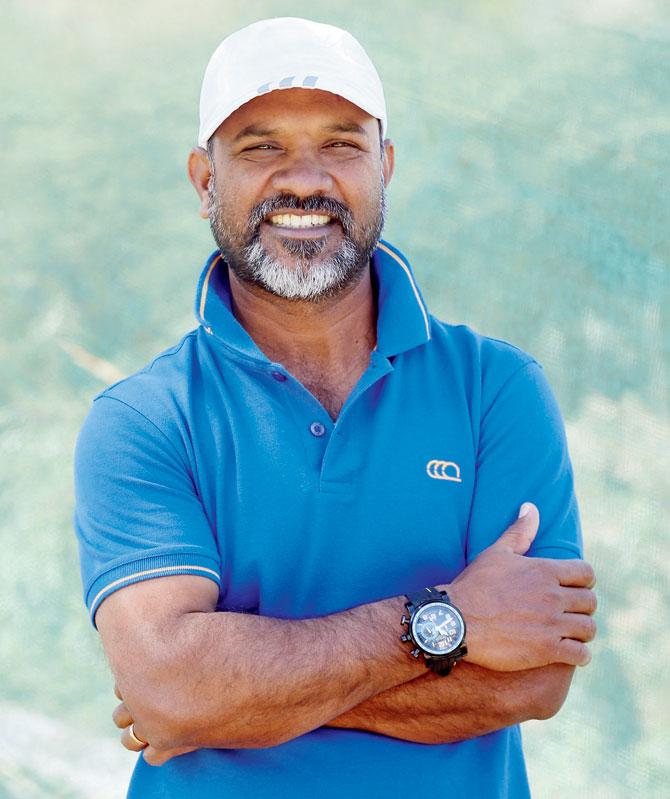

With no experience in working with the visually impaired or with cricketers, taking the Indian blind cricket team to top slot in two T20 World Cups was a mind game for this political science professor

Patrick Rajkumar

Two months ago, Patrick Rajkumar, 43, sat in his room at KR Puram, Bengaluru, with thoughts running through his mind like a freight train. About to begin the task of preparing the Indian team for the T20 World Cup Cricket for the Blind, the pressure on him to keep the title won in 2014 was immense. Failure was not an option.

Interestingly, Rajkumar, who has been coaching the country's Blind Cricket Team is neither a career coach nor a career sportsman.

A professor of political science at the city's Government College, he was in 2012 approached by the Cricket Association of the Blind in India (CABI) to build the team. At the time, Rajkumar had last played a sport during his graduation years at St Joseph's College, an alma mater he shares with Rahul Dravid. Yet, even then his main sports were table tennis and football. Cricket came a far third. But, cricket coaching was not his brief. "It was to build the team. I was hired more for my man management skills than cricketing abilities. I was never meant to be the conventional coach," says the man who then went on coach the team for a number of tournaments — and the latest tournament was won last week at Bengaluru's M Chinnaswamy Stadium, defeating India's perennial arch rival, Pakistan, by nine wickets.

Blind cricket played by the partially-sighted and blind cricketers is being managed by the World Blind Cricket Council (WBCC) since 1996. Until date, four One-Day International World Cups have been held. The T20 version of the game was introduced for blind players in 2012.

This time round, his strategy, he knew, might permanently place him in the bad cop bracket — but it would be a strategy that worked. He told the players to shift focus from individual honours to match situations. The team comprises those with blurred vision, the partially blind and totally blind. Rajkumar can speak eight languages, making communication with the players, who come from different regions in the country, easy.

He never asked the association why they picked him, but his biggest challenge was getting the players to trust he was fit for the job. "Initially, many players felt that I will not fit into their world. But after winning the first World Cup, they realised that this man can be trusted," he says, adding, "I don't invent players. What I am trying to do is convert players into champions. Appearing in a match alone does not guarantee a win. For that, you need the right attitude. So, I implement a regimental training system from 50 days prior to the tournament."

The day would begin at 5.30 am and players were expected to hit the training ground immediately. "I believe that it's important for players to have an undisturbed environment once they hit the ground. In the beginning, it was tough for them; six to seven hours of training through the day," he says.

Once the players adapted, Rajkumar divided his daily training sessions prudently. "The mornings were devoted to fitness and cricket skills development — batting bowling, fielding. In the evenings, we focused on personality development wherein we addressed factors like how to handle crowd, tackle pressure situations, how to talk to the media, etc."

Discussing how the players eventually got around to putting the team first, he talks of the semi-final against Sri Lanka in which batsman Deepak Singh, one of the team's star players, was dropped. Like any other player, Deepak too was hurt. He did not vent in public but took the decision in his stride. "Later, after we won the match, he came up to me and said: 'Sir, your strategy was right and I am so happy that the team has won.' I reckon that was the effect of buddy system," Rajkumar says.

The team winning its second title, Rajkumar hopes, serves as inspiration for visually challenged persons across the country. "From a cricketing perspective, this victory assumes significance because this tournament was held in India.

Unlike in 2012 and 2014, where there was no real publicity for the tournament, the number of people who knew about this event was significantly higher this time. I believe this win can change the lives of several blind persons."

But, as much as he wants recognition from the rest of the country, he wishes that sports' most powerful governing body, the Board of Cricket Council in India (BCCI), would open its eyes to the visually impaired players. "I hope we get the board-patronage soon so that blind cricket can spread its wings. Also, players and coaches like me can work in a stronger environment."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!