Mumbai's annual obsession with the monsoon is nothing. In the 1800s, this was the epicentre of a pan-India gambling addiction hinged on the time and strength of the rains

THEY were simply spot-on. Predictions about the first rain this season pegged the expected date for June 1 — when sure enough the heavens broke. In the context of such conjecture, the same pre-monsoon newspaper ad front-paged for 30 years kept the public waiting and watching: the countdown to MRF Rain Day showed the tyre company’s muscled mascot Hercules-like hoisting high a dark cloud.

THEY were simply spot-on. Predictions about the first rain this season pegged the expected date for June 1 — when sure enough the heavens broke. In the context of such conjecture, the same pre-monsoon newspaper ad front-paged for 30 years kept the public waiting and watching: the countdown to MRF Rain Day showed the tyre company’s muscled mascot Hercules-like hoisting high a dark cloud.

ADVERTISEMENT

Based on tales narrated by his father Manilal Shah, Chira Bazaar resident Dilip Shah, 75, pins 1886 as the beginning of barsaat ka satta. Pic/Shadab Khan

A hundred years before that very visible campaign, 1880s Bombay was already powered by its own elaborately organised monsoon gambling system dubbed barsaat ka satta. Surprisingly far from innocent, the city was

no stranger to burglary, fraud, opium smuggling and local addictions, this satta among the most popular.

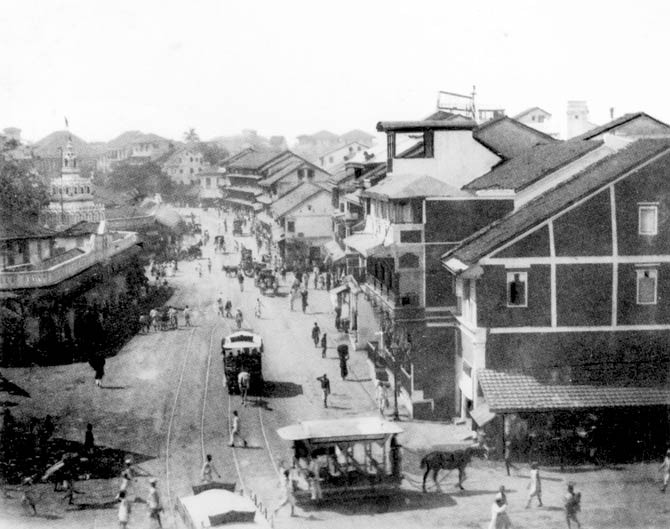

Mumbadevi Street, photographed by Raja Deen Dayal in the late 1880s, derived its name from the temple of the goddess Mumbadevi

Mumbadevi Street, photographed by Raja Deen Dayal in the late 1880s, derived its name from the temple of the goddess Mumbadevi

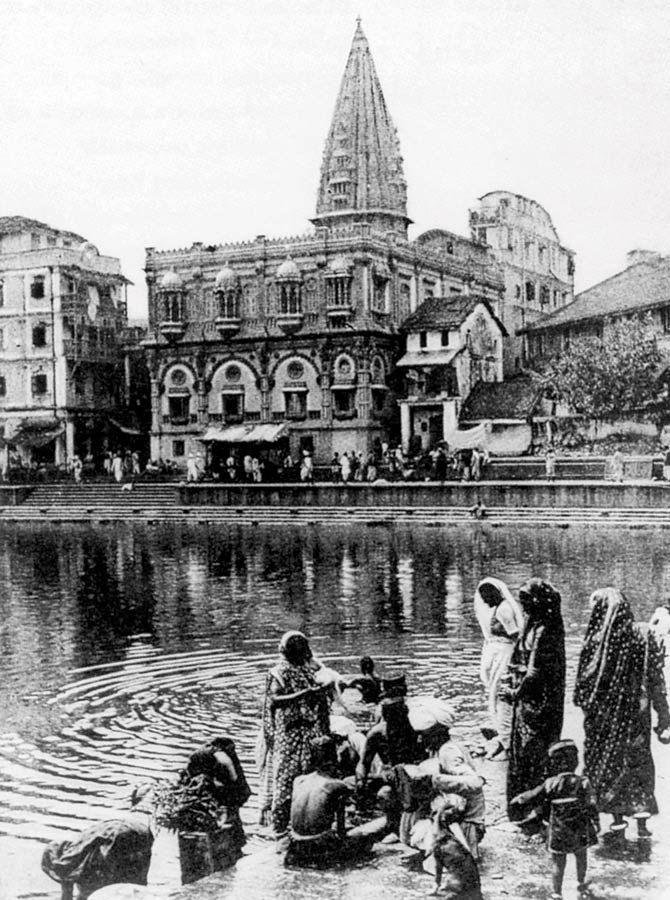

An account in A Biographical Sketch of Sardar Mir Abdul Ali, chronicling the life of that distinguished Head of Detective Police, mentions the hub of operations “in the heart of the native town near Mumbadevi Tank”. Desperation drove gamblers to take risks with impunity under the gaze of the Koli fishing community’s patron goddess Mumba Devi, worshipped at Mumbadevi Temple on a bank of the tank in Kalbadevi.

Which was relocated here in the 18th century from its original site near Bori Bunder. Pic Courtesy/ Bombay the Cities Within; Eminence Designs Pvt. Ltd

Which was relocated here in the 18th century from its original site near Bori Bunder. Pic Courtesy/ Bombay the Cities Within; Eminence Designs Pvt. Ltd

According to Acharya and Shingne’s 1889 work, Mumbaicha Vruttant, business boomed from a special house behind Mumbadevi Tank till 130 stalls sprang up to cope with thronging customers. A clerk in each registered bets made by a partner in trade with people coming in. Books were actually available too, as at horse races.

