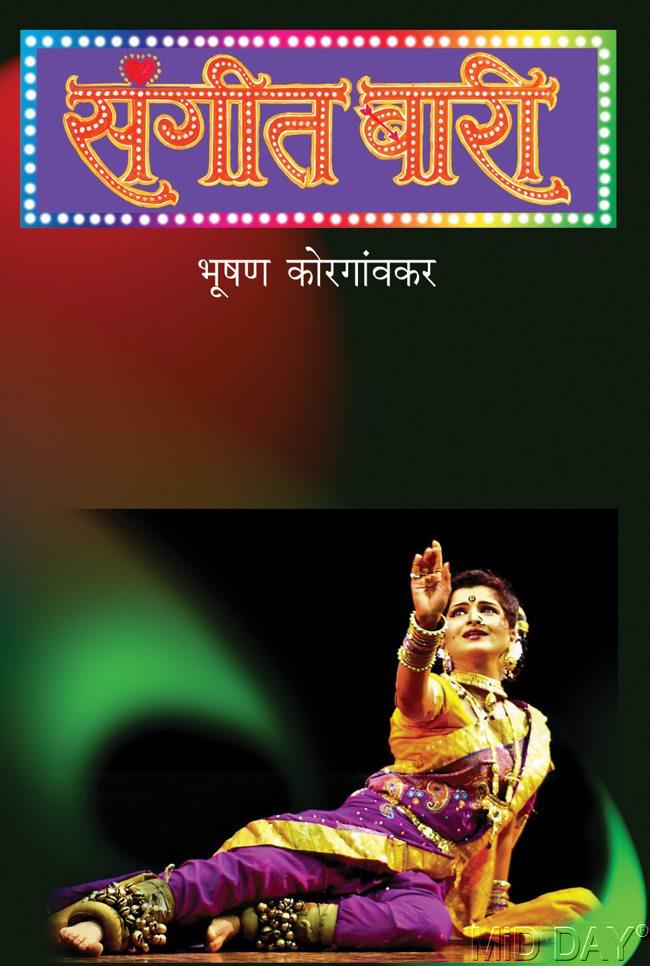

Bhushan Korgaonkar's new title in Marathi, Sangeet Bari, is an ode to the baithak form of Maharashtra’s famed lavani dance. Kanika Sharma peeks into its pages that celebrate their lives, on and off the stage

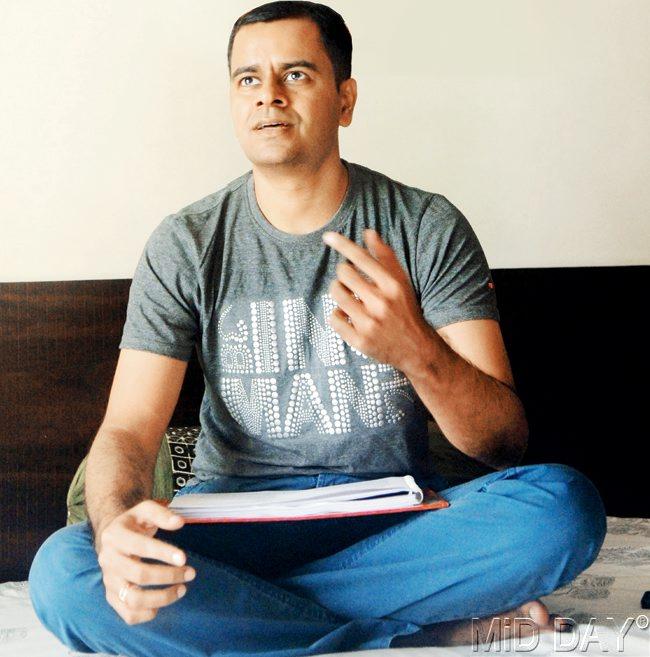

“Naka cholu joban hulahuli ga” is what Bhushan Korgaonkar, a blushing 36-year-old writer translates at his home for us — “don’t rub my breasts, they’re ticklish.” Enamoured with Lavani’s intimate genre called khaazgi baithak — Korgaonkar after spending almost a decade researching it — pays homage to Maharashtra’s art form in his book, Sangeet Bari. The reticent chartered accountant tells us, “What interested me the most was, it was written by men and written for men but it was performed by women.” And, here was a woman reporter listening.

