India’s multi-age mixed-ability alternative schools are few, but fitting retorts to the unjust mainstream institutions premised solely on the idea of passing exams

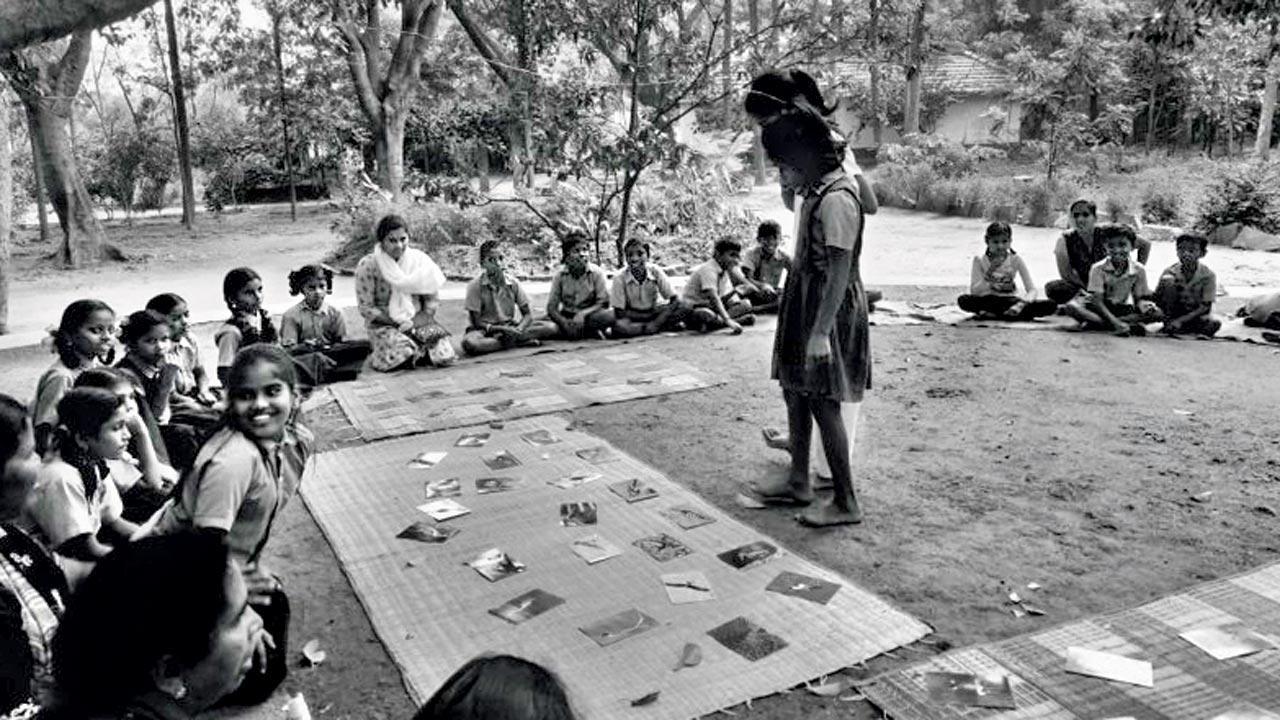

A workshop on bird life with children from the nearby Government Primary School, 2019, in Silvepura. Pics Courtesy/Jyoti Sah

![]() The coincidence was beautiful, rather educational. Two new books, published by Orient BlackSwan, on true joys of alternative out-of-the-box school education sparked a vivid memory of Hoshangabad, recently renamed Narmadapuram, for me. The pilgrim town, located on the southern bank of the Narmada river flowing through Madhya Pradesh, holds critical importance for the Narmada Parikramavasis. It’s an avenue to visit one of India’s sacred rivers; it’s a point of convergence and therefore, presents a rather sorry congested picture of pilgrims who bathe, wash clothes, clean utensils, store water, and generally throw flowers and other pollutants into the celebrated Sethanighat. It was deeply painful to witness Narmada’s pollution carried out in the name of rituals. Hoshangabad made me wonder as to why Indian pilgrims drown their formative civic classroom lessons in community spaces.

The coincidence was beautiful, rather educational. Two new books, published by Orient BlackSwan, on true joys of alternative out-of-the-box school education sparked a vivid memory of Hoshangabad, recently renamed Narmadapuram, for me. The pilgrim town, located on the southern bank of the Narmada river flowing through Madhya Pradesh, holds critical importance for the Narmada Parikramavasis. It’s an avenue to visit one of India’s sacred rivers; it’s a point of convergence and therefore, presents a rather sorry congested picture of pilgrims who bathe, wash clothes, clean utensils, store water, and generally throw flowers and other pollutants into the celebrated Sethanighat. It was deeply painful to witness Narmada’s pollution carried out in the name of rituals. Hoshangabad made me wonder as to why Indian pilgrims drown their formative civic classroom lessons in community spaces.

