How do the young view Gandhi's life and times and teachings? Visual historian Dr Sumathi Ramaswamy shares her discoveries of the Mahatma interpreted by Bombay schoolchildren's art

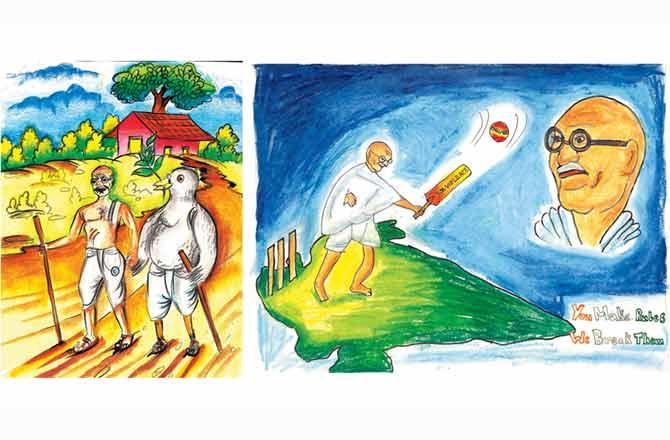

(From left) Shubham, Gandhi in My Dreams, Standard IX, GPP High School, Vile Parle, 2012. Pavitra, Untitled, Standard III, JB Vachha High School, Dadar, 2015; Pics courtesy Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya and Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai

In 1920, Gandhiji launched the epoch-turning Non-Cooperation movement in the city. To mark its centenary year, the Bombay Local History Society recently held an online public lecture by visual historian Dr Sumathi Ramaswamy, whose riveting research explores the work of city artists on the theme. Titling her talk, A Brush with Bombay's Bapu, the Professor of History and International Comparative Studies at Duke University, North Carolina, says, "Mumbai had a special place in the Mahatma's life. Not surprisingly, several scholars have explored his relationship with the city, but none considered the special attention Bombay artists, from the unknown to the famous, lavished upon the Mahatma. I took on this topic to discover what we learn about Bombay and Bapu if we move the image to the centre of our analysis."

In 1920, Gandhiji launched the epoch-turning Non-Cooperation movement in the city. To mark its centenary year, the Bombay Local History Society recently held an online public lecture by visual historian Dr Sumathi Ramaswamy, whose riveting research explores the work of city artists on the theme. Titling her talk, A Brush with Bombay's Bapu, the Professor of History and International Comparative Studies at Duke University, North Carolina, says, "Mumbai had a special place in the Mahatma's life. Not surprisingly, several scholars have explored his relationship with the city, but none considered the special attention Bombay artists, from the unknown to the famous, lavished upon the Mahatma. I took on this topic to discover what we learn about Bombay and Bapu if we move the image to the centre of our analysis."

ADVERTISEMENT

Dr Ramaswamy has published extensively on language politics, gender studies, spatial studies and the history of cartography, visual studies and the modern history of art, as well as digital humanities and the history of philanthropy. Her published works include Gandhi in the Gallery: The Art of Disobedience, The Goddess and the Nation: Mapping Mother India and Husain's Raj: Visions of Empire and Nation. She has edited Barefoot across the Nation: Maqbool Fida Husain and the Idea of India, and co-edited Empires of Vision. Among her digital curatorial projects are Going Global in Mughal India and B is for Bapu: Gandhi in the Art of the Child in Modern India.

(Left) Mansi, Gandhiji Planting a Sapling, Standard IX, Udayachal High School, Vikhroli, 2017; Devyani, Gandhiji and Kasturba, Standard X, Udayachal High School, Vikhroli, 2016

"Given that Gandhi has been the subject of much artwork by adult artists in his lifetime, this may also have been the case with child artists," she says. "The challenge is too little documentation available. There is virtually no scholarship on child art in India. Rarely are children's drawings and paintings saved or deemed worthy of preservation, let alone documentation. This makes the archive of their paintings of Gandhi in Mani Bhavan such a precious resource."

When did you first find examples of children's art repurposing Gandhi's life for our times?

As with many intellectual projects, there was a good deal of serendipity to this one. I had not been thinking about children's art, walking into Mani Bhavan in March 2016 to check out its museum for a new project on Gandhi and art. There, an old friend, Usha Thakkar, asked if I would be interested in an archival treasure. The wrong question to ask the historian (or the right one)!

She led me to a corner of the library stacked with neat newspaper-wrapped bundles. As they were opened, one by one, my interest was piqued. There were more in a back room. Absolutely hooked, I began to review these utterly charming works in detail. It took four years to produce

B is for Bapu, the digital project based on these paintings I wrote at length about.

Dr Sumathi Ramaswamy

"Drawing Gandhiji" is a pet theme in schools, mandatorily prescribed around January 30, August 15 and October 2. Do kids have any autonomy for a more personal take on routine textbook accounts of the Dandi March and Civil Disobedience?

