There was no call, none whatsoever, irrespective of the provocation, for a BJP MP to hold forth on Nathuram Vinayak Godse, the man who killed Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

There was no call, none whatsoever, irrespective of the provocation, for a BJP MP to hold forth on Nathuram Vinayak Godse, the man who killed Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Given our inability, as a nation and as a people, to view events of the past in a dispassionate manner, and our politicians’ penchant to exploit this to their advantage, it’s best for an MP to avoid comment that generates needless bluff in Parliament and bluster in television studios.

There was no call, none whatsoever, irrespective of the provocation, for a BJP MP to hold forth on Nathuram Vinayak Godse, the man who killed Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Given our inability, as a nation and as a people, to view events of the past in a dispassionate manner, and our politicians’ penchant to exploit this to their advantage, it’s best for an MP to avoid comment that generates needless bluff in Parliament and bluster in television studios.

ADVERTISEMENT

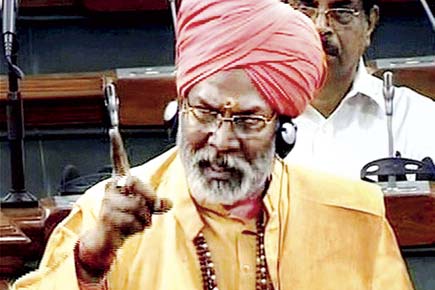

BJP’s Sakshi Maharaj first described Godse as a ‘nationalist’, and then backtracked. Pic/PTI

Hence it was frightfully stupid of Sakshi Maharaj to first describe Godse as a “nationalist,” and then backtrack. “If I said something by mistake I take it back,” he said by way of a qualified apology to his outraged critics, “I don’t consider Nathuram Godse a patriot.” The retraction is based on the premise that his fellow parliamentarians felt offended; everybody loves to be seen as a hero worshipper of Gandhi although most would not think twice before violating the most fundamental of Gandhian precepts.

The verbal slanging match and display of indecorum we witnessed in Parliament over Sakshi Maharaj’s comment, which he has now withdrawn, should not, however, deter us from asking the question which would no doubt pop up in the mind of those uninitiated to the fine print of the history of India’s partition in 1947. That question is: Why did Godse kill Gandhi? This is by no means to suggest, even if remotely, a justification for an unconscionable deed.

But no story, journalists are taught, is complete without four ‘Ws’ being answered: What happened? Where did it happen? When did it happen? Why did it happen? About Gandhi’s assassination, we know what happened, where did it happen and when it happened. Those who have gone beyond these three questions also know why it happened, or at least, why Godse and his co-conspirators believed (we don’t have to share that belief or get hysterical over it) they were right in doing what they did and went to the gallows. But most are ignorant of the fourth ‘W’: Why?

Politics is a violent affair in this part of the world. But Gandhi’s assassination was different. Not only were his killers Hindu, they killed a man who had by then come to be regarded at home and abroad as an “apostle of peace” and symbolised the unique doctrine of ‘non-violence’. In those early days of freedom, it was unthinkable that anybody would dare raise a finger, leave alone a gun, at Gandhi. Yet Godse did the unthinkable, with more than a little help from Narayan Apte, Vishnu Karkare, Gopal Godse, Madanlal Pahwa and Digambar Badge. The historic trial that followed (it was held in Delhi’s Red Fort) captured the imagination of the nation.

The first book of any substance on Gandhi’s assassination was Stanley Wolpert’s Nine Hours to Rama, published in 1962 and promptly banned by the Government of India; the ban still remains in place. The other book that generated tremendous interest was Manohar Malgonkar’s The Men Who Killed Gandhi, a gripping recreation of India’s partition, independence and Gandhi’s assassination on January 31, 1948. It was first published during Mrs Indira Gandhi’s Emergency when manuscripts were cleared by censors who merrily ran their blue pencil through text which probably they could not even comprehend. “This made it incumbent upon me to omit certain vital facts,” Malgonkar wrote in the introduction to a new edition of the book, “such as, for instance, Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar’s secret assurance to Mr LB Bhopatkar, that his client, Mr VD Savarkar, had been implicated as a murder suspect on the flimsiest ground.”

Malgonkar writes about those terrible days with restrained eloquence. Hindu and Sikh refugees from Pakistan were struggling to keep body and soul together. Many of them had lost their loved ones in the partition riots: women were raped in front of their husbands and children; young girls were abducted; men were disembowelled; trains arrived laden with dead bodies; people fleeing marauders were set upon with ferocious brutality. Madanlal Pahwa, a young refugee, Malgonkar writes, “reached a place called Fazilka, in Indian territory, and discovered that another refugee column in which his father and other relatives had set out, had fared much worse. They had been attacked by Muslim mobs: ‘Only 40 or 50 had survived out of 400 or 500...”

Delhi was flooded by nearly one million refugees, all of them desperately looking for food and shelter. They were distraught and traumatised, unable to figure out why their lives had been turned upside down in so gruesome a manner. Nor could they understand the rationale behind protecting Delhi’s Muslims. What left them aghast was Gandhi’s insistence that Hindu and Sikh refugees should be sent back to Pakistan and Muslims who had left India be brought back. It didn’t make sense.

The proverbial last straw for Gandhi’s assassins was his threat to go on a fast to force the Government of India to accept Pakistan’s demand to which Jawaharlal Nehru was opposed.

Nehru famously declared that giving the money to Pakistan would mean providing it with “sinews of war”. In the end, Gandhi had his way. But did Gandhi’s perceived disregard for the sentiments of millions of refugees (half-a-million people perished in the violence, 12 million were rendered homeless) justify Godse’s action? What inspired Narayan Apte, son of a well-known historian and Sanskrit scholar, to decide on January 13 (the day Gandhi declared he would go on a fast to press Pakistan’s demand for R55 crore) that he must turn into a killer? What was Madanlal Pahwa’s role in the conspiracy? And why did Badge turn approver? Malgonkar’s classic answers these and other questions; it’s history brought alive. Read it.

The writer is a senior journalist based in the National Capital Region. His Twitter handle is @KanchanGupta

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!