Rakhshanda Jalil's new book brings together rare reflections on Ismat Chughtai, shedding light on a writer overshadowed by her popularity

Faiz Ahmad Faiz is presented with a book on Urdu poetry in 1978. Pic/Wikimedia commons

ADVERTISEMENT

'She does not worship upon the graves of the dead; she tells the stories of the living. She does not build castles in the air; she smelts reality in the clear light of the imagination, then pours it in the sharp and pungent acid of her language and turns it into such a life-like portrait that the reader is completely taken in by the writer's art and skill. At the same time, the reader is left ruing the state of affairs of his society. And so I am always extremely pleased when people shower abuses on Ismat Chughtai because at that time they are actually heaping abuses on themselves... Time and again, Ismat has exposed these double standards and speciousness and employed such a tremendously sarcastic manner that it pierces through these layers like a drill,' wrote noted author Krishan Chander in his foreword to a collection of stories by Chughtai.

Anonymity of fame

Translated for the first time from Urdu, this revealing insight into the work of the eminent writer, known for her fierce style, is part of a rare collection of reflections on Chughtai's life and writings in the upcoming book, An Uncivil Woman (Oxford University Press), by Rakhshanda Jalil. With essays varying in their scholarly approaches, the Delhi-based writer, critic and literary historian has brought together literature on Chughtai from scattered sources, many of them out of print, into a single volume.

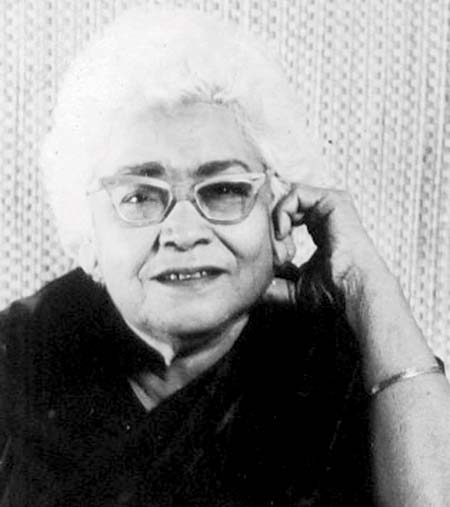

Rakhshanda Jalil

"When it comes to Ismat Chughtai, nobody has gone beyond the adjectives. She is appropriated by radicals, progressives, feminists and liberals, who may be well meaning, but there was a need for a more nuanced understanding of Chughtai's life and work. And my job was to find the voices that could do that," says Jalil about the book that features essays by Chughtai's contemporaries including Chander, Qurratulain Hyder and Faiz Ahmad Faiz, and present-day critics and writers like Geeta Patel, Tahira Naqvi and Fatima Rizvi. Apart from the essays, two interviews and critical obituaries are part of the book as well.

Besides delving into her rich collection, the research took Jalil to the rare book sections of libraries in Jamia Millia Islamia and Aligarh Muslim University, where she came across special editions of literary journals dedicated to Chughtai. "Unfortunately, many of these editions were hagiographical and perpetuated stereotypes, instead of offering critique. When you call somebody a great writer, you also need to explain why," she says.

Spotlight on the writer

Has justice been done to the oeuvre of a writer whose range of work has become synonymous with the controversial short story Lihaaf? "Chughtai was burnt by the fire of Lihaaf; something she wrote when she was very young. In fact, it was not even representative of her style of writing. When she was charged with obscenity for it, she was a young bride, who didn't want to put her family through it. But as is the case with Nabokov's Lolita or Attia Hosain's Sunlight on a Broken Column, she couldn't come out of the shadow of Lihaaf. In fact, this explains overwhelming focus on one work and the resultant popularity went against her," explains Jalil, adding, "This was the case with Manto, too, but later work on his writings freed him from these shackles. Such work on Chughtai, however, had been pending."

A victim of censorship, would Chughtai feel suffocated today? "After Lihaaf, her writing became fairly sanitised. If anything, there was a degree of prudishness to some of her works. Censorship continues to be a thorny issue. People pull out all kinds of things like sanskaar to defend a bogus argument."

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!