What does it take for a riot-ridden village in Maharashtra to turn into an advertisement for communal harmony? A 100-year bond of peace

Assistant Sub-Inspector Shivaji Bangar remembers accepting his posting to Burundi in Ratnagiri in 2012 with dread.

ADVERTISEMENT

An iftar last Wednesday (second day of Ramzan) saw both Hindus and Muslims sit across the table for the traditional breaking of the fast. Pics/Satej Shinde

"When I was posted here and given the charge of the beat, I was scared. I'd heard that it was an area prone to communal riots," says the 44-year-old. Sitting in his chowky, a 100-sq-feet space on the Dapoli-Burundi Road, he says the local police would have to station five vehicles outside the village every time there was a religious festival that would see a procession — Ganesh chaturthi, Gokulasthami, Holi, Ramzan, Eid and even the annual festival of Sufi saint Mohamood Shahwali Peer Dargah.

The last two years have, however, been a dream. The village of 6,500, which has a 60 per cent population of Hindus and 40 per cent Muslims, has seen no escalation in violence. In fact, last January, the two communities signed a 100-year peace pact headed by community leaders on a R100 notarised stamp paper. "For the last two years, I have been handling all festivals with only two home guards and two constables for help. And everything has gone off smoothly," says Bangar.

Violence on the seashore

If you arrive at Burundi, 10 km from Dapoli on the Dapoli Highway, it might be difficult to imagine its troubled past. Your average view would be that of men gathering fishing nets and women busy drying the day's catch. Narrow lanes lined with old houses, lead you to the Arabian Sea where kids enjoy a bout of cricket on the beach. The village, 250 km from Mumbai, subsists on fishing sending its catch to the district, Goa and Mumbai.

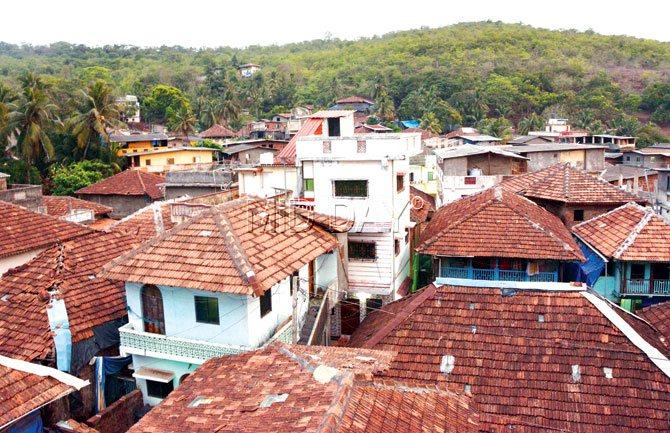

The village which lies on the Ratnagiri coast has a population of 6.500

The village which lies on the Ratnagiri coast has a population of 6.500

Its first recorded communal riot occurred in 1986. Elders of the village recall that a marriage procession was passing through the village. Loud music and the accompanying dance disturbed those praying at the local Jama Masjid. A few of them expressed their opposition to the procession and a fight ensued.

The situation remained so tense for the next few days that a curfew was imposed. A case was registered against some of the residents under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) (unlawful assembly). For months, a team of the State Reserve Police Force, along with the Home Guard, was stationed in the village to maintain law and order.

Rules have been laid down stating the care that members of both communities must take while celebrating festivals

Another incident that they recall is in 2012 when, during Gokulashtami, a procession — youngsters dancing with loud music — encircled the masjid three times. The two parties had an argument over it. Villagers assaulted each other. Though the cops brought it under control, the village remained tense for days.

Survival instinct

The need for peace also comes from a deep-rooted survival instinct. Ashraf Adam Mastan, a 46-year-old villager who is one among the 10-member committee that signed the bond, says, "Fishing is our only means of livelihood. Fighting for years was a waste. Our livelihood is dependant on fishing. Moving out will leave us without a home and source of income. Therefore, ensuring peace was our only option."

Assistant Sub-Inspector Shivaji Bangar at Wednesday's iftar

The need is especially strong when out at sea. Even when there were fights on land, at sea, the two communities would forget their differences and be ready to help each other in case of trouble.

The 2012 riots woke the villagers up to the need for a long-term solution for peace. Five members each from both communities along with the police, formed the Samanvaiy Samiti in 2013, with help from Bhagwan Patil, Former Deputy Superintendent of Police of Khed Division. "The committee held meetings once a month mandatorily. More meetings would be held if a festival was approaching to decide the appropriate manner of conduct for everyone. Small issues or petty fights would also be resolved," adds Bangar.

