The essence of every religion and the basis of every moral science sermon is good deeds. But of course, not even those who call themselves spiritual abide by it.

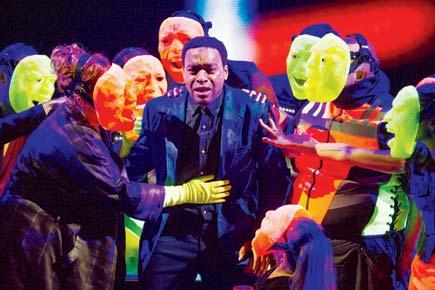

A scene from the play Everyman

The essence of every religion and the basis of every moral science sermon is good deeds. But of course, not even those who call themselves spiritual abide by it. In this age when the lines between good and evil are being blurred all the time, how can a 15th century morality play be turned into a contemporary piece of theatre?

The essence of every religion and the basis of every moral science sermon is good deeds. But of course, not even those who call themselves spiritual abide by it. In this age when the lines between good and evil are being blurred all the time, how can a 15th century morality play be turned into a contemporary piece of theatre?

ADVERTISEMENT

Rufus Norris, the newly appointed head of London’s National Theatre answers this question with a production that uses words, visual effects, music, dance and every old and new technique that can be used in a modern play and comes up with Everyman. UK’s poet laureate Carol Anne Duffy has worked with the old text to create a new play (in free verse) that works in tandem with the surreal imagery.

A scene from the play Everyman

In the 21st century version of the play, God (Kate Duchêne) is a woman — to be precise, a weary cleaning woman — who starts with the words:

Good day at work?

You find me at my work —

She who cleans the room before the party,

Mops up afterwards…a vicious circle...

Skivvying for those who are immortal.

Or so they think. I see you have your drink?

Prosecco? Seize the moment while it lasts! While it lasts.

All done. Ship-shape and Bristol fashion;

Ready for the dancing, boozing, passion —

Oh yes, I’ll be sweeping condoms up

Before this night is done — and worse. Don’t ask.

I’m nothing if not thorough, caring, dutiful.

And you…are all so beautiful.

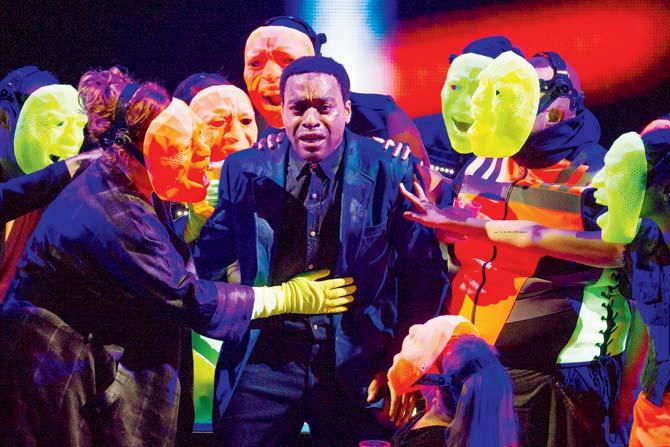

The brilliant casting has Oscar-nominated (for 12 Years A Slave) actor Chiwitel Ejiofor playing a man celebrating his 40th birthday with a big blowout bash — booze, drugs, much lewdness and an almost aggressive need to ‘enjoy’. Many a young professional around the world will identify with this picture of a hedonistic lifestyle.

Ejiofor as Everyman, in a well-cut suit, is a swaggering picture of health, flaunting the power, vanity and arrogance that comes with money. Like so many of our rich men (and women), he thinks he can buy anything — he certainly can buy sex and friendship — and that he is indestructible. A rap song goes:

24/7 gotta make a livin’, on my second wife — I, upgradin on the Wi-Fi,

revvin’ up the, revvin’ up the, revvin’ up the lifestyle,

Rich as Croesus, thank you Jesus, connected to the thigh-bone

is the f****n’ iPhone,

Happy f****n’ birthday, woof woof, beware of the dog,

Masters of the Universe you’re —

listen to me, listen to me — you’re God.

What’s God like God like God like God like-

you’re God like — hear the truth.

But God calls him a “lazy, worthless, thoughtless, thankless fool” and sends Death to fetch him. Everyman stands for all humans who have contributed to destroying Earth, “cavorting with Wrath, Greed, Sloth, with Pride, Lust, Envy and with Gluttony.”

Then, Death (Dermot Crowley) arrives, wearing overalls and green surgical gloves and carrying an ordinary shopping bag instead of a scythe. A shocked Everyman is not prepared to die. Death is certain his time is up and he has to meet God for his day of reckoning. He tries to enlist the help of his friends, to give a good account of his life, but they quickly abandon him. (“But we can’t just leave a birthday party/ and go to the Afterlife! It’s too random.”)

He goes to meet his family — old parents and embittered sister — whom he has been neglecting for years (“Everytime we phone, you’re in a meeting”). Now when he wants their support, they don’t want to help. (Sister: “Let me get this clear — you want the family to stand before God with you? Are you for real?”)

What does he have to show for his life then, except worldly goods. Maybe God will be impressed by his riches. But all the possessions that he has worked to amass also turn him down. (“In front of God dot com, you’d stand with zilch.”)

When he has thrown his money and flung about his credit cards, a smelly, raggedy drunk, Knowledge (Penny Layden) teaches him the humility he needs to meet his maker. He is ashamed to learn that he hasn’t even got enough good deeds to get God to favour him. Walking on broken glass and hurting his feet to suffer has no effect. Finally, he understands that he needs to pray, and he can’t even remember the prayers he learnt at school.

In the end, it’s about materialistic people who have destroyed Earth and will have to pay for their greed with mass destruction — a deadly tsunami sequence. Before Everyman accepts the finality of his death, he encounters the senses — knowledge, beauty, sensuality, passion, discretion, conscience, strength — and understands that he has to go face God alone. (Shailendra had written a beautiful song expressing this elementary philosophy in his song for Teesri Kasam: Sajan re jhoot math bolo, khuda ke paas jaana hai/ na haathi hai na ghoda hai, wahan paidal hi jaana hai.)

Today, with a loosening of moral bonds, the play does not have the fire-and-brimstone effect that it might have had in the conservative past, but it still has the power to make people pause and take stock of their lives.

And, how can an update of a play be without the ultimate symbol of vanity — the selfie? Even Death takes one!

More than anything else, this production underlines the value of collaborations — a Hollywood star, a celeb poet and a reputed director. Add imagination and meaning for a production that’s worth its dazzle. When will we manage something like this on our stage?

Deepa Gahlot is an award-winning film and theatre critic and an arts administrator. She tweets at @deepagahlot

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!