Can architecture help heal cultural trauma? This year’s winner of the Charles Correa Gold Medal looks at how mindful design intervention can save the Lalbaug precinct’s unique spatial character

An integral part of Lalbaug’s spatial character is its gullies; (right) the precinct is surrounded by daunting redeveloped, luxury high-rises that are visible reminders of the trauma of urban violence. Pics courtesy/Prachi Kadam

As a history buff, Prachi Kadam, who graduated from LS Raheja School of Architecture earlier this year, made a study trip to Germany in her second year. While reading up about the Holocaust survivors’ stories, she was introduced to the term cultural trauma. “It wasn’t just the Jewish community that was affected, but also their architecture as synagogues and houses were burned down. I noticed that there was a transposition of the trauma from the people to their architecture, which damaged their culture,” shares the Thane resident. She noted that one way in which the Jewish community healed was by rebuilding the ruins of the past: “It stayed with me. I started thinking about the terms architecture, culture and trauma.”

ADVERTISEMENT

So, for her final-year thesis, the 23-year-old student proposed that cultural trauma is not just the wounding of people, but of places and spaces, too. She questioned if an application of trauma studies in architecture can help heal cultural trauma. And last month, her thesis, titled Decoding Cultural Trauma: Case of Girangaon, Mumbai, ensured she walked away with the prestigious Charles Correa Gold Medal. “This is the first time the competition was opened to all students across India, so it’s even more special. It was a complete surprise,” Kadam gushes.

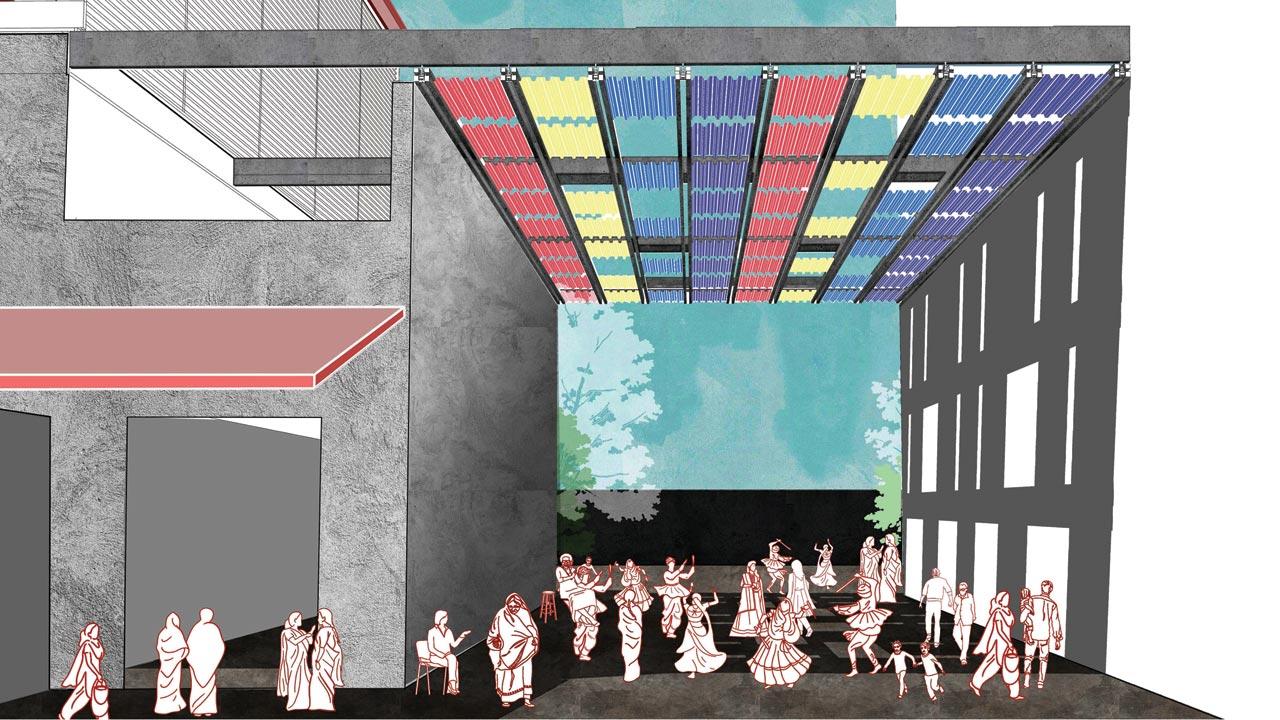

A sketch of the pavilion of impermanence. Kadam proposes that the flexible design allows the space to change as per different festivals

A sketch of the pavilion of impermanence. Kadam proposes that the flexible design allows the space to change as per different festivals

A threat to Lalbaug

After surveying case studies across India, Kadam settled on Girangaon, an erstwhile mill neighbourhood. The mill owners’ strike of 1982 led to a cultural wounding of the place, with the mills shutting down. It changed the identity of the mill abode from its rich girni (Marathi for mills) culture to a consumerist one, thereby gentrifying the area, she reveals. To understand the area, Kadam documented the spatial character of her selected site: Lalbaug. The precinct comprises two main gullies — chivda gully and masala gully, apart from a fish market, which is the driving force behind the Lalbaugcha Raja, established in the 1930s, she reveals. “Around this time, the mills, too, started coming up. Digvijay Mills is next to the precinct. The gullies and the mill workers’ chawls came up around the market and the Lalbaugcha Raja.”

However, after the mill owners’ strike, the land started getting commercialised. Now, almost 60 per cent of the 600-acre Girangaon area has undergone redevelopment, with the bustling and culturally diverse Lalbaug precinct next in line. “Right now, Lalbaug market is affordable, fulfilling the domestic needs of many. If the cultural trauma of redevelopment were to strike Lalbaug precinct, then the market will lose its character,” Kadam notes. The true nature of Lalbaug’s market, which lies in these gullies and their chaos, will vanish, she cautions; it will erode an 85-year-old culture as redevelopment doesn’t account for it.

Prachi Kadam

Prachi Kadam

Mindful design

To devise an intervention strategy, Kadam documented not only the “dukaans and makaans of Lalbaug”, but also the way people sit and move, what kind of furniture they own, how they travel and the way the festival transforms the space. Instead of strapping changes, she conceptualised a plan revolving around “designing for informality” — simple solutions to uplift the lives of residents. “I retrieved the two main gullies, and the fish market, as they’re integral to the place. I introduced service roads to tackle the overlap of vehicular and pedestrian traffic. To break the monotony and provide ease of access, I added intermediate streets between the chivda and masala gullies,” she illustrates.

Among a slew of other design tweaks, she proposed shifting part of the housing site near chivda gully, adding spaces to encourage community exercises like achaar-making, small parking spaces in front of shops, and 400-mm platforms along the gullies to store masalas and hold temporary infrastructure during the festival, instead of drilling the road every year. “You don’t always need to build huge structures to make a change. Small, thoughtful design interventions can have an impact as architecture is about creating for people,” she signs off.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!