rishika Nath (Right) A look from the collection. Pic Courtesy/Saunak Shah

Gender-agnostic or all-inclusive clothing is the central theme of Anvita Sharma’s label, Two Point Two. “The dissociation of colour and shapes is what our brand stands for.” She observes that her queer clients are experimental, and therefore, more flamboyant than their cisgender counterparts. “The grandeur of the rainbow flag as a symbol of Pride plays a major part in this extravagance,” she adds.

For Bhaane’s inaugural collection in 2019, its creative director Nimish Shah introduced T-shirts and jumpers depicting the six-colour Pride flag. “I did not do a top-up as I was in two minds about commercialising a sentiment. I live it [queerness]. I talk about it. But I avoid sartorial souvenir affront through merch.”

Fashion consultant Daniel Franklin says, “My existence is not a trend for others to emulate; it is me unlearning the gendered conditioning of my childhood. It is about breaking free and having fun with fashion”

Fashion consultant Daniel Franklin says, “My existence is not a trend for others to emulate; it is me unlearning the gendered conditioning of my childhood. It is about breaking free and having fun with fashion”

Unfortunately, the rainbow is a well marketed aesthetic and easily symbolises queer thought, Shah reasons. “This makes a subtle move rather difficult given the penchant for the queer folk’s ability to articulate and self-express. Minimising or eradicating it [rainbow] altogether would mean we have won the fight.”

On June 2 to coincide with Pride month in New York, Mayyur Girotra showcased Aikya, a line of 40 ready-to-wear garments in collaboration with Pride Google and the Indus Google Network. From concept to execution, 90 per cent of the talent that worked on the show was queer.

The only time Bhaane introduced rainbow-hued clothing was in 2019 as part of its inaugural Rising Sun collection. “I did not do a top-up as I was in two minds about commercialising a sentiment. As a brand, Bhaane is inclusive; we don’t need a souvenir to celebrate Pride month,” says its creative director Nimish Shah

The only time Bhaane introduced rainbow-hued clothing was in 2019 as part of its inaugural Rising Sun collection. “I did not do a top-up as I was in two minds about commercialising a sentiment. As a brand, Bhaane is inclusive; we don’t need a souvenir to celebrate Pride month,” says its creative director Nimish Shah

This was a show of pride as much as it was a fashion show. The designer adds that 95 per cent of the collection was created in gender-neutral styles. “My sister and I often share clothes, so I am quite comfortable designing outside the binary.”

Yet, Girotra, 42, clarifies that there is no such thing as a Pride collection. “We still went ahead because it packages hope and optimism, and educates people on love, preferences and acceptance.” The Aikya looks were a flamboyant cocktail of assured sexuality, and used textures of aari, mirrorwork and Kutchi embroideries and pops of bright colours. The label tags on the garments are sewn with quotes from queer authors or icons like George Sand and Diana Dors.

Nimish Shah

Nimish Shah

Meanwhile in New Delhi, Jeetinder Sandhu quietly launched limited edition rainbow brogues. The all-leather multi-coloured shoes, complete with rounded toe, a curve to the arch and a higher heel than usual, interplays handcrafted textures of snake, patent and soft leather. “I am Sikh and identify as gay. I wanted to create a shoe style that came from a place of genuine representation which spoke of who I am, and of proud queerness, even if worn by an ally. When we wear symbols of positivity [rainbow], it can become part of us assuming agency and spark joy,” the 31-year-old designer explains.

Founded in 2013, Sandhu’s bespoke shoe brand celebrates individuality, and has been a hit within the queer community. “Women order flats, men want chunky shoes and drag queens go for the heels. Everybody is welcome.”

