Recently, social media was abuzz with images of the Hindu goddess, Kali, projected on New York’s Empire State Building

Recently, social media was abuzz with images of the Hindu goddess, Kali, projected on New York’s Empire State Building. As I looked at the image, I could not help conclude that the artist was not Indian. My friends asked why. I said, ‘High cheek bones!’

Recently, social media was abuzz with images of the Hindu goddess, Kali, projected on New York’s Empire State Building. As I looked at the image, I could not help conclude that the artist was not Indian. My friends asked why. I said, ‘High cheek bones!’

ADVERTISEMENT

In India, Kali is seen as one of many forms of the Goddess, one that represents nature at its most elemental.

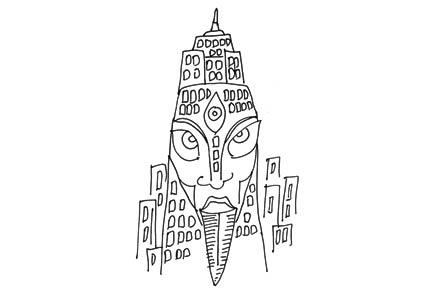

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

So, she is visualised with a garland of human skulls; her blood-smeared tongue stretched out. She is even described as naked and dancing at crematoriums, thus embodying death and life, violence and sex. In images, her eyes are made to look kind, her body soft and rounded and her nakedness strategically covered with long hair, garland of human skulls and a skirt of human limbs to make her ‘bhadra’ (decent).

Traditionally, Kali was distinguished from another goddess, Chamunda. The former was characterised by her outstretched tongue, while the latter by her gaunt body and ‘high cheek bones’ — much like the starving models we find on European catwalks. Kali was the earth who drank blood to quench her thirst; Chamunda represented barrenness, starvation, and death. Kali travelled on a lion; Chamunda travelled on ghouls. Kali was associated with black cats; Chamunda with scorpions.

But Kali, as mentioned in Western literature, is very different. The West could not believe that anyone would consider a female form as divine. The nearest they came to it in the last 2,000 years was the virginal Mother Mary. So, initially, they saw Kali as the Devil who drinks blood. In 19th century Orientalist fiction, she became the goddess of thugs and murderers who demanded blood sacrifice. Indian freedom fighters saw Kali as the form of Mother India stripped of her glory!

In the 20th century, feminists found her to be a symbol of liberation. She was the opposite of Lakshmi who sat demurely massaging Vishnu’s feet. She danced on her husband, Shiva. This idea fascinated Western feminists, who took to the image literally. They saw her nakedness as defiance and subversion. They saw her copulating with Shiva by sitting on top of him as assertion of female sexuality. In New Age Religions, Saraswati, Lakshmi and Kali were equated with the three forms of the Goddess: spring, summer and winter, or virgin, matriarch and crone. Kali and Chamunda images merged to be gaunt with high cheek bones and outstretched tongue, naked, sexual, and surrounded by blood and gore. This form also appealed to Heavy Metal bands.

Over the years, Kali’s popularity has grown in the West. This version is unrecognisable for many Hindus. Many even find it insulting. But those who get outraged need to remember that images often travel across cultures and acquire new meaning. What Kali means to a feminist in America will be different from what she means to a feminist in India, and very different from what Kali means to a devotee, or a tantrik. The image on Empire State Building was supposed to remind us of nature’s wrath as human progress causes the extinction of many human species. Divine anger in Hindu mythology is ‘leela’, a mock show put up by a mother trying to get her petulant children to behave. But this affectionate view of Kali is something that many European and American artists and academicians and new-age tantriks will argue is just typical Indian denial and domestication of the ‘true feminist and liberated Kali’. The not-so-easily-outraged Hindus will simply roll their eyes and chuckle.

The author writes and lectures on relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at devdutt@devdutt.com. The views expressed in these columns are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!