The PDP-BJP coalition seems to be crumbling sooner than anticipated, with the passing of Chief Minister Mufti, the glue that held it together

Just how much difference an individual makes to a process is abundantly clear from the prolonged inability of the People’s Democratic Party and the Bharatiya Janata Party to form a government in Jammu & Kashmir following the death of Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed. It is apparent now, if it wasn’t earlier, that it was Mufti’s personality and political skills that had kept the unlikely coalition of the PDP and the BJP going. Now that he is no more, they are finding it difficult to connect.

Just how much difference an individual makes to a process is abundantly clear from the prolonged inability of the People’s Democratic Party and the Bharatiya Janata Party to form a government in Jammu & Kashmir following the death of Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed. It is apparent now, if it wasn’t earlier, that it was Mufti’s personality and political skills that had kept the unlikely coalition of the PDP and the BJP going. Now that he is no more, they are finding it difficult to connect.

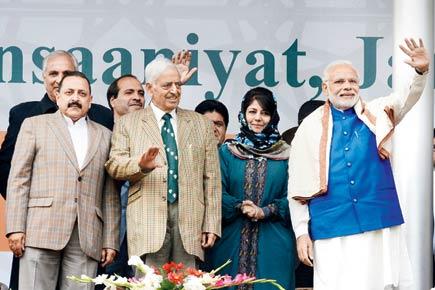

Late J&K CM Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, his daughter Mehbooba and PM Modi at a rally in November. The PDP went with BJP because of the efforts of Prime Minister Modi and Mufti. However, 10 months down the line, there is an estrangement and for this, New Delhi must accept the major part of the blame. Pic/AFP

On Tuesday, the Governor N N Vohra has called a meeting with both parties to ascertain their views. On paper they are still a coalition and there is no reason why the state needs to be under President’s rule. But behind the drama are longer range calculations of Mehbooba Mufti, the person who built the party with her grit and effort.

Most observers agree that Mehbooba would find it difficult to work with the BJP, but thought that the crisis would come a year or so down the line. But clearly they are wrong, and this also tells us a lot about her filial loyalty since now it becomes clear that she did not see eye to eye with her father on the alliance, but yet she stuck it out till it came to the stage when she had to take the decisions. Perhaps there is something more to the fact that Modi did not find it convenient to visit Mufti while he was in his death bed at the AIIMS in New Delhi.

There is a lot of talk as to the PDP’s unhappiness about the BJP not fulfilling on its promises under their common minimum programme. But PDP spokespersons have been somewhat vague in specifying what these are. In any case, the government is not even a year old and so the coalition partner can hardly be held to account. Word coming out of the PDP last week was that the party was unhappy on a range of issues, from relations with Pakistan to the revocation of AFSPA and development projects.

Actually, all the indicators are that Mehbooba may be readying to stake all in a fresh election, rather than depending on the vehicle of a coalition and, that too, with the BJP. This is evident from her reported remarks following her party meeting last week in which she has spoken of adhering to the “core ideology” of the PDP and going “back to the people”.

In great measure, the current emerging crisis is an outcome of the fractured verdict of the state Assembly election of 2014. In itself, the election was quite unique. For one, it was highly credible, with a 66 per cent turnout, with even some separatist-dominated constituencies seeing an enhanced vote. The PDP, which got 28 seats, was actually hoping to get at least 35 out of the total of 87 seats and make a coalition with the help of a junior partner, perhaps the independents or the Congress.

However, the BJP did spectacularly well and came second at 25, soaking up all the seats in the Hindu-dominated areas of Jammu. But it did have the effect of consolidating the Muslim vote, and the National Conference, which was expecting a washout, actually got 15 seats. The Congress got 12, and became the only party to have a presence in all three sub-regions of the state — Ladakh, the Valley and Jammu. In other words, the election also indicated the huge divide that had taken place with two of the bigger winners confined to specific geographic areas — the PDP in the Valley and the BJP in Jammu.

The PDP could hardly ally with the NC, with whom it competes for the Valley Muslim votes. And the Congress was neither inclined to have a coalition with the PDP nor did it have enough seats to make this a stable coalition. In the end, the PDP went with the BJP because of the efforts of Prime Minister Modi and the Mufti. In any case, the stable formula for parties in states like J&K and Tamil Nadu is to go with the party that runs the country.

However, 10 months down the line, there is an estrangement and for this, New Delhi must accept the major part of the blame. Modi has been so busy with his domestic development agenda and his numerous foreign visits that he has had no time to devote to Kashmir affairs. The result is that the issues close to the political heart of the coalition leader, the PDP, remained unaddressed. These were primarily the need for political dialogue between New Delhi and Srinagar of the type that Manmohan Singh had inaugurated. There is a facile assumption that since violence is down in the state, there is no need for any special gesture towards the state. In any case, the BJP has always opposed any special status for J&K. However, realpolitik demands that New Delhi be seen to be addressing the issues raised by separatists, even if it does not actually do anything about them.

The writer is a Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!