Three designers from different backgrounds discuss the enduring appeal of Indo-Western attire, revealing how the women who wear it are the true architects of its influence

Kareena Kapoor Khan wears Masaba Gupta’s gold foil print jacket with a saree-drape skirt

The other day, designer Narendra Kumar (Nari for friends) ran into Anita Dongre at the airport. They go way back to the mid-1990s when they collaborated on the launch of AND, a Western wear line introducing pantsuits, skirt-suits and shirts, coinciding with the growing trend of women in the workforce. “Anita’s vision was clear—to create garments that resonated with this societal shift and evolving professional landscape,” Nari recalls. “I helped shape the campaign, branding, and brand name.”

The other day, designer Narendra Kumar (Nari for friends) ran into Anita Dongre at the airport. They go way back to the mid-1990s when they collaborated on the launch of AND, a Western wear line introducing pantsuits, skirt-suits and shirts, coinciding with the growing trend of women in the workforce. “Anita’s vision was clear—to create garments that resonated with this societal shift and evolving professional landscape,” Nari recalls. “I helped shape the campaign, branding, and brand name.”

Nearly three decades later, Nari notices a surge in the number of women adeptly balancing career and family routine, drawn to a fusion style blending South Asian and Western influences. Co-ord sets and dresses with playful hemlines guide their preferences. Or, they may fancy a tunic featuring cuff details like tie-ups, paired with slim-cut trousers. “My 90-year-old mother, who typically wears the salwar-kameez, recently showed interest in wearing a co-ord set!” he chuckles. “This reflects a quiet but clear shift in attitude. Women, regardless of location, are becoming more educated and well-travelled. The rising influence of modern secular women from tier-2 and 3 cities highlights a global perspective, amplified by social media’s homogenising on fashion.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Lakshmi Rana models Inca’s tie-dye saree-gown; Tamiska’s Black & White Story line features a cowl neck kaftan with a tie-up detail at the waist; Masaba Gupta’s gold foil print, introduced in 2015, remains a perennial bestseller

Lakshmi Rana models Inca’s tie-dye saree-gown; Tamiska’s Black & White Story line features a cowl neck kaftan with a tie-up detail at the waist; Masaba Gupta’s gold foil print, introduced in 2015, remains a perennial bestseller

In India’s fashion landscape, a curious distinction exists between mass-market Western brands like Zara or Vero Moda—considered “fashion brands”— and ethnic brands like Soch or Biba, which do not fall into the same category. Despite 65 per cent of the country’s population preferring ethnic wear, this disparity stems from limited options for style, fit and value clothing. “Tamiska was born to bridge this gap,” Nari explains, referring to the brand of affordable semi-ethnic silhouettes with refined tailoring that he co-founded and now leads as creative director.

In fashion history, trends typically require time to establish themselves. Indo-Western clothing, known by various monikers like “India modern” or “diffusion”, has seen numerous transformations over time. “Just a few years ago, the term ‘Indo-Western’ lacked the ‘cool girl factor’,” reflects Masaba Gupta, a designer often attributed with reigniting interest in fusion wear.

