A new exhibition at London's Victoria and Albert Museum celebrates Kipling Sr, who had, arguably, a far greater India connect than The Jungle Book author

The Great Exhibition India by Joseph Nash, 1851. It is said that the exhibition at Crystal Palace, south London, fired Lockwood’s imagination in art and all things Indian. Courtesy/ Royal Collection Trust, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

London: The early story of Bombay’s evolution as India’s commercial capital is reflected in a new exhibition, Lockwood Kipling: Arts and Crafts in the Punjab and London, which opened recently at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The exhibition, which runs until April 2, 2017, includes some 300 objects — busts, pieces of sculpture, notebooks, book covers, albums, sketches, paintings, furniture – 60 per cent of them from the V&A’s own collection.

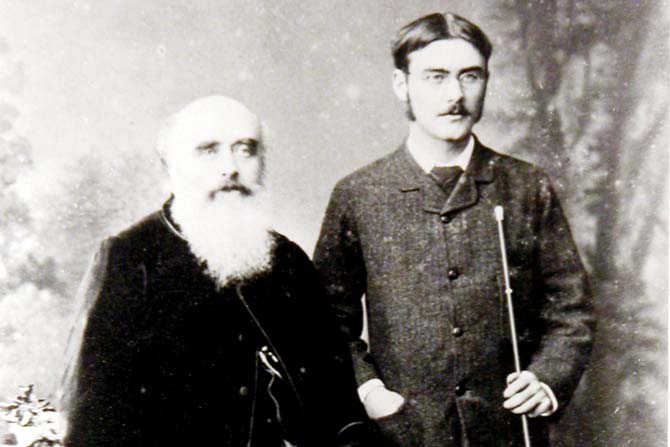

Lockwood Kipling with son Rudyard Kipling in 1882

John Lockwood Kipling was the father of Rudyard Kipling, who is familiar as the author of The Jungle Book, Kim and other stories but mired in controversy in the last decade or so over his racist and imperialist views. But, according to the exhibition’s co-curator, Julius Bryant, “Lockwood was a major figure in his own right” — and the time is considered right to rescue him from the shadows of his son.

There is some spectacular drone footage, filmed by current students of Mumbai’s Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art, where Lockwood was a teacher from 1865 to 1875.

The exhibition will continue till April 2, 2017, after which it will be hosted at the Bard Graduate Center in New York by co-curator Dr Susan Weber

What fired Lockwood’s imagination in art and things Indian was attending the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, south London, in 1951 as a boy of 14. As someone from a lower middle class family, he left for Bombay, which he saw as a career opportunity, at the age of 27. He came highly recommended by senior colleagues in London at the South Kensington Museum, the forerunner of today’s V&A, and was taken on by the British authorities in India to teach art and sculptural architecture.

When Lockwood and his pregnant wife, Alice, disembarked in Bombay on May 11, 1865, they held a “blazing beauty of a city… the finest in the world in so far as beauty is concerned”. Much later on, in his personal copy of One Hundred Bombay Notes for General Circulation — a gossip column for the British expats — Lockwood revealed his increasing love for “Bombayland”.

