With Rustom Baug just hitting a century, we revisit other Parsi enclaves founded by the community’s visionaries

Restored Murzban Colony buildings at Bombay Central

It’s a privilege I haven’t had. Of living in a baug, that quaint yet quintessential bastion of Parsidom, whose clusters house over half of the approximately 37,000 members of my community left in the city their ancestors brilliantly built.

It’s a privilege I haven’t had. Of living in a baug, that quaint yet quintessential bastion of Parsidom, whose clusters house over half of the approximately 37,000 members of my community left in the city their ancestors brilliantly built.

ADVERTISEMENT

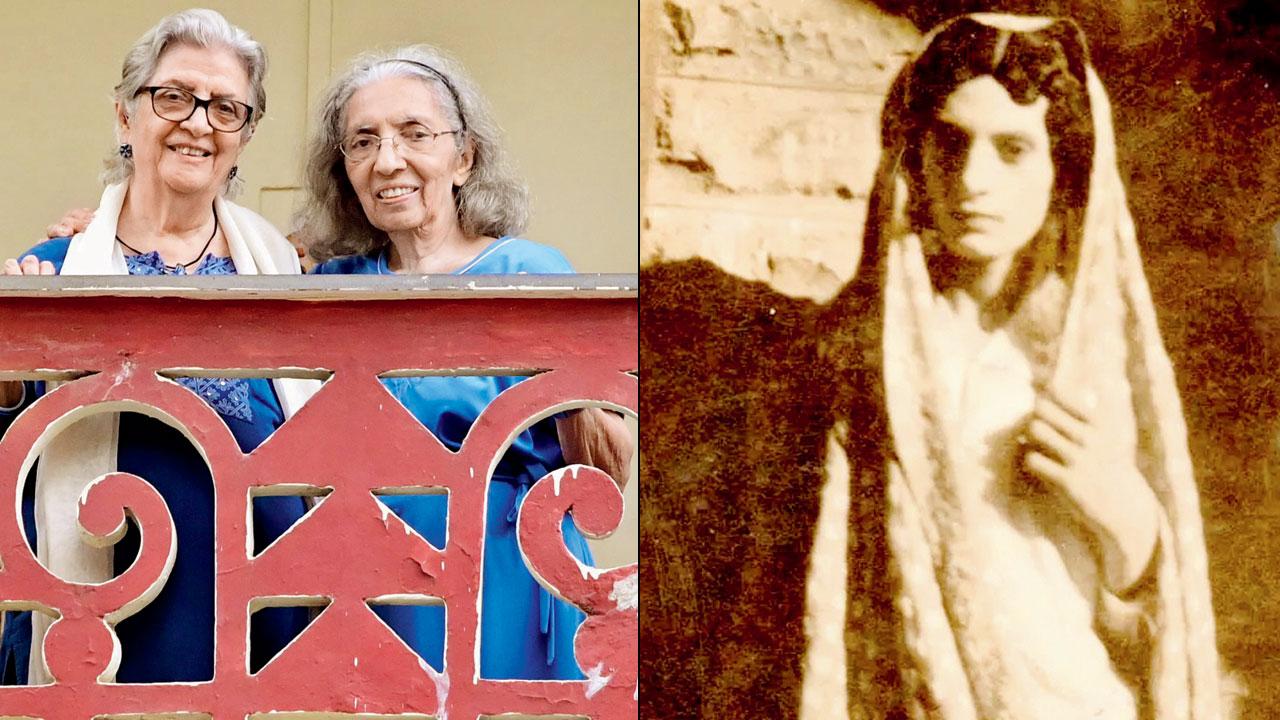

And yet, there’s always a connect somewhere for everyone. Mine is with Bombay’s sole unwalled baug—Dadar Parsi Colony—where my parents grew up. A bunch of cousins continue to occupy apartments bordering the commemorative bust of Mancherji Joshi, my maternal great-granduncle and founder of this leafy-laned colony.