ADVERTISEMENT

Lavani dancer Vijaya Palav performs at an event in Andheri, Mumbai. Pic/Rane Ashish

Lavani lure

In 2008, Korgaonkar along with filmmaker Savitri Medhatul had released a documentary titled, Natale Tumchyasaathi on this dance form. Six years later, he explored his curiosity further, to understand how the 16th century art form has thrived and resisted brahminicisation in the 19th century: “It flourished during the Peshwa era, having the right patronage in terms of art and money.”

Natrang Kala Kendra is situated on the Pune-Solapur Highway, at Modnimb in Solapur district. Pics courtesy/Kunal Vijayakar

But soon enough, the state got extensively ‘purified’ by 2-3% of the elite community in Maharashtra. He shares, “Bharatanatyam dancers have told me that movements done by a Lavani dancer, such as moving the eyes, chest and hips, lying down and performing are mentioned in the classical text, Natyashastra. It was dancer Rukmini Devi, a brahmin who eradicated the ‘vulgar’ movements including the eye-to-eye contact.”

Vaishali Musale Wafalekar is seen here taking blessings of ghungroos before the show. Worn with a metallic string, they are referred to as Saraswati. They earlier weighed five to six kg on one leg. It is now reduced to two to

three kg per leg.

Korgaonkar shares that in Lavani, words help in entering an ethos that is unlike the mainstream society. For instance, “Lavani dancers don’t say ‘mi sadar karte, it’s khelte,’ as it is a play. Performance would mean discipline whereas playing gives you more freedom.” He began writing his book starting with the life of Mohanabai Mahalangrekar, a 52-year-old Muslim Lavani dancer in 2006.

Varsha Sangamnerkar readies for a show

Dancer’s gaze

Korgaonkar stops midway to reveal, “Lavani dancers from sangeet bari genre don’t use their full names. They use their first name and then the name of the village as their last, and add ‘kar’ to it, such as Shakuntala Nagarkar.” Justifiably then, Mohanabai hailed from a village called Mahalangre in Marathwada. He starts the book with conversations with the enigmatic personality. “She left school in the third standard since she couldn’t tolerate the class teacher who kept on making rude comments about her caste/poverty. She threw a stone at him one day, which was the end of her school life,” the author shares. Korgaonkar draws us into her complex life where after a hiatus she achieves fame at the age of 40, an unheard of occurrence. “Her strength is singing and adakari,” he says.

Akanksha Kadam is not from sangeet bari and has no traditional background but with observation and training is Mumbai’s no 1 Lavani dancer. She’s married and has choreographed a Hindi film recently. Pic courtesy/Keya Arati;

Let the baithak begin

Korgaonkar has structured the book like a baithak, (which is one of the four types of lavani, the other being dholaki padhacha tamasha, reality shows, and orchestras) where all the sections are popular Lavani song titles — Sukumar Gulabchya Fula, Kagaz ki Haveli Hai Baarish ka Zamana Hai and others. A highlight is the writer’s meet with Padmashree Yamunabai Waikar, a 98-year-old dancer who had the Kathak maestro Birju Maharaj fall in love with her after he saw her perform.

The book soon zooms out of Mohanabai’s life to the community’s social status, music, and style of performance. The structure of the sangeet bari is intriguing: “A sangeet party is usually owned by a lady, it has seven/eight dancers along with a singer and five/six men. Thus, it’s a troupe of around 15 people,” informs Korgaonkar who also produced a few Lavani shows.

For art’s sake

Korgaonkar hopes this decorous art form has now been reduced to the item song genre. Ironically, the current lyrics have double entendre instead of being direct as they were earlier — “lageen majha tharlay maaga lagu naka an yedyawaani kahitari magu naka — ‘I know that we have had a great time but now I want to move on, don’t ask for favours as my marriage’s fixed’.” Clearly, times have changed.

Launch on: Aug 9, 4.30 pm

At: Ravindra Natya Sankul, Prabhadevi.

Call: 24365990

“Lavani dancers don’t say ‘mi sadar karte, it’s khelte,’ as it is a play. Performance would mean discipline whereas playing gives you more freedom.”

— Bhushan Korgaonkar

Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Sangeet Bari, Bhushan Korgaonkar, Rajhans Prakashan, R240. Available from August 9 onwards at leading Marathi bookstores

and online stores.

Sangeet Bari, Bhushan Korgaonkar, Rajhans Prakashan, R240. Available from August 9 onwards at leading Marathi bookstores and online stores.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!