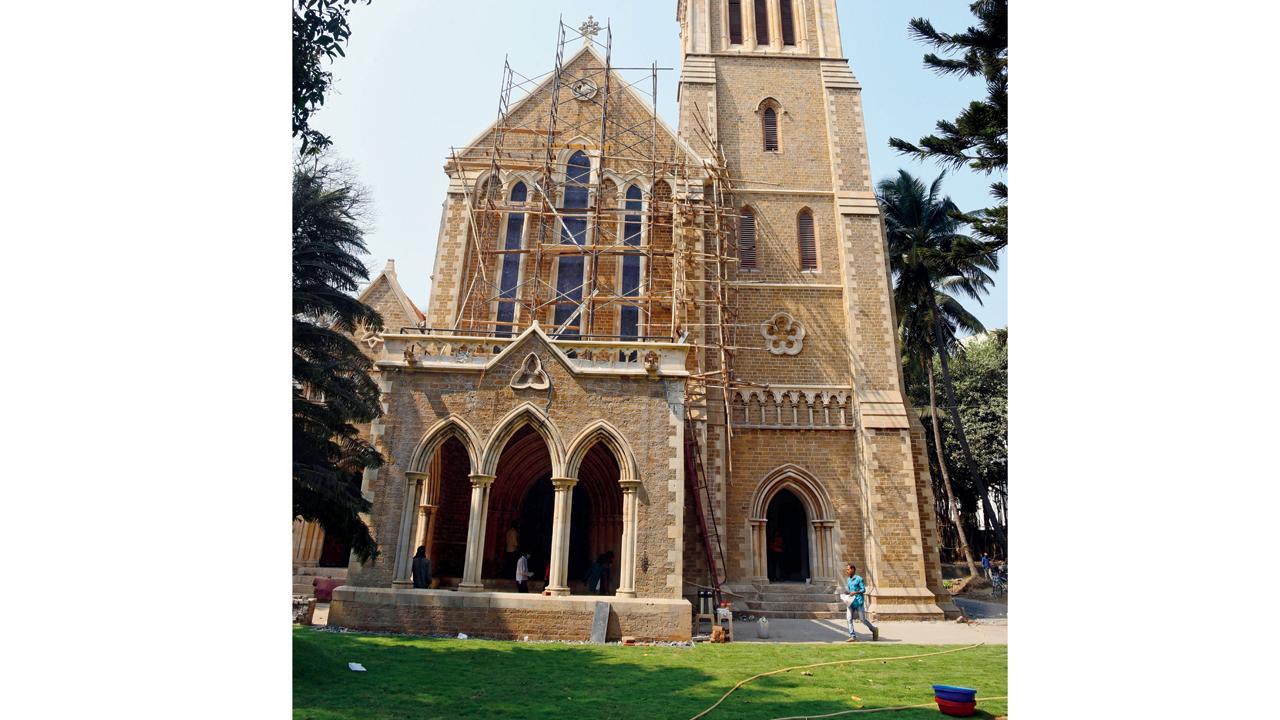

On the southern-most tip of the city stands a church that’s rare for its historical significance and architectural marvels. The Afghan War Memorial Church restoration, stuttering over 25 years, comes to a happy end after two years of continuous toil

The stained glass windows feature the Apostles of the New Testament and needed to be treated along with the frames they were set in. For the broken clerestory windows at the sides of the church, locally-available glass replacements were created. Fresh timber trusses were crafted for the roof

When Kirtida Unwalla stepped into the precincts of the Afghan War Memorial Church at what’s possibly one of the farthest ends of Mumbai, the enormity of the restoration and conservation challenge required for the 165-year old structure struck her like a sock in the face. She remembers it in utter disrepair; like “remnants of a war-zone”. This was 1998.