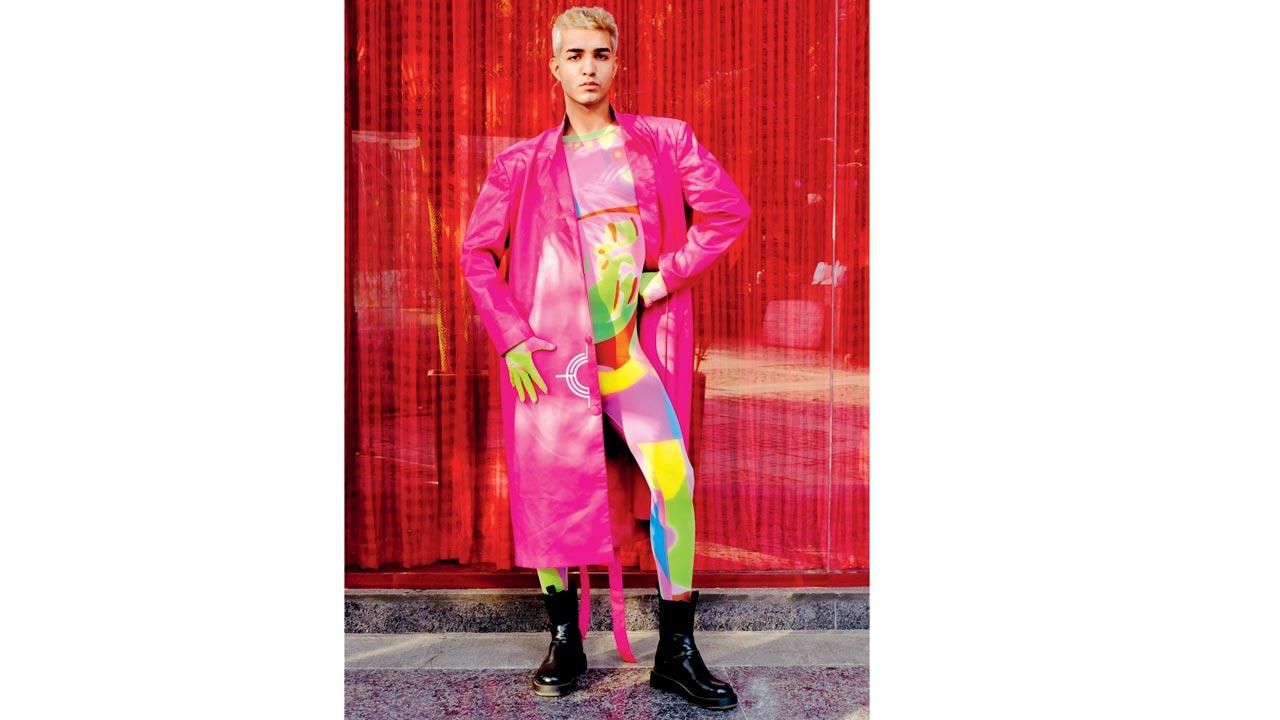

Teamed with an oversized trench, the “porn” artwork on the bodysuit is “an ode to the orgasm and symbolises liberation,” says the Akshay Sharma of Vulgar label

Teamed with an oversized trench, the “porn” artwork on the bodysuit is “an ode to the orgasm and symbolises liberation,” says the Akshay Sharma of Vulgar label

While lesbian and gay subversive fashion including the hipster staples of plaid flannels, red-wing work boots and rolled-up Levi’s skinny jeans, gained mainstream ubiquity later, it was colours that became a beacon to LGBTQIA+ people worldwide. In Don We Now Our Gay: Gay Men’s Dress in the Twentieth Century, author Shaun Cole explores how closeted gay persons have historically used bright colours to signal their homosexuality to each other. From Oscar Wilde popularising wearing a green carnation in the lapel buttonhole as a gay symbol in the late 1800s, through to pointy suede shoes.

Akshay Sharma

Akshay Sharma

In the inter-war years, particularly in New York City, red neckties did the job. At the turn of the 20th century, white gloves and pinkie rings did it. For a while, light blue socks became a symbol of homosexuality in England; yellow socks in Australia; and in France, it was the green cravat. Greek poet Sappho who lived on the island of Lesbos, referenced violets in her poems creating associations for female love. The violet flower, in addition to lavender, remains firmly in the pantheon of queer symbols.

The late American textile artist, drag queen and gay rights activist Gilbert Baker designed the original Rainbow or Pride flag in 1978, which came to be associated with LGBTQ+ groups all over the world. Pic/Getty Images

The late American textile artist, drag queen and gay rights activist Gilbert Baker designed the original Rainbow or Pride flag in 1978, which came to be associated with LGBTQ+ groups all over the world. Pic/Getty Images

