So my amnesic cabbie & I couldn’t figure why India’s wounded metropolis was quiet, leading up to Dec 6, 2022!

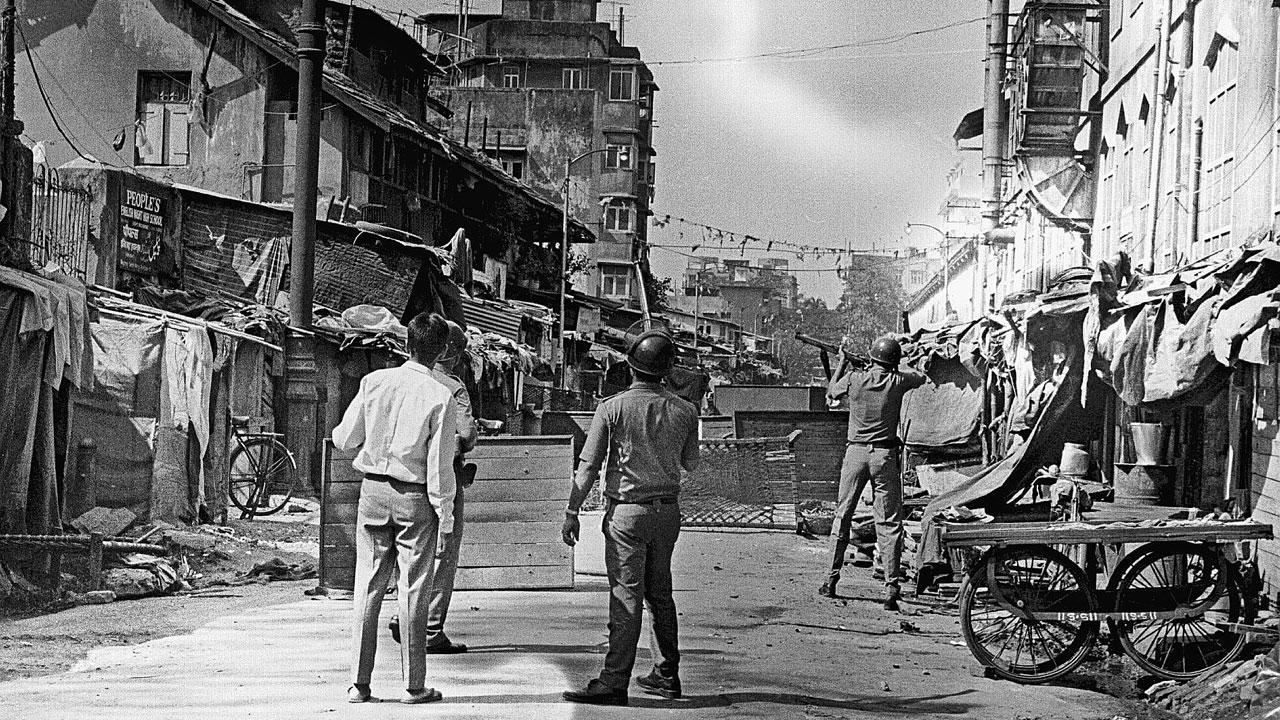

A photo of Mumbai during the riots on December 6, 1992

ADVERTISEMENT

As bombastic Bollywood plots go, the one in Rohit Shetty’s blockbuster, Sooryavanshi (2021)—about sleeper (terror) cells, that spring back into action, decades after remaining incognito in the city, living with fake identities, and weapons/explosives buried under the earth, since 1993 Bombay bomb blasts—isn’t fantastical after all.

Soon after ’93 blasts, Bombay police did swiftly recover 2000+ kg of RDX, 1000+ kg of gelatine, 63 AK56s—from the same cache that a rifle made it to Sanjay Dutt’s home. It’s fair to assume the cops couldn’t have located all the hidden auzaar at one go.

The consignment was brought in by the underworld. Knowing the blasts would trigger another round of communal riots in Bombay. Only that no riot took place.

Indeed, the then Maharashtra CM Sharad Pawar got on national TV, to list locations attacked in the blasts—falsely including a mosque among them. This was to avoid an instant religious overtone to the bombings.

