Priya Pathiyan talks to Sarabjit Kaur, who recently attended a seminar by Hervé This, the father of molecular gastronomy, in Paris, and learnt how to replace her regular cooking ingredients with molecular compounds

Food

It was a dream come true for Sarabjit Kaur, who is pursuing her degree in Food Innovation and Product Design at the AgroParisTech-INRA in Paris, France, to work with Hervé This, the man behind the original concept of molecular gastronomy — the science of cooking — that he founded more than 20 years ago, along with his late associate Prof Nicholas Kurti. Today, the world’s top chefs, including Heston Blumenthal and Pierre Gagnaire, turn to Hervé for inspiration.

ADVERTISEMENT

To add a feather in her cap, she recently attended the International Centre for Molecular Gastronomy (ICMG) workshop from June 3-5 in Paris. Here, the 25-year-old rubbed shoulders with the foremost scientists and chefs in the world of molecular gastronomy. At the meet, Sarabjit met physical chemists from across the world — Argentina, Chile, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Korea, Lebanon, Portugal, Serbia, Switzerland and the USA.

But, it has been a long journey for Kaur, who was a student of Kendriya Vidyalaya and has pursued BTech in Bioprocess Engineering from SRM University, Kattankulathur, Chennai. “My father was in the Indian Air Force and I spent most of my childhood travelling around India with my family. After his death in June 2006, my mother, who is a homemaker, and

my brother supported my education,” she says.

Strawberry soup spoons

Kaur met her idols through this programme. “I got to be a student under Hervé This, which is a great honour. I also got to meet world-renowned three-star Michelin chef Pierre Gagnaire and to spend an evening in his kitchen on Rue Balzac in Paris,” she exults. Presently, she’s busy working on her Masters thesis to develop an enhanced protein smoothie based on the current consumer demand in Ireland.

Experts take part in a group discussion at the seminar

The science of food

Hervé, director of the workshop committee, says, “The objective was to bring together a group of scientists to collectively discuss the science behind the practices carried out in the kitchen. Previous workshops were held on the role of emulsions, the effects of cooking methods on food quality and the management of food flavours. This time around, in the seventh IWMG, we discussed the thermal treatment of plant tissues.”

Participants attend a practical workshop on molecular gastronomy

A subject, which at first listen, might sound like something you may hear in the ladies’ compartment of the Virar local — the topic of ‘cooking vegetables’. Jests apart, he explains, “The emphasis was on gastronomy (the science of cooking) rather than nutrition, as well as on domestic and restaurant cooking rather than the industry.”

“I spent two years of my Masters course in understanding food and how it is made, what ingredient makes something taste better than the other. While listening to scientists and chefs during this workshop, the importance of molecular gastronomy in cooking was reiterated.

Sarabjit Kaur

It is important for people involved in the preparation of food to have a basic knowledge of the science behind cooking. It should be made part of the curriculum of any such course, along with learning cooking techniques,” says Kaur.

Note By Note Cooking

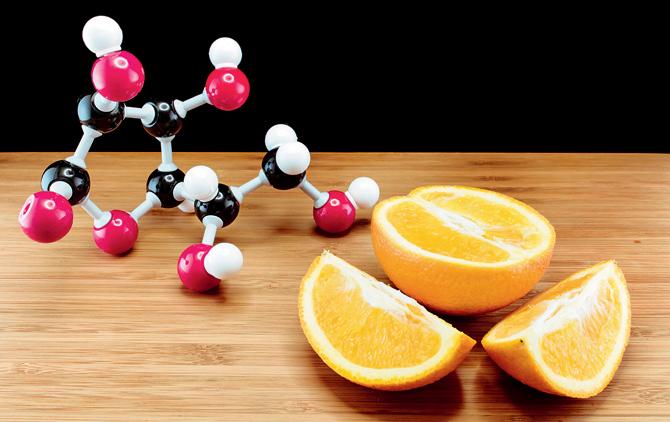

The main focus of the seminar was Note By Note (NBN) Cooking, a new idea of cooking that hasn’t yet reached Indian shores but is firing the imagination of the scientific as well as the culinary world. According to Hervé, “The initial proposal was to improve food... but the next idea is obvious. It is to make dishes entirely from compounds. NBN cuisine is not using meat, fish, vegetable or fruits, but rather compounds, either pure compounds or mixtures.” When we ask whether it’s restaurant-ready, he says, “Yes, it is. Everybody is very excited by NBN, and some participants have decided to sell the ingredients.”

Herve This

“The dishes presented at the finals of the third international NBN cooking competition in Paris were absolutely amazing. NBN cooking gives a lot of independence and space for creativity to the chefs. Also, buying compounds such as proteins, starch, flavours and colours is much cheaper than buying conventional ingredients. NBN still needs to be refined to create food that resembles what we eat. But it is a solution to preventing food waste on a large scale. It has a long way to go and I am proud to be a part of it,” says Sarabjit. She’s certainly in the right place at the right time.

While the first such workshop was conducted by Prof Nicholas Kurti and Hervé This 23 years ago in Sicily, this one discussed the progress molecular gastronomy has made today in various parts of the world.

The experts demarcated the differences between molecular gastronomy (a scientific activity), molecular cooking and molecular cuisine (the way of cooking using modern tools) and NBN cooking. “The workshop was very exciting and a bit intense as we spent the whole day just discussing molecular gastronomy and NBN cooking,” says Sarabjit, who had conceptualised a recipe for an adaptation of Asian chicken soup with noodles and fried egg using starch, protein, water, colourants such as beta carotene for egg yolk and flavour compounds for mint and chicken flavour. She, however, didn’t present it in the NBN cooking contest as she felt she needed more time to fine tune the concept. “Next year, perhaps,”

she says.

The other sessions

Other sessions led by Prof Roisin Burke of the Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin, Ireland, as well as Dr Christophe Lavelle of Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France, talked about different aspects of Molecular Gastronomy and Education. Many top chefs would have gladly traded in their toques to be a fly on the wall at the session that discussed the connection between Culinary Art and Molecular Gastronomy.

According to Sarabjit, highly technical questions flew fast and furious throughout the three-day seminar… What are the exchanges between plant tissues and their environment during cooking? Are there other important molecular modifications? How are minerals exchanged? What is the effect of cooking on saccharides and amino acids? What is the extent of Maillard reaction (the process of browning, which results in a different colour and flavour) during the cooking of vegetables? Prof Jose Miguel Aguilera from the University of Santiago, Chile, chaired the detailed discussion on how an ingredient’s consistency gets modified during various processes, including steaming. Naturally, colours and the changes occurring during cooking were also delved into deeply.

When we ask Hervé which, according to him was the most exciting session he says, “The open questions threw up a lot of surprises. From simple ones, such as ‘Is there a difference between cooking potatoes in cold water (at the start) or in hot water?’, or ‘Do male eggplants have more nicotine than female?’, or ‘How much of the sugars remain in carrots after cooking?’ to more complex ones such as ‘Is there hexose dehydration (forming HMF) and sucrose hydrolysis inside vegetables during cooking?”

The workshop aims to collaborate with experts globally and come out with a free open journal. “The aim is to make it easier to share ideas and come up with more creative solutions to common questions,” he signs off.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!