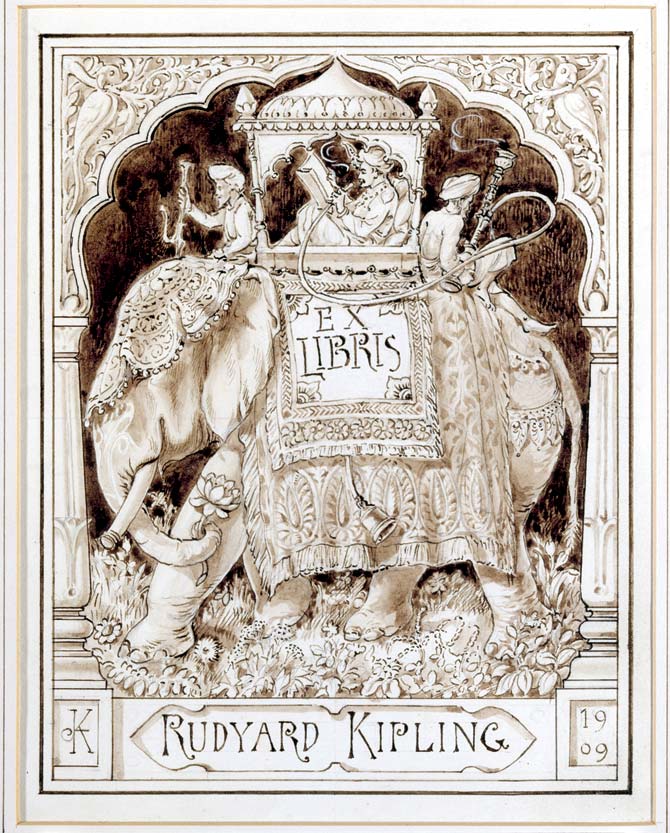

Rudyard Kipling’s bookplate Ex Libris by Lockwood Kipling, 1909. Lockwood edited his son’s manuscripts and did many of the drawings for his books. Courtesy/ National Trust John Hammond

Rudyard was born in Bombay on December 30, 1865, but was packed off at five for schooling in England. He did not return until 1882, aged sixteen-and-a-half, stayed for seven years, before departing for London in 1889 to carve out a name for himself as a celebrity author. After a decade in Bombay, Lockwood moved to Lahore for 18 years as principal of the Mayo School of Industrial Design and curator of the Lahore Museum.

Bryant’s co-curator is Dr Susan Weber, director of the Bard Graduate Center in New York, which will host the exhibition when it finishes in London. But, it wouldn’t be a bad idea for Mumbai to pitch for the exhibition, which is an offering for the “UK-India Year of Culture 2017” in the 70th year of Indian independence.

Lockwood’s contributions as artist, designer, sculptor, curator, head of a sculptural atelier and prolific journalist are set out in the immensely detailed and scholarly £40 catalogue, edited by Bryant and Weber.

In Bombay, Lockwood “contributed to the architectural decoration of the city, both directly and through the work of his students and assistants”, Bryant writes in one of his essays.

Lockwood’s “most notable commission was for sculptures for the Crawford Market, located on the same street as the art school”, he notes.

There are images of many of his other sculptural works, often in collaboration with William Emerson or his students – these include the Victoria Terminus (now the CST); the fountain at Rusi Mehta Chowk, Kamathipura; the bust of H H Khundero Gaekurar Sayaji Rao II of Baroda on the Royal Alfred Sailor’s Home (today the Maharashtra Police headquarters); the Kesowjee Naik fountain and clock tower; and the Capital of column in the staircase vestibule, New Law Courts.

Lockwood retired at the age of 53 and returned to England. Both in Lahore and later in life, Rudyard’s literary efforts were nurtured and encouraged by his father who edited his son’s manuscripts and did many of the drawings for his books.

“The characters and the flavours of India that we so appreciate in Rudyard’s books are thanks to Lockwood’s recollections,” observes Bryant.

Maybe being an indulgent father, he did not press for joint authorship.The exhibition required three years of research by Prof Sandra Kemp, senior research Fellow at the V&A, who described how Lockwood made his students go out into the villages and draw what they found and tried to instil in them a sense of pride in preserving the country’s national heritage.

“He believed they could only be great architects and designers if they understood their own heritage,” remarks Kemp.

She acknowledges that in his views on race and the British empire, Lockwood was “of his time” — a difficult issue analysed with complete honesty in the catalogue by Deborah Swallow, former Keeper of the Asian Department and Director of Collections at the V&A.

Rudyard “was popularly seen as one of Britain’s arch imperialists”, Swallow writes, adding that Lockwood was “also, undoubtedly, an agent of imperialism”.

“Rudyard Kipling’s role as an agent of empire was as a commentator — played out through the pen, articulating and shaping reader’s attitudes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,” she sums up. “His father’s role was in many ways more complex. Through his work as an artist and teacher, Lockwood Kipling created physical manifestations — sculpture, sculptural and architectural decoration, and built forms… And through his institutional role, he certainly played a key part in the creation of a cultural hinterland that continues to influence contemporary India.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!