Contemporary artist Owais Husain on the true meaning of identity, migration, displacement and the search for a place to call home

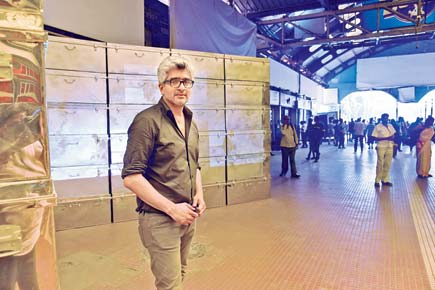

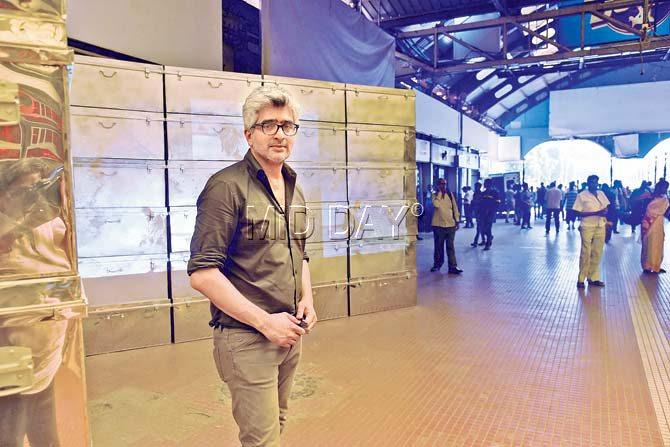

Husain likes to engage an accidental audience in a public domain. He feels public installations, like this one at CST’s platform No. 8, allow one to take art out of an institutional structure and make it part of a daily routine. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

ADVERTISEMENT

Last weekend, platform No. 8 at Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus saw a few additional trunks. They were lined up to create a wall, converging in a corner. The trunks worked as a screen for videos that talk about travel, displacement and migration.

The installation is Dubai-based artist Owais Husain’s latest work, titled You Are Forever, which looks at themes of migration, displacement and identity. The installation will move from Mumbai to Delhi this month. Excerpts from an interview.

Tell us about the installation.

It actually is a video installation. A wall of metallic trunks has been painted with reflective polish. The viewer and the location become part of the timeline of the trunks. The video on one of the trunk walls gets reflected on the remaining trunks, giving it a sense of timelessness and continuity. Trunks are synonymous with a particular meaning; they are a storehouse of memories but also symbols of movement. The video has a narrative — it is a quest that takes the viewer through the heartlands of cities. One idea is that the installation has got to do with displacement and at many levels, migration. The other idea is the search for homeland.

The themes you work on look at transition, displacement and this search for homeland.

People always had an ancestral home, a place they called home. I had no cultural context. The closest place I could call home was Mumbai; the perfect home for the homeless and the home for everyone’s dreams. For my parents’ generation, the idea of homeland was traditional. Mine was urban. My generation doesn’t consider one place to be home. We are part of a global map and wherever we move or live, even for a few years, we call that home. With the onset of the free market and the change in the urban and rural landscape, we’ve witnessed the displacement of smaller towns. It is not a tragedy happening in different parts of the world now; historically, displacement has always been there. It is just that we are more aware of it now because of the media. What we need to understand is that even though they’ve been displaced, they still have their own identity.

What does identity mean to you?

I’ve always been looking for my identity. When I was a boy, I ran away from boarding school because I wanted to become something. I was, of course, sent back. As you’re growing up, you question yourself and your origins. We look for happiness in words, action, deeds, decision-making and faith. We are all looking for happiness but we are also questioning the point of it all. Your identity is difficult to define. How can you measure it when you and everything around you is constantly evolving? For instance: the place you are from doesn’t matter because your country, your home is constantly changing. So, your true identity, in all honesty, isn’t possible to define.

You grew up in Mumbai, a place you called a ‘migrant’s dreamland’. How does the city feature in this search for identity?

Mumbai is a special place. My formative years were here. I couldn’t have grown without a city like this. With all its complexities and challenges, it was the ultimate symbolism of what modern India could become. Wherever I was working, I made it a point to return — it was basecamp. The city influenced me a lot; it has a collection of cultures from all over the country. As a city, I feel it is still rich, it’s up to the individual to gauge how much s/he is keen to explore. I used to love visiting Mumbai during the holidays, to walk the night and feel the vacuum of places like Churchgate and Fort — congested by day and empty at night.

You’re a multi-disciplinary artist. How do you balance out all these creative forms of expression?

I began my journey as an artist because I felt that this was the only way I could express myself. At nine, I was introduced to theatre, and that opened up new ideas of performance art and how a singular character can captivate an audience. At art school, I got a camera and carried it everywhere. The following summer, I was introduced to black and white cinema. In school, I couldn’t sing, so I made friends with art director and created sets for plays. When I began to make films, each shot needed to be dressed up in a particular way. I had to create an installation for every sequence — it was a marriage of different creative media.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!