You are right about this being a "pet theme". Also, dressing up, especially boys, as Gandhi, "impersonating" Bapu, so to speak. Bombarded as children are, by images of Gandhi everywhere in India—in schoolbooks, as statues on streets, on postage stamps, currency notes, billboards, wall posters—they do not paint with an innocent eye or a pure brush. Their Bapu, more often than not, looks like the Mahatma of grown-ups. Topics in competitions are usually proposed by adults. So, I would be cautious characterising these paintings as totally "autonomous". Yet, with an inscription here, an insertion there, award-winning entries in this important archive show originality, insight, imagination.

All this still begs the question: why were/are children so attracted to drawing Bapu? My hunch is, they respond to something "child-like" that in his own lifetime contemporaries noted about Gandhi. Hence, my larger theoretical interest as a historian exploring why the child mattered so much to Gandhian thought and practice, and to what extent the child-like subjectivity might have been critical to his ethics. These paintings are a starting point for such reflections.

Nikhil, Gandhiji in Dandi March, Standard X, Thakur Shyamnarayan High School, Kandivli, 2014. The top inscription reads: "First they ignore you, Then they laugh at you, Then they fight you, Then you WON!"

Please explain what you call "the aesthetic of the ambulatory"—Gandhi's "long strides hurrying to get to the end of British rule", as it were.

In a chapter titled "Artful Walking" in my book Gandhi in the Gallery, I develop the argument about this aesthetic of the ambulatory. Gandhi had a great penchant for walking. Besides being part of a daily regimen for physical and mental fitness, it was a way which resisted the quickening of life under industrial capitalism. Anti-speed, he was an early harbinger of what we today call "the slow movement".

Can children more naturally portray this energetic stance, instead of standard placid postures such as Gandhiji at his charkha?

Alongside sitting, spinning and meditating, a most common theme in art has Gandhi on his feet, danda in hand. Children see images of a striding Gandhi everywhere. Their drawing is likely to be influenced by it. In Mani Bhavan art competitions, the Salt March or Dandi Satyagraha is an oft repeated idea given to them.

Filoni, Barrister Gandhiji, Standard V, Nanavati School, Vile Parle, 2012

Another theme they keep returning to, possibly because it involved a child, is of Bapu walking on Juhu beach in late 1937/1938 with his young grandson Kanam. There is a photograph of the moment, which many professional adult artists turned to as well. It catches the eye of child artists, seeing someone their age having such fun with their dear Bapu.

What other episodes or figures from the Mahatma's life do youngsters single out to express?

This is a difficult question to answer without doing more research, especially interviewing the children. Pushed to a guess, I say that more so than grown-up artists, children are drawn to the figure of Kasturba, who appears in their paintings even when they are not asked to specifically draw her. She is quite ubiquitous in their artwork.

As Satyagraha is sometimes seen as not passive, but active resistance, do you feel the young are anyway inclined to interpret Gandhi's life in this vein?

Gandhi himself worried about the use of the term "passive" resistance, which in his time easily translated "satyagraha" (also in the beginning by Gandhi himself). He was no pacifist. In fact, the theory of non-violence is extremely complex, not about totally eschewing violence, as scholars have noted. It is worth recalling that Gandhi was concerned that young Indians were drawn to a more activist stance in the anti-colonial struggle and to figures such as Bhagat Singh, for instance. I'm not sure children find a natural attraction in Gandhian satyagraha. It is very much a learned ethic.

Have you found evidence of kids interpreting Partition?

In the Mani Bhavan collection, Partition per se is not a theme. On occasion, children focus on Gandhi's "martyrdom", one of the fallouts from Partition. That is the closest one comes to this. But they do turn, again and again, to the need for religious harmony, of the co-existence

of communities.

Is it possible to pick paintings you have been particularly struck by?

There are many wonderful works showing ingenuity. Shubham of Standard IX in GPP High School in Vile Parle, produced a painting called Gandhi in My Dreams. Gandhi is walking and talking with a bird, dressed like him in a dhoti, and carrying a stick. I puzzled over it. What incident in Gandhi's life is this painting pointing us to? The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi led me to a fascinating letter he wrote to the children of Sabarmati ashram from jail on May 12, 1930, giving a glimpse of the intimate, thoughtful relationship he sometimes established with a child:

"Birds are real birds when they fly without wings. With wings any creature can fly. If you, who have no wings, can fly, you will feel no fear. I have no wings and still I fly every day and come to you, for in my mind I am in your midst. There is Vimla, here are Hari, Manu and Dharmakumar. You also can fly with your minds and feel you are with me. A child who can think does not require much help from a teacher. A teacher may guide, but cannot give us thoughts. Thoughts arise in our minds... Write a letter to me, signed by all of you. Any child who cannot sign may draw a swastika."

Another set of my favourites depicts Gandhi painting, playing or riding a bike. An untitled work by Pavitra of Standard III, captures the essence of Gandhian-style disobedience. His cricket bat, marked Non-violence, strikes a ball called England—presumably kicking it out of the ground, out of the country, with the words: "You make rules, we break them."

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. Reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.mehermarfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!