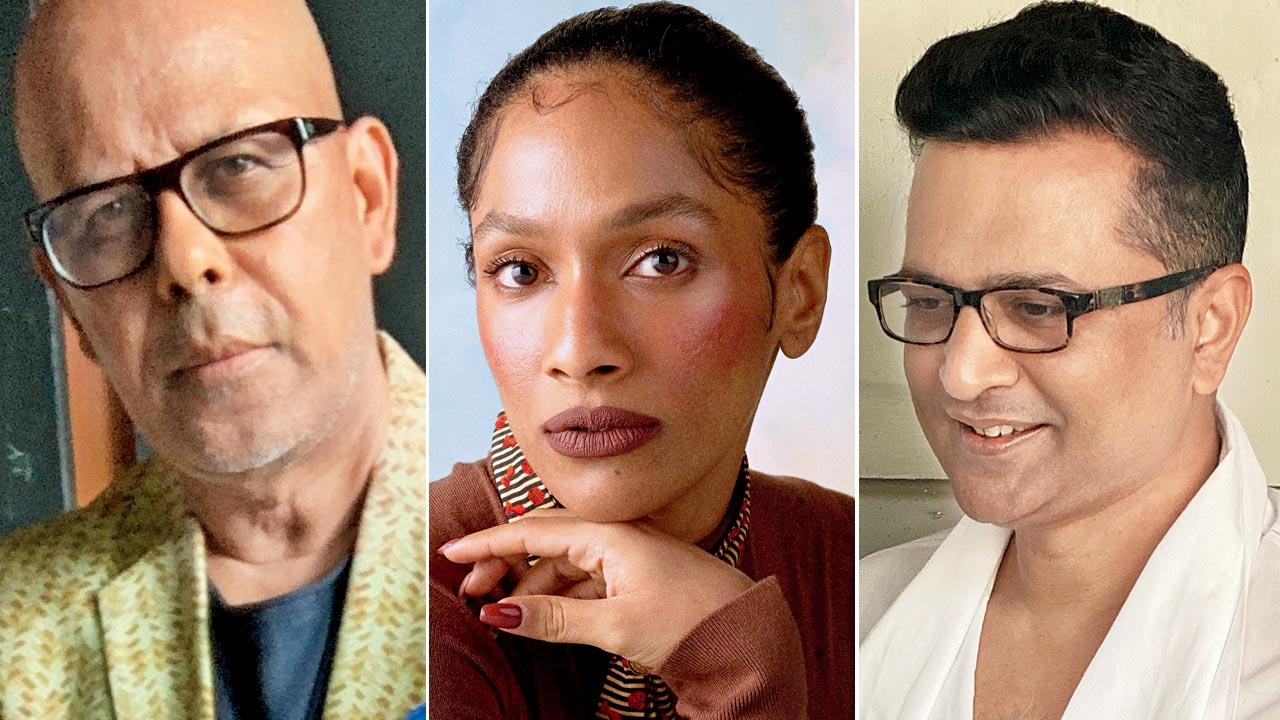

Narendra Kumar; Masaba Gupta and Amit Hansraj

Narendra Kumar; Masaba Gupta and Amit Hansraj

The fusion style has deep historical roots, tracing back to the Portuguese occupation of Goa, where traditional attire faced suppression until as recently as 1961. Despite this cultural upheaval, Goan residents ingeniously blended elements of Western fashion with indigenous styles. This fusion, often compared to the Stockholm syndrome, gave rise to a unique attire featuring waistcoats and boots worn with sarees. Late designer Wendell Rodricks credited Goa as the birthplace of the first Indo-Western clothing styles. Subsequently, the trend evolved with various reiterations, including Monisha Jaising’s modern versions of the traditional kurta with short and embellished kurtis, and Ritu Kumar’s exploration of paisley prints on Western silhouettes. These interventions played an important role in breaking down stereotypes and promoting cultural understanding.

Masaba’s debut collection at the age of 19 in 2009 marked a vibe shift. Preferring terms like “fusion” or “global” for her design aesthetic, she remembers the uncertainty around introducing “bright and shiny foil prints” on Western shapes like dresses. “It unexpectedly became a bestseller,” Masaba adds, “transforming the brand’s fortunes and defining our signature style.”

According to Masaba, their true customer is not the celebrity but an everyday woman reshaping her relationship with fashion. “The styles could be modern—kaftan, maxis, co-ord sets—but they still carry a distinct Indian imprint through colours and motifs. These choices reflect a broader cultural change in how she wants to make herself visible, expressing her identity through fashion, proudly proclaiming: ‘Hey! I don’t give a damn, I want to wear India on my sleeve’.”

In today’s workplace, the default attire for a working woman is no longer an A-line kurta with leggings; a dress serves just as well. “The demand for clothing with a modern flair and elegance is radically shaping attitudes and markets. Take necklines, for instance. We used to limit them to 9 inches—anything beyond that was too daring. But today, women are comfortable with 11-inch necklines,” explains Masaba.

Indian fashion is experiencing a renaissance of sorts, a vibrant celebration of diversity and personal expression. Masaba hopes to tap into this newfound mood of inspiration and aspiration with the launch of Kinda Kooture on May 28. The collection represents a mix of her brand’s blockbuster prints and shapes, such as cinched sarees or lungis paired with dinner jackets—that to her, is proper Indo-western fusion. Positioned between occasion wear and ready-to-wear, she believes it meets the evolving preferences of women who are discovering the versatility of traditional Indian silhouettes.

The timeless charm of the saree and salwar-kameez extends beyond mere aesthetics, offering both practicality and the chance to mask physical insecurities, such as arms and hips. “Cultural modesty is also a factor; women prefer styles that maintain discretion, avoiding ensembles that expose the crotch, for instance,” explains Amit Hansraj whose label Inca channels the free-spirited vibe of the 1970s.

In just four years since its launch in 2020, Inca has dressed women of all body types. The brand offers a range of options including kurtas with built-in hoodies, and tuxedo shirt-inspired cuffs, kaftan dresses with a nod to saree draping, and trousers with drawstrings or elastic waistbands. Amit’s decision to anchor his designs around familiar silhouettes reflects his understanding of his clients, which comprises professionals like architects and journalists. “They prefer clothes that offer understated luxury and comfort, rather than couture or casual Western garments.”

With his background in fashion merchandiser, Amit stresses that cultural fusion transcends trends, resonating not only within Indian community but also with Indophiles, expats and reaching a global audience. “Choosing to dress in clothes that celebrate cultural heritage in contemporary fashion reflects a certain intelligence and confidence,” Amit believes.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!