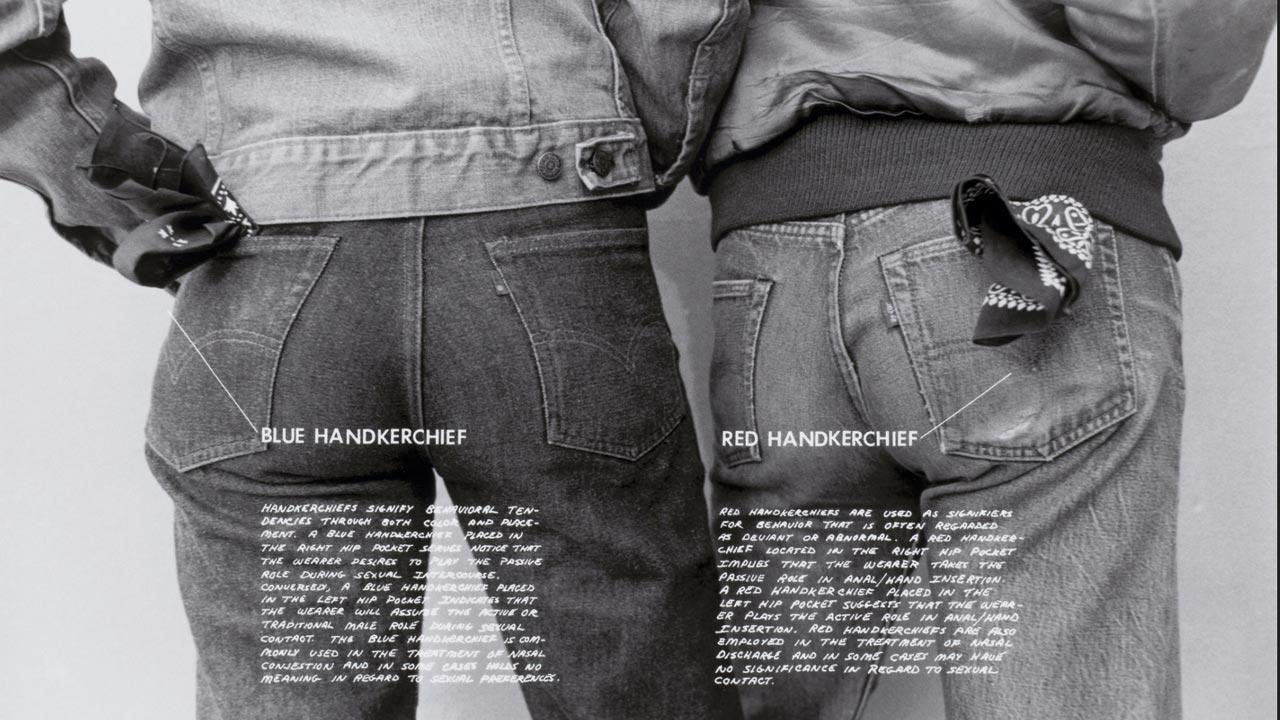

Hal Fischer’s photo series titled, Gay Semiotics (1977) deciphers a variety of handkerchief codes featuring two sets of male buttocks, each clad in form-fitting Levi’s. One sports a blue bandana in the left back pocket, which according to the accompanying text, “indicates that the wearer will assume the active and traditional role during sexual contact”. The other has a red bandana in the right back pocket implying that “the wearer takes a passive role in anal/ hand insertion”.

An image from Gay Semiotics (1977) by Hal Fischer featuring the blue handkerchief and red handkerchief codes used to denote “top” and “bottom” sexual preferences in the 1970s

An image from Gay Semiotics (1977) by Hal Fischer featuring the blue handkerchief and red handkerchief codes used to denote “top” and “bottom” sexual preferences in the 1970s

The conversation, of course, is much larger than anything that could fit into one Sunday read. It is easier to gayly analyse dopamine dressing as a trend, than it is to view the complicated performance of queerness from the prism of colours worn with the intention to project and protect.

Anvita Sharma’s label Two Point Two advocates gender-neutral expressions through cuts and colours. “People need to be able to wear whatever they want to in order to express themselves without judgement and association with their sexual preferences.”

Anvita Sharma’s label Two Point Two advocates gender-neutral expressions through cuts and colours. “People need to be able to wear whatever they want to in order to express themselves without judgement and association with their sexual preferences.”

Vulgar was founded in 2021 by Akshay Sharma to explicitly express his desire to mess around with social notions of gender and sexuality perverted by the dominant import of man and woman, heterosexual and homosexual. “The term ‘vulgar’ regulates a moral conduct that is acceptable by a society. I was quite flamboyant in college and wore makeup, but because I was born a man, my choices were perceived as vulgar!” Sharma, 26, says, professing a love for dresses and often tries on new styles, as “I see myself as a customer”. “I identify as queer but refrain from [using] rainbow colours. I’d rather provide an extra bit of character [to my garments] in my own way.”

Anvita Sharma

Anvita Sharma

Sharma’s debut collection, Intellectual Punks, trespassed the parameters of colour-coded gender representation of “blue for boys” and “pink for girls”. Its sartorial style put a homoerotic spin on clubbing energy, embracing the body with skin-tight “porn” bodysuits, bestseller slit jersey dresses and jumpsuits, leather corset tops, thongs (with and without front pouches), feminist gloves, and slogan T-shirts emblazoned with phrases: “Equality is Orgasmic” and “Hey Sexist”. Sharma describes his upcoming collection, Libertarian Movement, as “even more unhinged”. “We don’t do things subtly. When a political debate seems problematic, we let our clothes do the talking.”

