Trace the story of Girangaon, the city's cluster of cotton textile mills and how they've been gentrified, in an interactive, multimedia exhibition

This week, if you walk into Columbia Global Centers' Mumbai space, you'll spot videos on iPads and TV screens that showcase artistes performing the Marathi folk dance Naman and singing Shahiri Powadas. These vie for your attention with a website, VR headsets and 360-degree videos, with soundtrack et al, which urge you to explore a cluster of erstwhile mill lands of central Mumbai known as Girangaon, not be confused with Girgaon.

ADVERTISEMENT

The exhibition documents the history and culture of Mumbai's mill lands and their gentrification over the last seven years. Pic courtesy/Swapnil Bhole, Pukar

Past forward

Titled Archiving Mill Lands: The Mythologies of Mumbai, the interactive exhibition has been designed by Delhi-based HELM studios. It is based on a seven-year-long documentation project by the research collective PUKAR, supported by Dr Ravina Aggarwal, anthropologist and programme officer at Ford. The idea: to archive Girangaon for posterity before it disappears from the city's fabric.

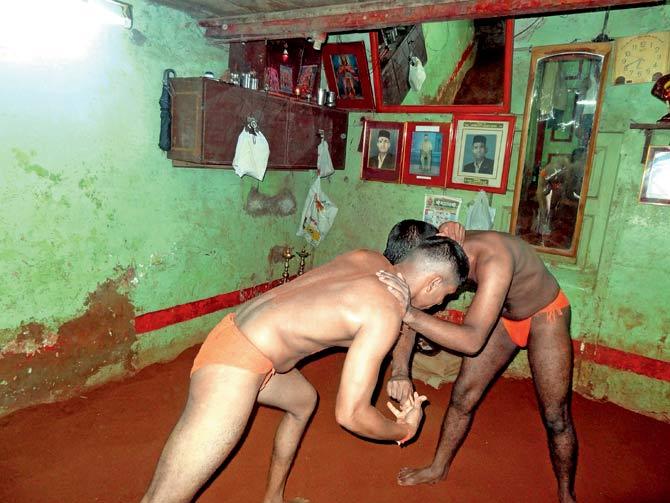

A gala in Chinchpokli used as an akhada

"When all the 54 cotton mills located in Girangaon were churning out beautiful textiles [in the 19th century], generations of mill workers contributed to the city's economic, social, and cultural prosperity. They mainly lived in chawls, built around a central courtyard. It served as an open space for sports, family celebrations and community festivals, building a unique, shared lifestyle and community-specific identity within the residents. With the onslaught of gentrification, this started getting transformed, and hence, the need to archive," says Dr Anita Patil-Deshmukh, principal investigator at PUKAR.

Jayashree Varape runs a khanawal in Byculla

She led the team - Ajit Abhimeshi, Triveni Mane, Kiran Sawant, Shrutika Shitole and Tejal Shitole - to document Tardeo, Byculla, Mazagaon, Reay Road, Lalbaug, Parel, Naigaon, Sewri, Worli and Prabhadevi using right-to-research methodology, based on the principle of experiential learning, since the team members are residents of these neighbourhoods.

They conducted interviews with mill workers, their children and grandchildren, local artistes, women running khanawals (lunch home or a stall), small-scale entrepreneurs, activists, politicians and union leaders, and produced 250 video interviews, five case studies, and close to 20,000 images, which will comprise six photo-exhibits at the venue. They even roped in 120 local artistes to engage in the documentary production of eight folk art forms, including Lezim, Lavani, Powada, Bhajan, Dashavatar, Naman, Bharud and Balya. "All of them narrate stories of the workers' lifestyles, and their social and political upheavals."

The team also framed age-old institutions like galas or single rooms in chawls that would house anywhere between 20 and 100 people, mostly single men. "They worked in three shifts in the mills, so, at a time, only six to eight people would sleep in the room," says Deshmukh. In a video interview, former mill worker Balasaheb Mohite shares, "If one of those 'Galekars' was to get married, everyone would collect currency notes and make a garland out of them. Their feeling was that of immense happiness that one from them was actually entering marital bliss and that he did not follow the wrong path in life."

The future

Deshmukh says that despite the SC verdict of distributing 200 of 600 acres of mill lands to mill workers for low-cost housing, the implementation has left them with less than 88 acres. "A majority of mill workers have either returned to their villages, or work in jobs like security. Their children have low-paying jobs in malls that have replaced the mills. Some prefer to continue living here, but the fancy towers are unaffordable. Many have been dispossessed of their area and have had to move further away from the city."

Till: November 25, 10 am to 6.30 pm

At: Maker Chambers VI, Jamnalal Bajaj Road, Nariman Point.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!