Sidelining the Kama Sutra, a new literary anthology edited by writer Amrita Narayanan, revisits 3,000 years of India’s bold and romantic erotica

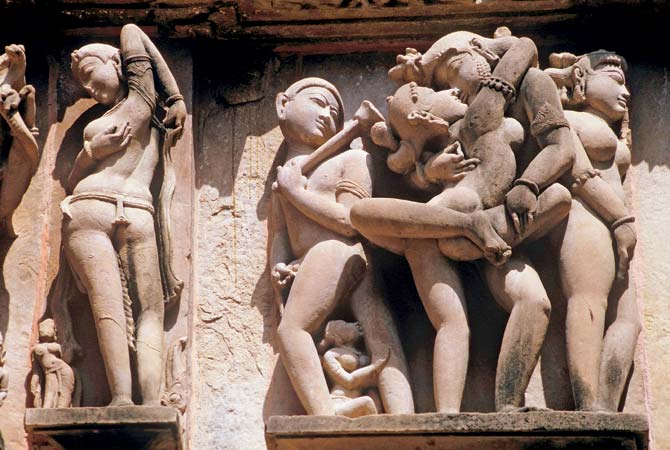

The author says that even texts like Kama Sutra, as depicted in Khajuraho, gave a nod to the traditionalist sentiment

ADVERTISEMENT

The God of pleasure was never meant to die. There were many an attempt to kill him, and classic Indian traditionalist writers did their best to get rid of him in their stories. But, the same writers nonetheless resurrected him, as if to say, though a nuisance, the erotic should be allowed to flourish, says Goa-based writer and clinical psychologist Amrita Narayanan. She is discussing kama or sexual desire in her new erotic collection, The Parrots of Desire (Aleph Book Company).

The anthology, which took two years to put together, navigates 3,000 years of Indian prose and poetry, ranging from the Vedas, the Tamil Sangam period (300 BCE - 300 AD) to the Bhakti movement, as well as colonial and contemporary works, to investigate the illuminative truth of sexual life. The results transcend the Kama Sutra, the text that is often erroneously considered synonymous with Indian erotic history.

An extract from the Koka Shastra, for instance, finds mention in this collection. Written somewhere between the 11th and 12th century, the text that Narayanan chooses from the medieval Indian sex manual describes the 'Sixteen Stations In The Body Of Your Gazelle-Eyed Lady'. "On the first day, the lover brings his girl to orgasm by embracing her neck, pressing kisses on her head, pressing both her lips with his tooth tips, kissing her cheeks, ruffling up her hair, making gentle nail marks on her back and sides…, and softly making the sound 'sit'," reads the translation. It would take another 15 days and 14 more instructions, before "a woman becomes passionate". The experience of pleasure was a serious engagement then, says the author, cultivated only with careful learning. "I think at this particular period in time, and perhaps generally, there is a tendency to deny that Indian writing has a history of commentary on the erotic. It's been made to look like something contemporary or rather, one that came from the West. I thought it would be good to set the record straight," says the 42-year-old.

This denial, however, also comes from the constant tension between the traditionalists and romantics prevalent at the time. While traditionalists worried that the erotic, if not tightly controlled, could undermine life goals, the romantics, believed that the "best life is one in which our understanding of the erotic are maximally enhanced".

"At a more playful level, I realised that [erotic] writers from several thousand years ago experienced things in similar ways as writers of today," Narayanan says.

Here, she cites a translation from Tamil Sangam poet Ammuvanar's What She Said: "Look, my bangles slip loose as he leaves, grow tight as he returns, and they give me away". "What she wants to say is that she feels depleted when her lover is gone and nourished when he returns. This erotic experience of pain and desire also finds mention in the works of Mridula Garg…you see how her character becomes weak, when her lover is not around," she says. "That sense of continuity in experience interested me," she adds.

Narayanan insists that she hasn't censored the texts that she has curated for this particular anthology. "If there were any compromises it was only in the length or the translator [of the original material]."

To make the compilation appealing, Narayanan has arranged the curated works around different erotic states of mind. From the trepidation of the first time to the delicious rapture of the subsequent ones and the ennui of steadfast fidelity, the collection has something for every kind of reader, seeking wisdom in love.

She admits that the motivation was secretly personal, too. "One of the reasons why I worked on this anthology was because so many of these texts spoke to me, and I wanted to have them all together. In fact, when I was compiling the material, I felt so happy that I could now find them [the texts] in one book."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!