An Aurangabad resident brings to fore a book on the history and politics of a lesser-known food tradition

Dalit thali

ADVERTISEMENT

There is a joke that commonly makes the rounds in tamasha performances in Marathwada’s villages. A crook is presented at the darbar of a king, who sentences him to death by hanging — the ‘faashi’, as it is referred to in Marathi. The crook, however, is ecstatic wondering how he could be treated to faashi and if he can have more of it. As a puzzled court quizzes him about his reaction, they learn that the crook has misunderstood his death sentence. Writer Shahu Patole explains that the crook, whose origins would be from a Dalit community, has his mouth watering at the sound of faashi — a delicacy prepared from the epiglottis of a goat — something that the so-called upper caste ministers and royalty know nothing about. In jest typical of tamasha, the Dalit has had the last word.

Jowar bhakri and a moong and shepu (dill) bhaji

Patole, who works as assistant director of the Indian Information Service in Aurangabad, recounts this tale in his book, Anna He Apoorna Brahma. It’s not that Patole has got the 13th century Marathi saint and poet Dnyaneshwar’s famous Sanskrit words wrong. “‘Anna he poorna brahma’ [meaning, food is Brahman - the all-encomapssing spirit of the universe according to Hindu scriptures] refers to sattvik food and the use of four flavours on a plate. However, the Dalits in Marathwada would have about, say, two flavours in each meal. With limited resources available to us, how could we afford six flavours? And, the food we had wasn’t even rajasik or tamasik, leave alone sattvik. Some communities were allowed to eat only dead animals,” explains Patole. It is not ‘poorna’, but ‘apoorna’ — the strange — food history of Marathwada's Dalits that Patole chronicles in his book, written in Marathi.

Ingredients for jowar and corainder balls

While community cookbooks have existed in Maharashtra for some time now — many of which made suitable bridal gifts — Dalit food culture has rarely found similar vociferous treatment. In 2010, a class of students at the Krantijyoti Savitribai Phule Women’s Studies Centre in Pune University and faculty members authored Isn’t This Plate Indian? Dalit Histories and Memories of Food. This bilingual book chronicles the food histories of 10 people from the Mang, Valmiki, Pinjari and Neo-Buddhist castes and contains recipes for dry fish preparations and sugarcane kheer. Deepa Tak, assistant professor at the centre, who was one of the researchers on this project, says, “The Dalit movement has found more impetus in the last 10 years due to online activism. But, while it focuses on politics and beef, there is more to Dalit culture. Our book was about knowledge production since food is central to Dalit autobiographies and understanding the history of discrimination.”

mutke

Patole’s book follows a similar line of thought. “While the lower castes are familiar with upper caste culture, the reverse is not true. Culture is always passed down the hierarchy,” he says.

Tarwat, a seasonal leafy vegetable

More than just beef

The mistaken identity of the faashi is just one of the various animal parts that find mention in Patole’s recipes. The tongue, fat and blood of goats and cattle too are treated in singular ways. “Lakuti is made with the goat’s blood mixed with a local homemade masala called yesur, which has 14 different ingredients including copra, coriander seeds and dagad phool (black stone flower). When prepared, the blood takes on a rich chocolate-like colour,” says Patole.

Umber or cluster figs, which are made into a bhaji. In the past, these were also mixed with jowar flour to make bhakri. Pics/Shahu Patole

The book, which came out a little before the March 2015 complete beef ban in Maharashtra, clears up a number of misconceptions surrounding Dalit food culture. One, it doesn’t homogenise the Dalits. “In 1956, when Dr Ambedkar inspired the conversion of Dalits to Buddhism and asked them to stop eating dead cattle, it was mainly the Mahars who followed suit,” says Patole.