Oases of calm, sheltering havens amid the chaos of ugly towers, baugs extend comfort, camaraderie and carrom (think Munnabhai, movie buffs). That thousands upon thousands of Parsis and Iranis for over a century enjoy the affordable accommodation and serenity of baugs is a boon we owe visionary philanthropists like the Wadias.

Zareen Engineer and Sooni Davar at their grandfather Mancherji Joshi’s statue in Dadar

From Andheri to Agripada to Colaba, colonies continue to hold close grateful generations. Not unlike some of their eccentric inhabitants, each bears a quirky qualifier. Cusrow Baug on Colaba Causeway, for instance, boasts Claude Batley-designed blocks lettered all the way from A to U. Baffling to consider why I, L, N and O are curiously absent. When the shutters were downed on the last original shop fronting this baug since these sprawling rowed blocks rose in 1934, I wrote a story on it. Heeding and feeding my genes? That was Aga Brothers Dairy Farm, selling the best Frankie rolls.

Rustom Baug on Victoria Road in Byculla just turned a 100 years old. The loveliest rain tree on its central lawn shades children chasing butterflies, squirrels sipping water from troughs for them and hooting night owls. Murmurs from senior citizens claim a white-clad bearded horseman strode through, a rumour fairly fuelled by old graves on the premises. While these may or may not have been Armenian, five Armenian-inscribed tombstones from 1767, at 9 Victoria Road, are confirmed by Mesrovb Jacob Seth in his book, Armenians in India.

Rati Wadia and Dinoo Damania in Shapur Baug; Wadia’s father in a saree for a 1949 colony play

But the biggies—Cusrow Baug, Rustom Baug, Jer Baug, Dadar Parsi Colony and Malcolm Baug—present part of the picture. Before writing local history columns, I discovered the delightful denizens of Navroze Baug, Shapur Baug, Wadia Baug, Khareghat Colony, Gamadia Colony, Captain Colony and Cama Park, while researching books on the history of Parsi theatre and the wonderful whimsies of Parsi Gujarati phrases, the latter in collaboration with my friend Sooni Taraporevala.

Way ahead of Jiyo Parsi campaigns exhorting us to birth better scores of babies, countless couples met and married within these tight-knit zones. Like Dolly and Bomi Dotiwala of Navroze Baug in Lalbaug. The singing star pair cherished their association with writer-director Adi Marzban. As kids, Dolly Kateli of M Block and Bomi of N travelled together from the colony to their schools. The tram trip allowed ample time for exchanged love notes.

Dolly first went onstage in Navroze Baug, acting as a local tarkariwali hawking vegetables. “I was called the colony Dev Anand, my hair puffed exactly the way he wore his,” Bomi said. “People gathered on balconies to watch shows we ‘staged’ in the space between our colony’s M and N buildings. My parents’ place was the changing room,” Dolly had chimed in when I interviewed them.

Detail of the ship announcing Shireen Mansion in Gamadia Colony, Tardeo

A baug whose entranceway makes me smile every single time I pass it, though nowhere as grand as the Cusrow or Rustom Baug gates, is Tardeo’s Gamadia Colony. A pair of urban legends explains the plump-sailed ship motif underlining the Deco lettering announcing Shireen Mansion. An elderly lady, whose parents were early tenants in the 1938-erected building, told me about their then landlord Burjorji Bhesania. His trade involved transporting grass bales between Bombay’s seven islands in boats—therefore the enduring nautical image. The ship could pertain to the larger prevailing Art Deco trend that pre-Independence architects toyed with, to break away from colonial themes. Ships, trains and planes, symbolising speed and the surge to hit horizons beyond the Arabian Sea, embellished exteriors.