ADVERTISEMENT

But the same Hoshangabad came alive as a test case of an internationally acclaimed experiment-based science education programme highlighted in two new books. The first, Education, Teaching, and Learning, delineates milestone departures in the discipline of Education in India, much like the Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme (HSTP) launched in 16 government-run middle schools of Hoshangabad district in 1970. The second book, Un/Common Schooling, focuses on alternative schools founded in India’s remote and marginalised parts, which includes a chapter on the synergy between the Eklavya society and the Madhya Pradesh government in remapping of the existing science curriculum. Both books underline the socio-cultural dimension of science education. They elaborate on multiple field-tests and revisions of the science curriculum spanning over three decades. While writing experiment-based science books forms the core of the project, the HSTP story is more about the joys of collective learning, the idea of treating student-teacher community as a laboratory and training science teachers to be fellow travellers beyond classrooms.

A class being conducted under the trees at Sita School, pioneered by Jane Sahi, in Silvepura in Karnataka, 1976

A class being conducted under the trees at Sita School, pioneered by Jane Sahi, in Silvepura in Karnataka, 1976

Both books would have benefitted by way of colourful photographs of unconventional rural schools—some under the sky or amidst wilderness. The featured schools immensely contributed to nation building, despite the lack of basic conveniences. Photos can best underscore the minimalism of these ventures.

Also read: Gadar 2: Ameesha Patel thanks Anil Sharma for Sakeena-Tara love story amid feud

Un/Common Schooling has basic black and white photo footage of children’s school projects, vigyan melas, morning assemblies, leaf art, parents’ meeting in tribal belts, school gardens etc. But Education, Teaching, and Learning is totally devoid of colour. Orient BlackSwan will serve its own interests by aiding the 380-page tome with photo-archival material in the second edition. The HSTP in particular will spring to life in both the books, considering the Narmada maiyya backdrop in many curricular activities.

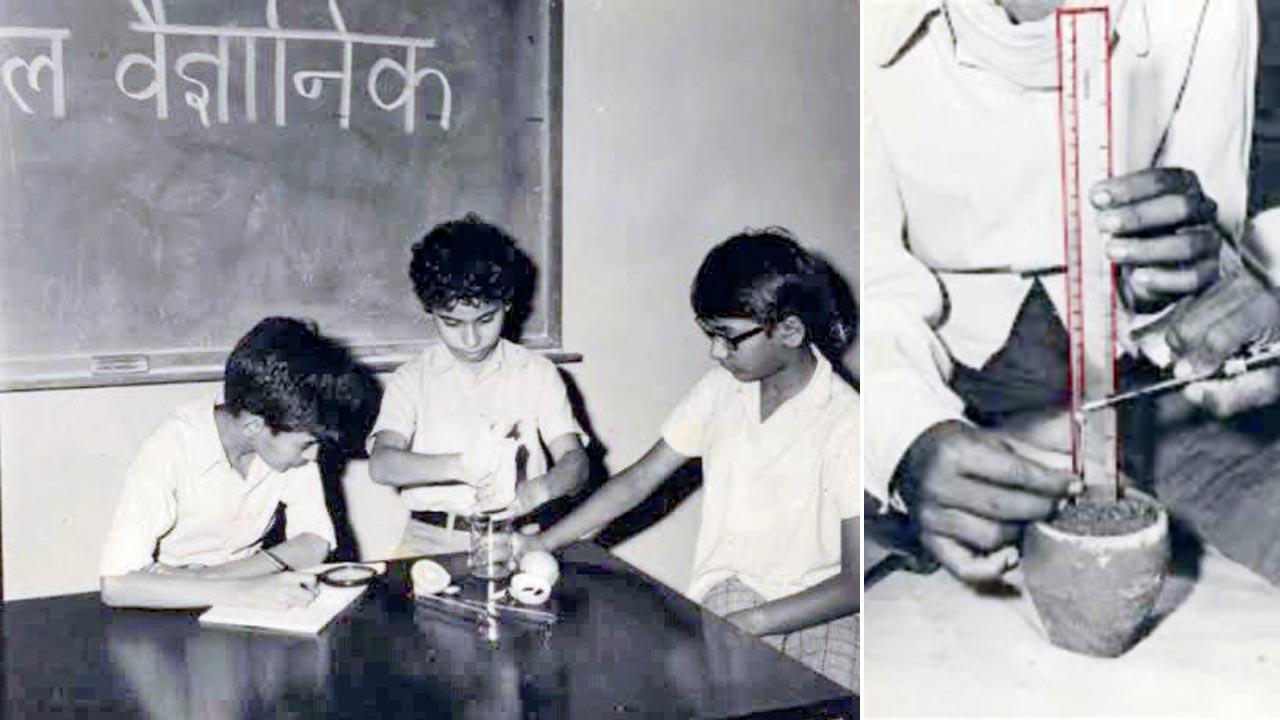

The experiment-based Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme (HSTP), conducted across schools in Hoshangabad in the 1970s