ADVERTISEMENT

Last week, Unwalla stood inside the Grade-I heritage structure, with the seven teams of consultants who had worked on it for the past two years, and called the result “a dream come true”. “When we started,” she remembered, “I had just got back from the UK after my architectural conservation training. It was 1996.” This was her first professional conservation project. Unwalla’s association with the church erected as a war memorial for the 4,500 British soldiers and 12,000 camp followers who perished in the first (1838 to 1940) and second (1878 to 1880) Anglo-Afghan wars, is 30-year-long. A project of this size requires funds, and the first lot came from the Church Committee, INTACH Mumbai, and “friends of the Afghan Church”, she recalls.

The 198-feet spire of the church was one of the toughest challenges; the restoration involved undoing the damage caused by previous work. Pics/Shadab Khan

During the first four phases between 1998 and 2009, the restoration of the stained glass windows and altar roof was taken up on priority. Long-time friend and associate, glass conservator Swati Chandgadkar, whom Unwalla calls a “partner for life”, worked on the primary stained glass windows and the clerestory windows, which flank the sides of the structure. The windows had all been commissioned for manufacture at glass studios in England. Which meant that the 700 cracked pressed-glass panes had to be restored with a locally-made reproduction; this was done by embossing and deep etching.

Funding fell through after. With the church’s parishioner strength down to 20-odd families, there simply wasn’t enough to hold up a project of this scale. Amita Baig, executive director of the World Monuments Fund India (WMFI) asked Unwalla to prepare a report on the original extent of damage to the historic structure. In 2022, the World Monuments Fund India (WMFI) in collaboration with Citi India, furnished the Rs 14 crore required to complete what had been started.

From the breathtakingly beautiful windows, our gaze travels upwards towards the wood-panelled teak roof, which the Afghan Church Pastorate Committee member Christopher Elisha cannot tear his gaze away from. “I’m seeing the original colour of these panels for the first time,” the third-generation parish member says with a smile. Leakage had eaten away at the bituminous layer inlaid in the teak wood panels, causing the wood to rot from within. Now, fresh timber trusses arch out from the stone pilasters.

The 198-feet spire of the church, which was built in 1865, required attention. The damage from previous repairs had to be stripped away. “Previous restoration efforts included adding a cement onlay with a thick mesh of three-inch steel. Cement and stone just don’t go together,” Unwalla declares. This church has eight bells, a rarity. Their mechanism had to be figured out so that they could ring in tandem, like they do now. Elisha, in fact, is the one responsible for playing hymns and carols on the bells, just as his father and grandfather had done before him. “While the Afghan Church was built as a place of worship, it was also a navigational landmark for ships approaching the harbour as the steeple could be seen from miles away,” says Sangita Jindal, Chairperson of JSW Foundation and Board Member, WMFI. “It has stood out as an important navigational and historical landmark due to its grand spire and eight bells.”

Around the altar, salts from the earth had risen up, damaging the Porbunder limestone pillars and walls. A clay poultice was applied, and the salt drawn out, over a period of two months. Outside, to prevent water from sloshing against the side of the walls during the heavy monsoon, looped iron chains extended from a pole ensure that the water is channelled away from the façade, entering a soak pit from which it can harmlessly evaporate and drain away.

Seven to eight teams of consultants were involved in the extensive conservation and restoration work, which spanned two years

Apart from the structural restoration, the artefacts housed within the church also required a facelift. “The task given to us was of conservation, to ensure the longevity of these elements. After that, we focused on restoration, to enhance the message that these objects meant to convey,” says Anupam Sah, art conservator, who with his team, supervised the restoration of the pulpit, marble and metal plaques, screens, letterings, mosaics, memorial cross and the baptism font at the entrance, along with the standards hung to commemorate the regiments of the Bombay Native Infantry.

For Unwalla, more than a church, this structure is a tribute to human life and the work of a lifetime. “We cannot forget what the church was built for. It’s a garrison church; it was built for the soldiers who fell in the Afghan War. It’s a monument church, envisaged by the East India Company as tribute to the heroes, the soldiers.”

But adding the regiment names of Indian soldiers who perished has been missing all these years. That’s why an information centre is being built inside, to publish its history and allow it to serve as a means of education. “With the Gothic architecture of Mumbai now on the World Heritage List, perhaps one day, this [church] too will find its place there,” Baig hopes.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!