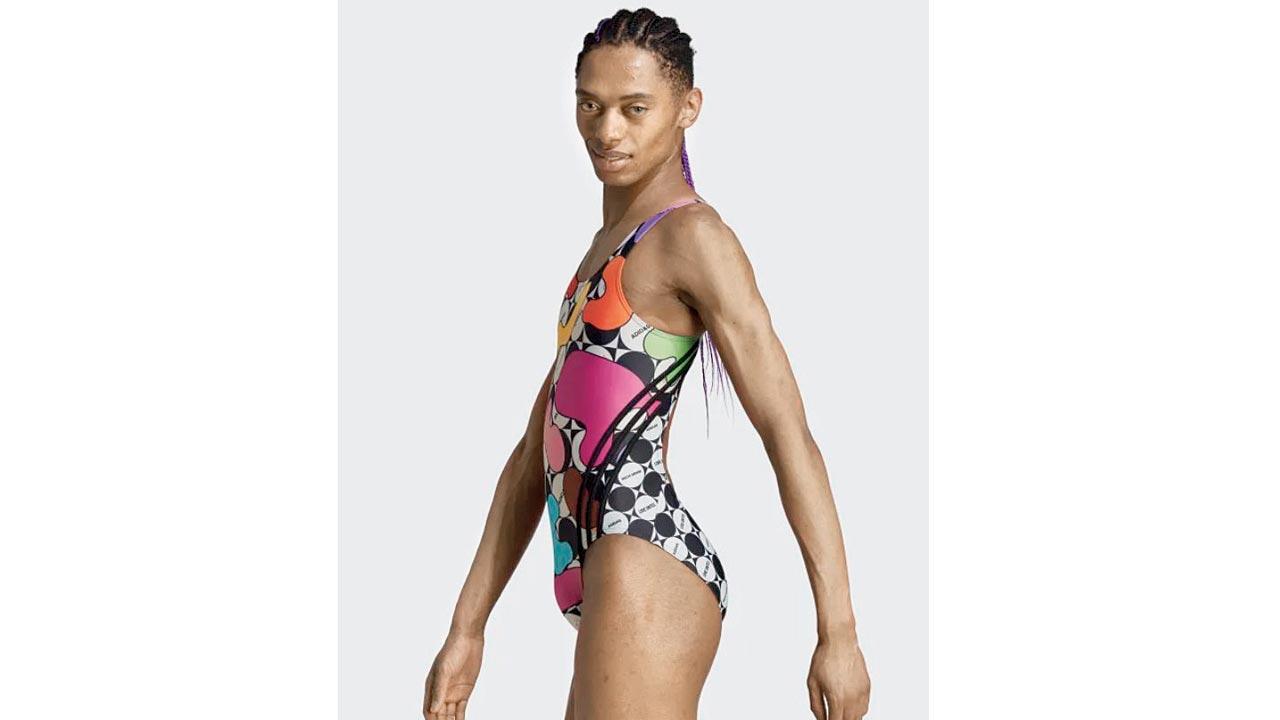

The adidas x Rich Mnisi Pride campaign instantly fell into a sex and gender debate for featuring a seemingly male-presenting model to advertise its female swimsuits, categorised under the women’s sportswear section on the website. “They could have at least said the suit is ‘unisex’ but they didn’t because it is about erasing women. Ever wondered why we hardly see this go the other way? Women’s swimsuits aren’t accessorised with a bulge,” American competitive swimmer, Riley Gaines, tweeted

The adidas x Rich Mnisi Pride campaign instantly fell into a sex and gender debate for featuring a seemingly male-presenting model to advertise its female swimsuits, categorised under the women’s sportswear section on the website. “They could have at least said the suit is ‘unisex’ but they didn’t because it is about erasing women. Ever wondered why we hardly see this go the other way? Women’s swimsuits aren’t accessorised with a bulge,” American competitive swimmer, Riley Gaines, tweeted

When Target was targeted

Big box US retailer Target faced criticism for its Pride collection launched last month. Among the items angering customers were T-shirts and baby onesies that read, ¡Bien Proud!, children’s books about transgender issues and gender fluidity, and “tuck-friendly swimsuit” (extra material for the crotch area for individuals who want to conceal their genitals) that social media falsely alleged was made in kids’ sizes. Amid the backlash, the retailer reportedly pulled some “controversial” items off the rack and moved Pride displays away from the storefront in certain markets.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!