Seasoned, solid crime reporter Jitendra Dixit—in his fine book, Bombay After Ayodhya, an essential primer to understand contemporary Mumbai, from a news lens—argues that Bombay has often reverberated over events occurring outside its perimeter.

Also Read: Mumbai: NCP chief Sharad Pawar receives death threat

Fatwa against Satanic Verses in Tehran, oppression against Rohingyas in Myanmar, 2002 riots in Gujarat, Israel-Palestine conflict (a Jewish centre was attacked during 26/11)…

The cover of Jitendra Dixit’s Bombay After Ayodhya: A City in Flux

On top, of course, is the destruction of Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, on Dec 6, 1992. My only practical memory of it as a kid in Delhi is that certain inter-city trains had been cancelled. Surely the whole country was affected.

None close to Bombay—where, according to Pawar’s own memoir, 2,000 Indians were killed (official estimate is 900; 2,000 injured)—under the watch of CM Sudhakarrao Naik, from the Congress, who was rightly sacked thence.

Shiv Sena’s Bal Thackeray, on the other hand, achieved national fame, as a Hindu Hriday Samrat of sorts. His party had been practicing a heady mix of religion into politics since the late ’80s.

The author Dixit himself, who lived in a chawl around Mohd Ali Road, was bang in the middle of the Dec 6 riots, that quietened, and then restarted, Jan 6, 1993.

The latter apparently instigated by one, Jaseem, Dixit’s enraged friend from school, who, along with two others, killed off porters at a transport company in Dongri. Both instalment of riots, seemingly died down on its own, in a week or so.

As if a city so adept in the art of living (together), had practically lost it, over a momentary lapse of reason. And then woken up from the frightening night, pretending nothing had happened. Like it is after a monsoonal deluge—so what, look up, clear skies, get to work.

About two lakh people, as per Dixit, left Bombay. Given Hindu-Muslim mistrust at its peak, communally exclusive ghettos came up in farther corners—Mira Road, Mumbra, Kausa, Bhayander…

There is also the political paradox of a party creating conditions for fear and insecurity, and planting oneself then as the only possible saviour from its resultant wrath. Sena came to power in 1995. Revenge is a vote bank. Stockholm syndrome was complete.

Surely the ’93 blasts, partly in reaction to ’92 riots, would’ve cemented the deal for Sena. What did it do to the Mumbai underworld, chiefly run by Dawood, Rajan, besides, Gawli, Naik, Salem, as competing crime syndicates called ‘companies’? They were the godless mafia. As against gangsters.

The former can get away with anything, the latter can’t. Also, if you’re neither friends nor enemies with the don, they usually let you be.

With Dawood/underworld graduating to terrorism in ’93— and the world’s first such terror attack—you’d think none of the rules above would apply. True.

Yet, the most number of day-light shootouts, murders—including high-profile ones, Gulshan Kumar, Mukesh Duggal, etc—happened only in late ’90s. This could be the underworld’s desperate statement that they still count.

I guess the crippling of Bombay mafia also had to do with 1991 economic reforms—the other moment that transformed India—making smuggling of bullion, foreign goods, etc, redundant. Firangi products became local. Customs duties rationalised, stock market skyrocketed, legit real-estate investments shot up…

What did that leave rival ‘companies’ with—besides placing extortion calls? There was Bombay’s prosperous, colourful night-life, yes. But that was getting destroyed by moral parenting of the Sena, to start with.

In competition, a home minister with a more rural mindset, R R Patil, killed the city’s 1,250 all-night, dance-bars. By then, it was the bratty cops—OG ‘bhais’ of Bombay, overtly empowered to take on the mafia—who needed to be tamed. They apparently profited most from dance-bars.

Lack of space for a home anyway left little for a Bombayite to call, life—his name changed to Mumbaikar after 1996, notwithstanding. Night-life progressively disappeared too; mostly over security concerns, apparently.

Enough water has flowed under the bridge since: can’t tell who’s Sena, or where’s Dawood anymore. But there certainly is/was a Bombay, before & after ’92.

Driving through unusually deserted Mumbai streets, same day, exactly 30 years later, my cabbie and I wondered, “Itna sannata kyun hai, bhai?” We thought of many reasons: Ambedkar death anniversary, maybe, end of year, obscure festival holiday, etc. ‘Dec 6’ didn’t once occur to us.

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!