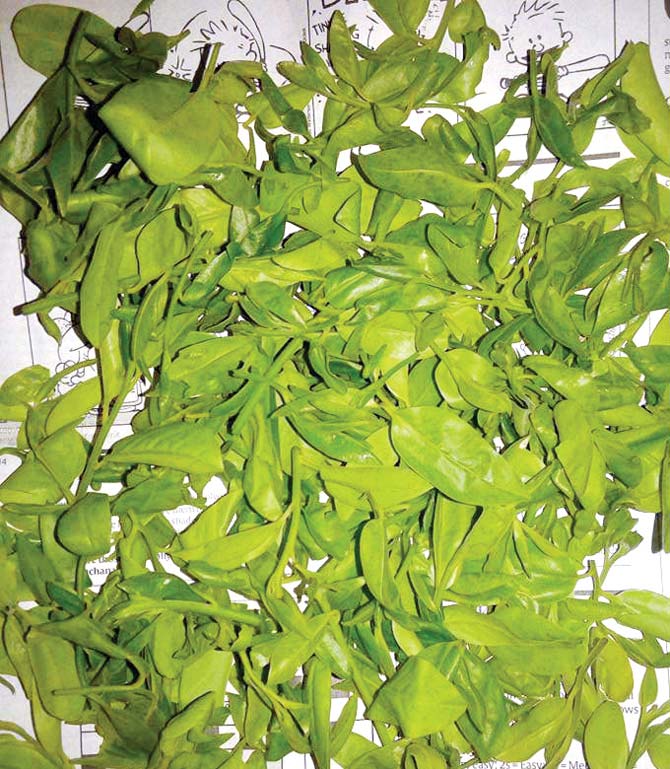

Haritpatri, a wild leafy vegetable, used to make bhaji

While beef has remained and been revived in recent months as a symbol of Dalit oppression, this controversial food item wasn’t the only meat to feature in households. The Mang community, to which Patole belongs, has a variety of interesting pork preparations, which involve roasts and pork belly, as well as mohola chi poli, made with the honey bee larvae. With non-vegetarian preparations, nothing went waste. Beef fat was commonly used as a substitute for the more expensive groundnut or sesame oil. Excess strips of beef were dried and preserved, called tanya. These were later fried or used in curry and dal preparations.

Onions being roasted to prepare yesur, a masala

Patole grew up in Khamgaon, a village in Osmanabad, but spent most of his days in a nearby boarding school. It literally gave him the distance to understand his community’s culture. Dalit foods, he observed, do not take too long to cook. “Where was the time? The men had to go to work and women had a number of mouths to feed,” says Patole. Thus, the shortest recipe in his book is to do with tender radish leaves. “We pluck them off the radish and eat them with jowar bhakri,” he narrates. “People laughed at me: How could this be a recipe? But it is true. This is what we ate,” he continues, adding the iconic Dalit vegetarian dishes use vegetables not frequently popular with mainstream Maharashtrian cuisine. Drumsticks, pumpkin leaves, cluster figs (called umber) and a leafy vegetable called tarwat are part of the Dalit thali.

Shahu Patole

Dalit pride?

Shahu Patole is working on the second edition of Anna He Apoorna Brahma and updating it with local traditions of animal sacrifice. He will be speaking on Dalit food culture in Mumbai on September 4, 5 PM at Kala Studio in Khar West. Actor Nandita Patkar will read excerpts from Anna He Annapoorna Brahma. The event is part of a series of talks called Baithak, an initiative by Kali Billi Productions.

In 1991, as a mid-career journalist, Patole sent Dalit recipes to a regional newspaper, which refused to publish them. The recipes were far too indicative of caste struggles — the recipes didn’t use much milk (since Dalits were allowed to clear away cowdung but not milk a cow); puran poli was had with jaggery water rather than the more luxurious ghee. But, times have certainly changed. Patole’s non-Dalit readers have turned to his “healthy” oil-free recipes.

His Dalit friends, on the other hand, were nonplussed when his book came out last year. While Patole feels these recipes were far too common for them, Tak points out that Dalit food culture cannot be simply categorised into a pride versus shame equation. “For the upper caste, food was a matter of pride. However, a lot of practices were forced upon the Dalits and they were later stigmatised for following them. Books like these are somewhere in a grey area between pride and shame,” she says.

Patole says the food culture of the Dalits has changed, but more starkly since 1972, when a drought in Marathwada forced out many a Mahar and Mang. “When they came to urban centers like Pune and Mumbai, their food habits weren’t limited to local and seasonal produce,” he explains, adding that he prepares a Dalit dish or two for his family for breakfast and dinner.

He recalls the case of the boiled corn on the cob. “While my children and their friends have moved on to things like pizzas, the other day, they enjoyed this boiled corn I had prepared. Little did they know that it was boiled in mutton broth — something we used to do back in our village,” he laughs.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!