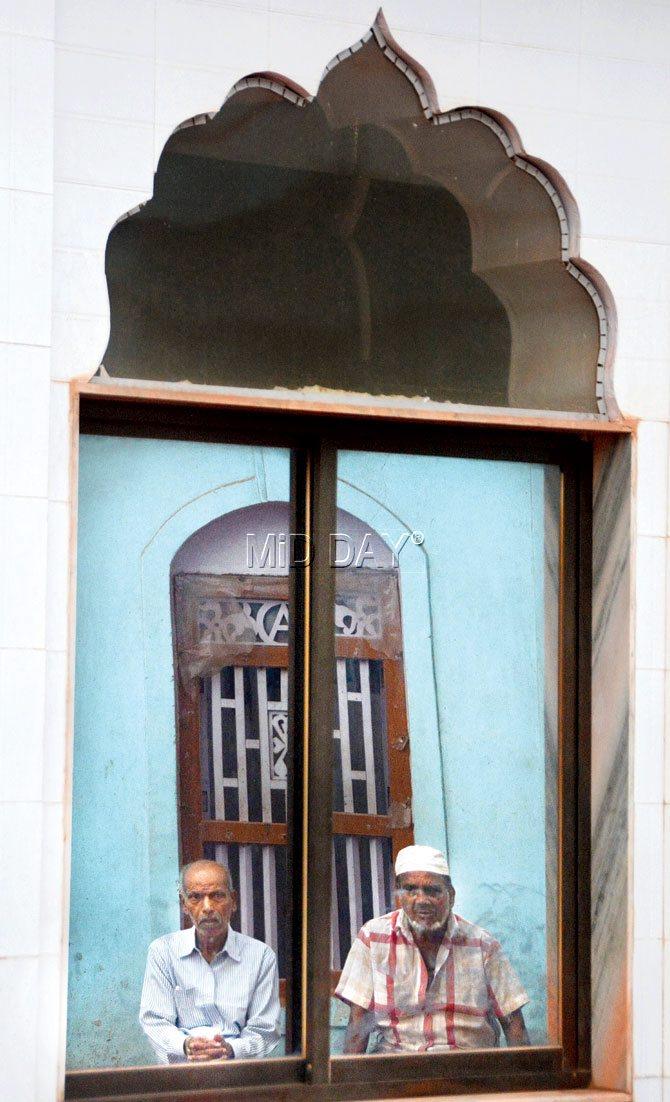

Members of the peace committee, Kasim Alimiya Shirgoankar and Azad Alimiya Diwekar

Fifty meetings were held between the two communities and the policemen to find a solution and draft the 100-year bond. While sorting issues between themselves was working well enough, the villagers wanted to keep the tradition of unity alive. So, they thought of putting it down on paper," says Bangar. The records and documents are a plan for the next generation, which may have otherwise ignored the Samiti.

100 years f peace

On January 17, 2015, the bond was prepared on a s stamp paper which was later notarised. The 10 members became the core team to ensure that it was implemented. Dr Sanjay Shinde, Former Superintendent of Police, Ratnagiri, who was recently posted as Deputy Commissioner of Police, Kalyan Division, was present during the signing.

The bond states that processions during any festival — Ganesh puja, Holi, weddings, Gokulashtami, Satyanarayan puja — should avoid timings that clash with the namaz, especially if it involves a band playing loud music.

Additionally, the processions should avoid the mosque premises so that those praying are not disturbed. Similarly, a processions such as that of the Urs of Mahamood Shahwali Peer Dargah, should lower music volume when passing by the temple and avoid hurting sentiments of the Hindu community. "Now, when a procession has to pass by the mosque, two people from the Hindu community come to us and ask us to share prayer timings. They conduct their processions peacefully. We are invited for the procession and are hosted by our brothers," he adds.

If someone passes away from the committees, another one from the community is nominated from among the elders in the village. The elder should be known to have good relations with everyone including those from other villages. Those who break peace face ostracisation.

Nitin Ganpat Sate, 40, a villager and also the president of the local Hindu Panchakrushi Samiti, says, "We are thankful to the police for supporting this initiative. Instead of increasing cases by registering every petty fight, the cops have played a vital role in uniting the two communities and supporting the cause of peace." He adds that now the two communities are so close, everyone is invited for the others' festival.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!