After veteran clock repairer Bandu Jadhav, a former AC mechanic takes on the job of keeping CST's clocks ticking

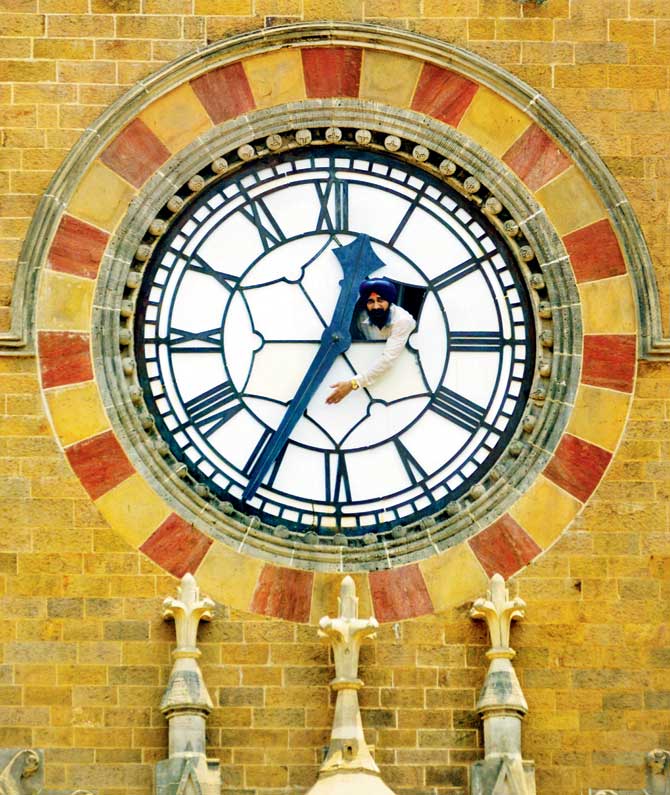

Mahinder Singh leans out to clean the frames of the 129-year-old CST clock tower. Pics/Bipin Kokate

ADVERTISEMENT

Observing Mahinder Singh at work, it's hard to tell he has been at this job for only a month. After veteran clock mechanic Bandu Jadhav retired last month, the task of ensuring that the clock atop Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus ticks on time, now rests with Singh, 45.

Two flights of stairs beyond the second floor of CST's main building — one of them a spiral one, the other a decrepit wooden ladder of sorts — lead to the 129-year-old mechanical clock. The journey might seem cumbersome, but for Singh, it's all in a day's work.

Mahinder Singh leans out to clean the frames of the 129-year-old CST clock tower

The clock runs with the support of a 350-kilogram weight, and needs to be wound every four days. We catch Singh during duty hours on Thursday noon, when he is busy winding it. He makes his way through what appears to be an intimidating network of iron and bronze wheels, with hooks, pins, locks and weights, interconnected with rods, engraved with markings. Singh needs to turn one of the wheels 15 times to fully wind the giant clock. Once wound, the clock can function for four days, before it needs another charge. "I follow a schedule — every Tuesday and Friday noon," Singh tells us, as he leans out of the frame to clean the minute hand from the outside.

The 45-year-old left his job as an air-conditioner repairer and joined the Railways in 2002. He has been a part of the telecom maintenance department since. "After Jadhav sir's retirement, the post of the clock mechanic was surrendered. Now, the repair and maintenance of all clocks fall under the purview of telecom maintenance department. That includes the mechanical clocks, the GPS masterclock, the platform clocks and the indicators," says Singh, who winds 16 clocks every day within the CST premises, which includes the mechanical clocks in the chambers of all heads of department.

Singh isn't qualified in horology. "Before I joined the Railways, I knew nothing about mechanical clocks. Whatever I know about mechanical clocks, I learnt by watching Jadhav Sir — how to wind, how often to wind, oiling, maintenance, restructuring, reading time, everything."

Singh commutes from Badlapur daily, reporting to work at 9 am and spending his day around timepieces. As we chat, his eyes fall on one of the iron rods in the grid. "That's the minute hand," he tells us, "It's running two minutes slow." As we marvel at how at one glance, he identifies a slant of no more than a degree, which translates into two minutes in clock-speak, he toggles with a few levers and fixes the glitch.

Ask him how it feels to be the man who's now showing Mumbai the time, and he says, "Whether it's the giant clock on the outside or other smaller clocks inside, they are my responsibility, and it is my duty to maintain them." Then quickly adds, "I don't think I am doing anything great, it's my job. But yes, a job like this helps you realise the value of time like no other."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!