For four full monsoon months the hooked spent hours atop roofs, studying patterns of gathered clouds to figure when exactly they could burst. Speculation peaked with the shift and drift of Nimbus forms. When these clouds hung low, betting became bolder. A man perhaps declared, “It’s 3 o’clock, it will rain before half-past three,” another added, “Rain should drop between half-past three and 4 o’clock” and so on. The game included picturesquely precise details, like whether thunder and lightning would accompany a downpour. Besides gauging how clouds hover, gale guessing relied on the knowledge of the natural world — winds, tides, moon phases, and typical behaviour of insects, birds and animals just before rain.

Fine collective intelligence created unique instruments to test and record the observations of these human weather vanes. Accurate appliances indicated the volume of rain, with the experts quite particular as to what constituted a fall. The Calcutta ‘mori’ form of satta used the device of a sand-filled box in the open. Water cascading within a prescribed time, in excess of a marked limit, seeped out from a tiny tap. It had to in a steady stream, no matter how slowly or briefly. This proving a difficult decision, an appointed referee gave his final verdict. The privilege was assigned to the proprietor of the shed housing a stall; the lessee had no voice.

The “lakdi” satta assumed larger proportions with an entire portion of a terrace blocked off. On four posts with a firm foundation rested a masonry structure with a flat, smooth surface. Near one end was a cup-shaped hollow in the stone, from where a tube led over the edge of the “table”. Water on the stone wound a path into the cup, and from the tube to the ground. This avoided arguments, otherwise the few drops of a passing drizzle were disputed. The basic rule was that water must run from the tube; merely dropped it meant nothing to note.

The satta saga described by one who has the story from close quarters is unbeatable. The wettest evening finds me sipping some cutting masala chai only a Gujarati kitchen brews best. I’m all ears as 75-year-old Chira Bazaar resident Dilip Shah and his hospitable wife Renuka share tales told by his father Manilal. Retired from an almost century-old shop on adjacent Princess Street (Laxmi Medical, once Madras Leather Works), Dilipbhai pins 1886 as the beginning of barsaat ka satta. Peering down from a window seat of his flat in the sole tower that dwarfs the crowded, squat-homed lane pelted by rain, he says, “Though those first forecasters had worse weather, thanks to the British drainage system, our narrowest gullies didn’t flood. Water collecting up to 150 inches never overflowed.”

What did overflow was the money lining the satta players’ pockets. Bets ranged from a rupee to a thousand, stakes soaring as the habit flourished. An estimated 20,000 rupees changed hands on a single day of heavy showers. Gambling stall owners pocketed tidy commissions despite hefty fines imposed by CP Cooper, Chief Presidency Magistrate.

Old residents smile, recalling the madness, excitement and consternation whipped up by this activity. Overcast skies spelt non-stop natter. Drivers leaned out of Stearns and Kittredge-built trams clanging their noisy way along Kalbadevi and Girgaum, to exchange tips on signs sniffed of a cyclonic storm. Men trooped in from mofussil corners of the country “to gamble with the clouds” as they cockily announced to fellow travellers en route.

It was hardly idle layabouts alone who were ensnared. The capital market controlled by the influential Shroffs (their hundis were a kind of draft honoured across India), these men virtually functioned as private banks. They were distinct from moneylender Sarafs who dealt with clients on a smaller scale. Both Shroffs and Sarafs slacked off under the satta spell.

“Bombay was the hotbed of speculators and gamblers and the harm they did to the city was simply incalculable,” states the stern text of the Mir Abdul Ali book. “Servants gave up their callings, merchants deserted their trade to pursue this vice, the cause of ruin of many a family... The place had the appearance of an annual fair, a tamasha. This gambling was not conducted fairly, the consequence frequently a fight and serious assault on one or other of the parties concerned.”

No wonder vexed Raj officials grew more distressed by the day at the wild goings-on. The malaise they countered was intoxicating for its boisterous players, always long strides ahead. After raiding gamblers’ dens in Chembur “village”, it was hoped the Act of 1887 would curb this social menace. Denying, defying, the addicts argued their indulgence was on account of business being less brisk from July to Diwali. Sir Raymond West, judicial member in Lord Reay’s government, pronounced gloomily, “The ingenuity of a certain class of gamblers found means of evading the law.”

Even in those times, overworked and underpaid constables, called “tukdiwalas” for accepting bribes, bore the brunt of patrolling Bombay’s diverse and burgeoning population. (Interestingly, the Thagi and Dakaiti division of the Indian police, which laid the foundation for the Criminal Investigation Department, preceded Scotland Yard.)

Showers still lash their lane as I leave the Shahs. Dilipbhai points out the neighbouring church is the earliest in this area — Our Lady of Good Health, Cavel has stood for 150 years (the Portuguese converted several Kolis of Cavel in north-east Dhobi Talao to Christianity). Casting her eyes further over the panoramic sweep seen from their living room, Renukaben offers a lively vignette about Mumbadevi tank in the distance. Before it got filled, the waters revealed hidden loot possibly flung in by clever fleeing thieves — the dagina (jewel) market of Zaveri Bazaar located right behind. It is said there were coins, gold, little lockets… And, dare we think, soggy bits of a betting book or two?

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at mehermarfatia@gmail.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!