The Marathi play Mahanirvan turns 40 and it is time to revisit the cultural connections evoked by it. Based on the offbeat subject of funeral rites, it has found takers in seven Indian languages

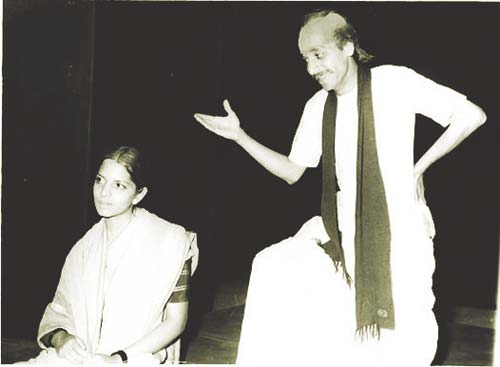

Actor Chandrakant Kale’s Facebook page flashed a happy post: “Mahanirvan turns 40. I was 23 when I essayed its central character Bhaurao. I am 63 now. As I look back, I remember the first houseful show in 1974 at Pune’s Bharat Natya Mandir, which instantly turned me into a popular singer-actor and strengthened my connection with experimental theatre.

Actor Chandrakant Kale’s Facebook page flashed a happy post: “Mahanirvan turns 40. I was 23 when I essayed its central character Bhaurao. I am 63 now. As I look back, I remember the first houseful show in 1974 at Pune’s Bharat Natya Mandir, which instantly turned me into a popular singer-actor and strengthened my connection with experimental theatre.

The play gave me a backbone and helped me to fight against my personal odds, my resource-poor background.” Social media users of all age brackets responded to Kale’s celebratory moment.

Some of the responses were reminiscences of watching Kale on stage, whereas some were laments about missing the glorious ‘70s in the history of Maharashtra’s performing arts.

The original Mahanirvan with actor (r) Chandrakant Kale

Kale’s reminiscences brought back another set of memories associated with Mahanirvan’s 25th anniversary in 1999, the year when it was revitalised with the original cast. Mumbai’s Yashwantrao Chavan auditorium hosted a felicitation of its playwright Satish Alekar who was then heading the Centre for Performing Arts, University of Pune.

Playwright Satish Alekar

The audience was treated to the Konkani avatar of the play presented by the Panaji-based Kalashuklendu group. This version, as against the original one had a shorter duration. But it did justice to Alekar’s ironical story of an insignificant Bhaurao whose post-death plea to be immolated in a closed-down crematorium leads his son Nana to bribe authorities.

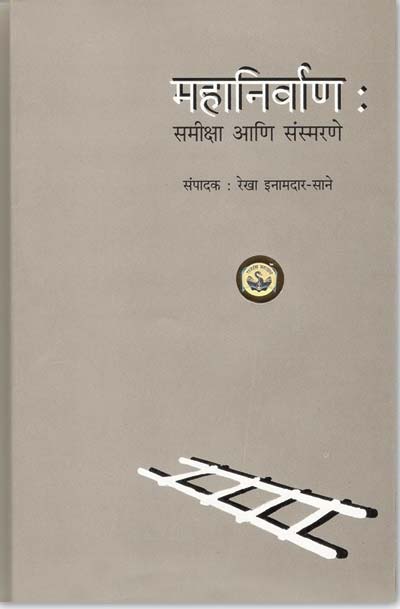

Mahanirvan’s world of cultural connections in a tome

Even with a basic understanding of Konkani, one could get the point Alekar was making about a ritual-ridden hypocritical Brahmin setting where the last wishes of a man are meant to be revered, whereas a young widow’s desires are destined to be unaddressed.

The book cover of Collected Works of Satish Alekar

The chawl set in the story was well-imbibed in the Konkani production, that curious gossip-mongering neighbourhood is a familiar feature in any Indian milieu. he play’s sutradhar is the dead Bhaurao’s soul.

The soul dictates his wishes and the mourners follow the orders. The keertan and gondhal art forms are used as musical devices to take the narrative forward. The original cast was blessed with singer-actor Kale who was made for the role envisioned by the playwright.

However, all productions of Mahanirvan did not necessarily have actors with similar talents. For instance, the Konkani version used the playback technique. The Panaji group adopted the Moche Madkari style of presentation in which all actors and singers are present on the stage throughout the play.

The actor playing the Konkani Bhaurao, therefore could fall back on the singers to depict the dead soul who refuses to depart unless cremated in a certain manner.

Tomb truth

The 1999 felicitation ceremony was an opportunity to listen to the maker of Mahanirvan who had penned the classic at the age of 24. It was a close encounter with a playwright who wrote his debut play when he had minimal stage experience as a college actor and a volunteer of Pune’s Progressive Dramatic Association.

The debutante’s (a post-graduate in bio-chemistry) anti-establishment take on the lower middle-class Brahmin Pune shook the intellectual discourse of the times. Even after the passage of 25 years, the appeal of Alekar’s Mahanirvan showed in the eclectic voices that evaluated the play in a closed auditorium space for an entire day.

The most memorable of those presentations was that of critic Rekha Inamdar Sane who was also the editor of commemorative volume in Marathi (Mahanirvan: Sameeksha Ani Samsmarane) encapsulating Mahanirvan’s journey. Very rarely are Indian plays archived, showcased and honoured in the way Mahanirvan has been in this volume.

From the first performance in which Alekar played Nana, each detail about the play’s production history has been captured. The English volume brought out by the Oxford University Press also showcases Mahanirvan’s English version. Noted theatre critic Samik Bandyopadhyay’s preface to the play makes a pertinent point: “The topsyturvydom of Alekar’s universe is a metaphor for the sheer anarchy of values and desires that marks the rise of the new Pune...”

Literature landmark

Mahanirvan’s trajectory has witnessed a convergence of rich talents. Its English translation was rendered by the iconic litterateur Gauri Deshpande whereas its Hindi avatar was shaped by lyricist-writer Vasant Dev. Dev’s translation was twice mounted by groups in New Delhi.

Famous TV actor Vinod Nagpal essayed Bhaurao in the Abhiyan version. Bhopal’s Rangmandal also produced the Hindi play, in which noted thespian B V Karanth played Bhaurao. Mahanirvan saw an apt reflection in Rajasthani, Punjabi, Gujarati and Bengali too.

Mahanirvan is a much-feted play. Despite its irreverent theme, it has lived in the collective consciousness of Indian theatregoers, of course the ones that subscribe to the experimental space. The play’s enduring appeal demonstrates the power and audacity of of Indian theatre to communicate a worldview that has limited takers.

Unlike any other art form, the intense focus of theatre is on human being and human nature has a legitimate space for introspection and examination. Mahanirvan speaks to that remedial space where people confront their real selves and question the rites and rituals they perfunctorily follow. What else can explain the long life of a play based on death!

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a Mumbai-based cultural chronicler

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!