For the lady who captured the nation’s imagination in her lifetime, there is little, one would imagine, that remains to be said or written

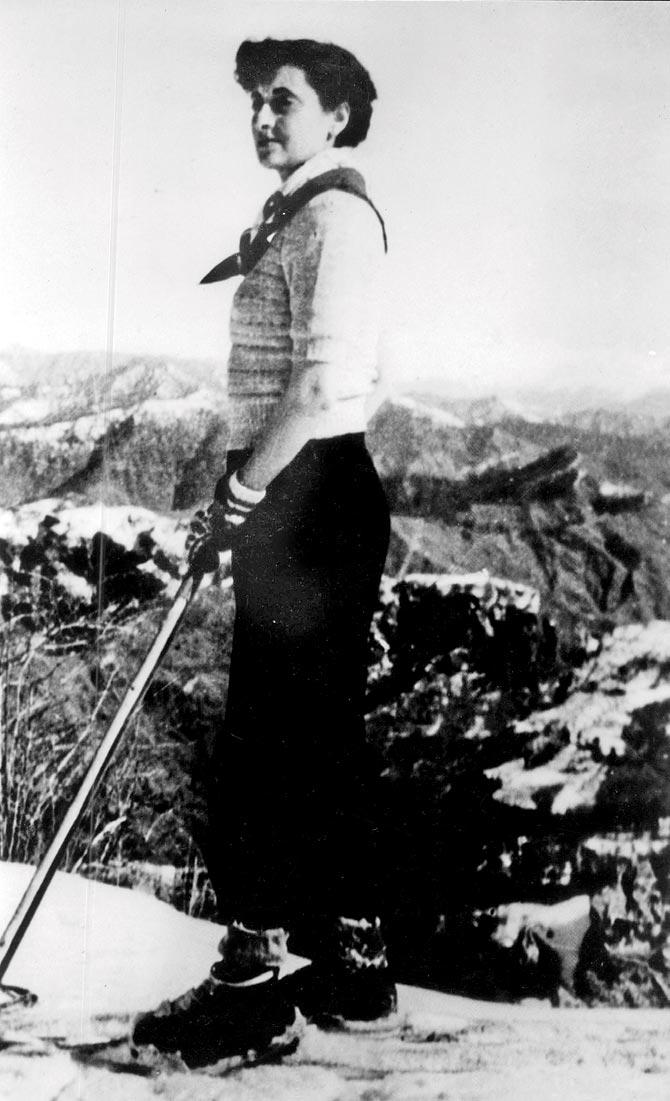

Indira Gandhi in Himachal Pradesh, 1956. Pics courtesy/S&S India

Indira Gandhi in Himachal Pradesh, 1956. Pics courtesy/S&S India

ADVERTISEMENT

For the lady who captured the nation’s imagination in her lifetime, there is little, one would imagine, that remains to be said or written. But through his book, Indira Gandhi: A Life In Nature (Simon & Schuster), MP and former cabinet minister Jairam Ramesh brings out a little-known, yet defining, facet of her personality. Ahead of its launch today, Ramesh tells us about her legacy in an email interview. Excerpts:

What gave you the idea of writing a book on Indira Gandhi as a naturalist?

Much has been written about her. But her life as a nature lover has escaped exploration and explanation. During my tenure as (Environment and Forest) Minister, I became more aware of this side of her personality. She always thought of herself as a nature lover; one of her favourite expressions was "ecological balance".

During a retreat in Melbourne, 1981

How did you carry out your research?

It took me almost five months to search archives, in India and abroad, as I wanted the book to be based on primary material — letters, file notings, messages, memos and speeches. The National Archives turned out to be a treasure trove as did the Salim Ali papers at Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Some individuals like British academic Anne Wright shared priceless letters of Indira Gandhi, like the ones on the protection of Siberian cranes to the presidents of Pakistan and Afghanistan; the

two gentlemen she wrote to actually responded to her.

Gandhi’s concern for ecology precedes the narrative on global warming. What drove her conservation initiatives?

Undoubtedly, her father had a great influence on her. But, she was instinctively drawn to nature too. She was a founder-member of the Delhi Bird Watching Society, for instance, and her letters to Nehru reveal her extraordinary interest in nature. She also had naturalist friends like Salim Ali, Billy Arjan Singh, Duleep Matthai, Anne Wright, Sunderlal Bahuguna and others who continually engaged with her.

At BNHS, with Dr Salim Ali, 1974

Tell us about the bond she shared with Dr Salim Ali.

Salim Ali had an enormous influence on her and her contributions to saving the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary and Silent Valley. She respected him and he had easy access to her. My book has many letters the duo exchanged.

Apart from Project Tiger, what are some of her policies that people know little of?

She drove programmes for the conservation of crocodiles and gharials, blackbucks, hanguls and other species. She was responsible for the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 and the Forest Conservation Act of 1980. And she set up the Ministry of Environment in 1980 and became its first Cabinet Minister.

Jairam Ramesh

Jairam Ramesh

Did this re-acquaintance with the former PM urge the economist in you to reconsider your policies?

To a great extent, yes. An eco-hawk became an enviro-dove. As MoEF Minister, while I strove to follow the ‘middle path’ conscious of the need to accelerate economic growth, I believed that my primary responsibility was to strengthen the foundations of ecological security and enforce environmental laws, without fear or favour.

How do you view India’s current environmental policies?

A lot of rhetoric, but in reality it is a dilution and weakening of the edifice of environmental regulation built up over the decades.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!