Historian Vera Hilderbrand's new book traces the lost story of India's first women's combat force, nearly 75 years after a revolutionary leader made it possible

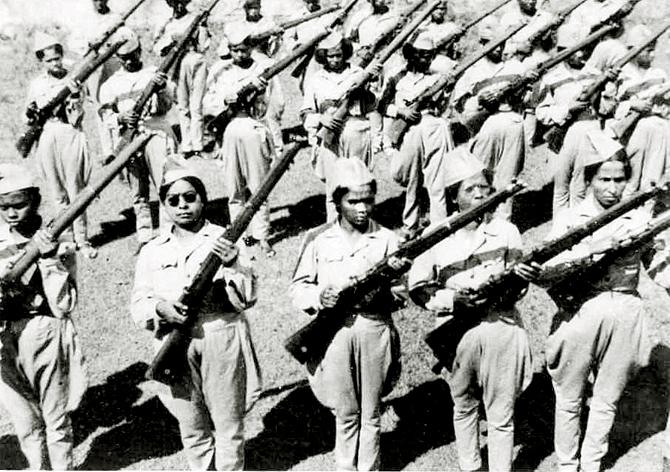

Ranis train with weapons built for northern European men in Singapore, 1944. Courtesy/Janaki Thevar Athinahappan

ADVERTISEMENT

Back in 2008, if you had asked Vera Hilderbrand why she was combing the streets of India, her guess would have been half as good as yours. On one occasion, the Danish historian recalls trudging her way through the busy market alleys of MG Road in Kolkata to find one 'Mrs Banerjee'. "I only knew that she would be more than 80 years old and was born in Burma," Vera says. Had a local shopkeeper not pointed out that the neighbourhood was brimming with Mrs Banerjees, Vera wouldn't have realised the uphill task she had at hand. Eventually, after knocking on many doors, Vera did find Karuna Ganguli Banerjee - the 'Rani' she had been looking for.

For the next three years, the historian would locate 22 such Ranis after travelling the length and breadth of India, Singapore, Malaysia and the US. Her mission: To trace the story behind the making of India's first women's military unit, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment (RJR).

Friends since their RJR days, veterans Janaki Thevar Athinahappan, Akilandam Vairapillai and Anjalai Ponnaswamy in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, March 2008. Pic/Vera Hilderbrand

Her new book, titled Women at War (HarperCollins India), which throws light on the history of these Ranis, comes close on the heels of the 120th birth anniversary of Subhash Chandra Bose (Jan. 23), the man who first made this corps a reality.

On October 22, 1943, after years of deliberation and planning, Bose inducted 150 women into this revolutionary force in Singapore. The corps, named after the iconic female war hero Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, would train for the next two years in Singapore and later fight in Burma, until it disbanded following the fall of Rangoon (today Yangon). "The creation of a female Indian infantry unit during World War II, when almost no other country allowed women in combat, was a complete surprise," says Vera, who accidentally stumbled upon the regiment on Google. "When I told people in India about the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, their reaction was, 'I did not know that. Indian women as soldiers … that's interesting.' It was then I thought it might be time to research their stories," says Vera, the wife of Robert Blackwill, former US Ambassador to India, in an email interview from the US.

While little was written about the regiment in general, Vera says her struggles were compounded by the fact that there was zero record of the women, who were part of this unit. After World War II, only Captain Lakshmi Sahgal, sister of famed classical dancer Mrinalini Sarabhai and the chosen head of RJR, became the voice of the disbanded RJR. "A large number of the male Indian National Army soldiers originally served in the British Indian Army, so after the war they were interrogated and catalogued by the British. But, the women, who were all civilians, returned home to their families without much fanfare and were not recorded in government annals," says Vera, of why the Ranis came to be forgotten. "The fact that most of the Ranis married after the war and changed their last names, made it more difficult to find them."

Having only their first names or last names, didn't help. Vera, however, managed to piece together the puzzle, mostly winnowing down on lists from computerised telephone directories, and later through word of mouth. Most of them were more than willing to speak, she recalls. For instance, when she met Rani Karuna Mukherjee, she was a widow. Her only child, a son, had died two years earlier. "It became important to her that people would know the truth about Bose and the RJR. Like several other veterans her voice quivered when she mentioned his name," she recalls.

Not everyone seemed to have shared these sentiments. A few expressed regret about being part of RJR. "The Rani, who was most outspoken in her regrets, said that she had been too young to understand the politics of Bose's approach to winning independence for India. As an adult after the war, she had come to realise that she disagreed fundamentally with Bose. Others said they had not thought enough about how they felt about taking the life of another person," says Vera.

Nonetheless, Vera feels that Bose's creation of a women's combat force was not just important for India, but for the world. "Many things did not work out exactly as Bose had hoped, but his initiative showed that he expected women to serve and take responsibility for the future of their country and culture. British Intelligence reports commented that the ranis were completely committed to Bose," she says.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!