The experiment-based Hoshangabad Science Teaching Programme (HSTP), conducted across schools in Hoshangabad in the 1970s

The HSTP experiment, earlier documented in books like Jash-e-Taleem, indeed encompassed a vast population because it encouraged teachers’ peer forums and balvaigyaniks to learn concepts in the “open”, guided by updated reference kits. The impact of fertilizers on soil types had to studied in an open-to-sky lab. Textbooks were supplemented with fillable workbooks, which called for learning by doing. Kharif and rabi season field trips were planned to learn about crop health. Students and teachers were not seated hierarchically in a classroom to learn the functioning of a lightbulb, but they were democratically spread out in a workshop hall. Questions on physics or biology could be asked aloud and without hesitation, an empowerment a few hyped schools grant.

As the HSTP experiment caught on, the MP government in 1995 evolved a framework for reforming the primary school curriculum. Eklavya, UNICEF and State Council of Education Research and Training presented their alternatives, which ultimately led to a merged state curricula, called the Seekhna Sikhana Package. While this package later faced political opposition and was overturned by the government, the book Un/Common Schooling opens the readers’ eyes to Eklavya’s attempts (some successful) to infuse a spirit of enquiry in the textbook-centric pedagogy.

The Eklavya institute insider Rashmi Paliwal—till date associated with educational publications and courses—has honestly recounted the journey in the book; acknowledging the failures and celebrating the life stories of students from low-income households, especially those hailing from Harda and Shahpur blocks, who gained confidence from science classes. The HSTP made science accessible and experiential; rendering tuitions unnecessary in poor students’ lives.

The book Education, Teaching, and Learning: Discourses, Cultures, Conversations captures the HSTP in the words of Sadhna Saxena, a Delhi University professor, who was part of the volunteer-driven rural development organisation Kishore Bharati in MP. Saxena recounts the herculean efforts to reach Palia Pipariya, Bankhedi, and Itarasi, which were not well-connected on bus or rail transport route in the 1970s. The HSTP team literally walked miles—as opposed to using jeeps, as that would distance villagers—to reach their target audience.

Saxena evokes the pre-telecom era India when booking a trunk call from Hoshangabad to Bhopal consumed a day-long effort. Similarly, the design, making and printing of new textbooks was painstaking in the pre-photocopy period. Cover pages of science textbooks were reconceptualised, so that stereotypes of scientists in lab coats could be busted. Lecture-based teachers’ orientations were also remodelled. Informal “under a tree” training was chosen; local vaids and experts on flora and fauna were free to join the exploration. Saxena remembers the vital role played by the residential hostel of Hoshangabad where resource persons from Delhi and Mumbai stayed with the nimna aur uccha shreni (lower and upper grade teachers) shikshaks. It was an opportunity for urban minds to discover the talented kasba teachers, and to realise the feudal hierarchy in the Indian education system, which violates teachers on the basis of caste, gender and ethnic background. The book is a timely resource for policymakers and sociologists alike, especially as India embraces a more engaging inclusive New Education Policy.

Sadhna Saxena asks a pertinent question about the replicability of the HSTP experiment in present-day economically liberalised India. The point also applies to other experiments featured in both the books—the Sita School pioneered by Jane Sahi in Silvepura, Vikasana in Doddakallasandra founded by Malathi M C, Kanavu school/commune for Wayanad’s adivasi children reared by KJ Baby and Shirly Joseph. Were these unconventional schools possible only in the pre-Internet era? Saxena feels the ’70s offered a social climate for outside agencies and independent educators to contribute to a government system. The space for informal exchanges has shrunk now. Infact, one of the reasons for closure of HSTP—yet undocumented—is the conflict with the government.

It is rewarding to note that Un/Common Schooling honourably mentions educational experiments in Western India too, notably Madam Montessori’s informal education idea first executed in Gujarat by Gijubha Badheka and then Padma Bhushan Tarabai Modak in Dahanu, Maharashtra. Tarabai Modak and Anutai Wagh’s endeavours in reducing the cost of early education today reap fruits in Dahanu’s Kosbad hill where Nutan Bal Shikshan Sangh’s school serves adivasi children as a guiding institution.

India conceded the Right to Education in 2009. Admittedly, it was long overdue. The delay was also symbolic of an unjust, divisive and undemocratic system of education rooted in a colonial ethos. Against such a backdrop, stories from alternative schools are a ray of hope; and the one from Hoshangabad certainly affirms the belief in team chemistry.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at sumedha.raikar@mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!