In the week of making Mori Road my beat, came the story of an agiary which renders doubly venerated the Mahim mile around St Michael’s Church. Residents beyond Contractor Baug in the neighbourhood revere the aura cast by the Soonawala Agiary. This adoration is traced to Aden, the port once thriving with large numbers of wealthy Parsi traders. An agiary erected for their worship in 1883 by the shipping magnate Cowasji Dinshaw Adenwalla was consecrated with atash (fire) of holiest Adaran grade. When the British left Yemen, Parsis there determinedly brought back the fire that nurtured them on foreign shores. Flown on a chartered Air India Boeing in 1976, the sacred flame rested awhile at Soonawala Agiary before being escorted by a special convoy on the Bombay-Poona highway, to finally glow where it does in Lonavla’s Adenwalla Agiary.

Far north in noisy Jogeshwari, Malcolm Baug offers a soothing balm when you turn into it for relief from the main road craziness. To be greeted by paths lined with cottages ringed by flowering garden patches is pure pleasure. Never tick anything except the “We will be glad to attend” box printed on invitation cards for weddings or navjotes hosted here, no matter if you travel from the other end of town.

A transformative process can hearteningly rekindle fresh energy within an enclave. It was my privilege to feature Murzban Colony after it underwent restoration. Quietly gentrifying the east Bombay Central stretch near Nair Hospital, five low-rise buildings of one-bedroom and bathroom units make up this colony, named after Muncherji Murzban, the BMC engineer who promoted housing for the poor. Located in what came to be called Lal Chimney Compound, because of a red chimney in its midst, the baug sets standards of true trusteeship.

The Garib Zarthostiona Rehethan Fund (GZRF), the Trust running Murzban Colony, worked for results creative enough to earn it the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Award in 2013, following a thorough structural revamp. Tackling the challenge of dilapidated structures, the project team fully opened, tarred and tiled roofs, repaired building shells, revived facade carvings, uncovered original balustrades, redid plastering along staircases, overhauled electrical wiring and replaced sewage pipes.

Of his unusual refurbishing assignment, architect Vikas Dilawari says, “A free hand was given, no corners cut. Like-to-like materials brought back old glory using Burma teakwood, redoing the ornamentation and cornices. Many have money. We need more such supportive patrons.”

Fortunately, Muncherji Cama had headed GZRF. Sensitive to the reality that tenants cannot afford maintaining redeveloped flats, he gave the Dadachanji, Cooper, Wadia, Mody and Talukdar Buildings a gift to remember. What Cama acknowledged as “a sacred duty” has hardly gone unappreciated. As one tenant said, “Our homes got not just a facelift but a new lease of life. The onus is on us to look after them.”

We wish more spaces could stay refreshed. Hard to imagine the vibrancy which marked 1939-built Shapur Baug, off Grant Road. Home to acclaimed dancer Astad Deboo and violinist Siloo Panthaky who played with Yehudi Menuhin, this colony is where I warmed to an epic friendship. Accompanying Rati Wadia, former Queen Mary’s principal, to her homemaker friend Dinoo Damania’s block opposite in Shapur Baug, I learnt how these octogenarians, friends from the age of two, still eat dinner together daily. “We had fun at our doorstep, with well-planned picnics, jashans, fairs, stilt-walking, roller-skating and sports. And drama!” Wadia exclaims, flourishing a sepia-browned photo of her father, Dara Vania, dressed for a woman’s role.

Shapur Baug residents hardly have a monopoly on devotion to next-door Aslaji Bhikaji Agiary. The faithful countrywide flock to this 1860s fire temple. Queues of believers bearing sandalwood sticks coil longest on certain auspicious dates, including Meher roj in the Zoroastrian calendar month.

A pit-stop at this baug gate got me chatting with Azam and Mohammad Dabir of Ezzad Cold Drink House. One of them said, “Our main customers are from Shapur Baug, stocking up daily for bread, eggs and wafers. The best customers too, the noble Parsis.”

My eyes rest on a tenderly framed Zarathushtra portrait. It has literally served as their saving grace—the prophet’s image spared these Muslim shop proprietors the savagery of 1993 riot attacks. Care in carnage. Blessings, benevolence, beatitude. The moments do add up in these benign oases in an oft brutal city.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!