Make in India Week is the springtime of public art in the city, but is it all good, ponder Mumbai artists

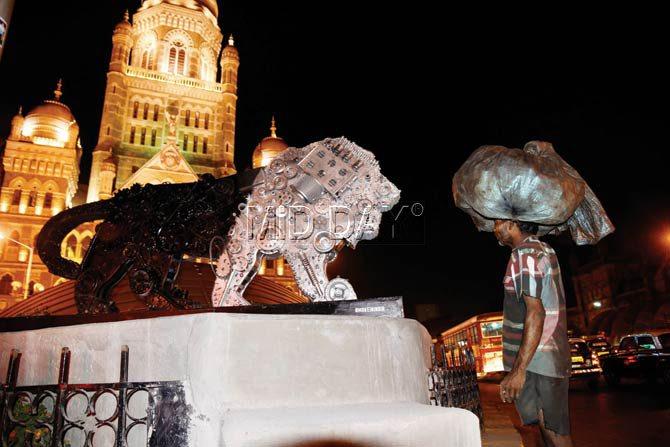

That Make in India is not just investment in the manufacturing sector, but also about art and culture, is the theory behind 16 lions, 21 nandadeeps and a set of other public art installations that have come up in the last one week across the city. Part of the investment extravaganza that is Make in India Week, these installations are visual reminders of PM Narendra Modi’s favourite catchphrase, but have also drawn attention to the state of urban public art. For instance, Make in India's mascot - the lion with gears aplenty - is found on various traffic islands across the city and is made of auto spare parts, fibreglass and metal.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Make in India lion at CST which uses the design of gears. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

The event is a coming together of the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP), ad agency Weiden + Kennedy, New Delhi, as well as a host of other creative agencies and individuals. While the installation designs were conceptualised by Weiden + Kennedy and Red Diffusion, the execution is by film and television art director Nitin Desai. Furthermore, Desai, who has been commissioned by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), has also designed the sets for the Maharastra Pavilion at BKC, the stage for Maharastra Night at Girgaum Chowpatty, as well as the grand dinner with the PM at the Turf Club.

Desai, who attended a school in Mulund and has been art director for Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam and Dostana, has brought in the best of Mahrashtra’s cultural spirit into the events. The nandadeep, for instance, is the symbol on the state seal. “The Maharastra pavilion at BKC has a trimurti that we see at Elephanta. It has been great to see the government and creative agencies work together,” said Desai.

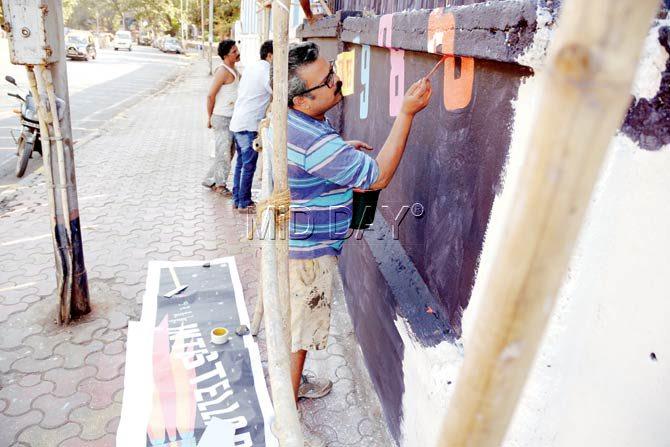

Street artist Ranjit Dahiya readies a wall at Worli Seaface for Make in India. Pic/Atul Kamble

Among those who were approached for the art installations was sculptor Arzan Khambatta, whose works are found in traffic islands at Worli and Kala Ghoda. Khambatta turned down the offer on learning that he would have to replicate the logo design provided to him. “That kind of work can be done by fabricators or 3D printed,” he stated.

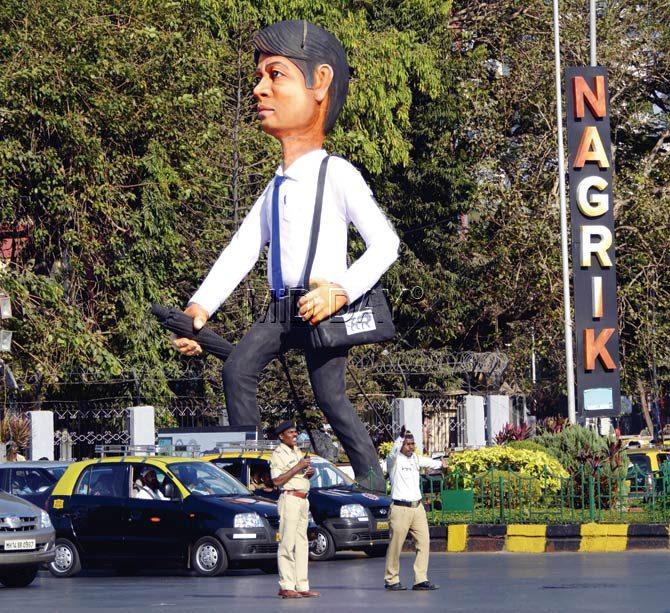

Armed with a bag and umbrella, the working Mumbaikar ‘Nagrik’ at Haji Ali is an installation for Make in India Week. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Ranjit Dahiya, street artist and muralist, who founded the Bollywood Art Project, has also been commissioned by the Central government to pay homage to Make in India week at three centres across the city – Worli, CST and Marine Drive. Painting a space research themed mural at Worli on Friday, Dahiya said, “It is great that street art has received recognition from the government and support from the BMC. We should beautify this grey city more.”

Whether the installations will be temporary or find a permanent home is yet to be decided by the BMC. While Additional Municpal Commissioner (city) Pallavi Darade refused to comment on the matter, an official from BMC looking into the installations said the civic authorities are yet to make up their mind.

However, not all in the art fraternity are pleased with the quick-fix public art that has invaded our streets. A South Mumbai gallerist requesting anonymity, said, “It is a monumental task for artists in the city to get permissions from the BMC to carry out any public art installation. And then, when the opportunity arises during Make in India Week to carry out public art, it is swept away unfairly.”

Ranjit Hoskote, poet and cultural theorist who has co-curated the ongoing State of Architecture exhibition, on seeing the 25-feet tall Nagrik – a working white-collared man with a bag and umbrella – at Haji Ali, said, "Let us be clear. This is not art, and this is not an installation.” Hoskote suggests that the need of the hour is for street furniture and well-paved streets. “What passes of as public art is just decorative nonsense. Moreover, artists cannot be pressured to make public art. It has to be an organic process."

On similar lines, gallerist Arshiya Lokhandwala said, “[Public art] cannot be a sudden burst of things and a quick fix. There is a lot of money going into this [Make in India] that can be spent on the inculcation of young artists. It has to be better structured.”

Khambatta continued, “While it wouldn’t be fair on the installations to comment on their quality, it is a healthy exercise to have public art installations. At this point, it shouldn’t be about good art or bad art.” Curator Farah Siddiqui is hopeful that this is a good precedent set by the BMC. “Many of the top officials are well-travelled and knowledgeable about public infrastructure. Let's hope this leads to better things."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!