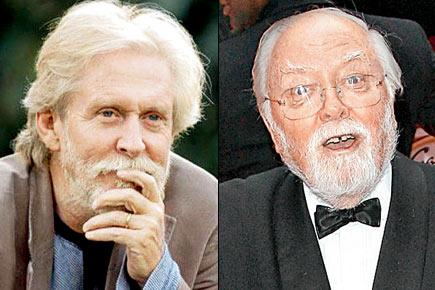

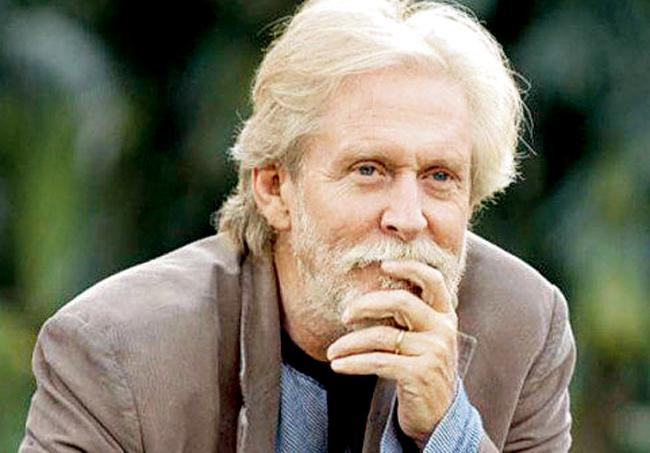

As a young, uncertain actor, Tom Alter worked with late Richard Attenborough on significant projects, and remembers the legend for his disarming honesty, commitment and a passion for the art

Richard Attenborough

His looks deceived you — twinkling eyes, roly-poly, smiling face — you took him for a favourite uncle, or a Santa Claus for all seasons. He could be all this — helpful, humble, giving — but Richard Attenborough was far, far more than he let on. He was an artiste and human being of great depth and perception, and I was fortunate to be witness to his genius and craft, and be a very small part of it. He always searched for that Bridge Too Far.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tom Alter first met Richard Attenborough in the summer of 1977 in Calcutta. Pic/Getty Images

A man of his word

We first met in Uttam Kumar’s make-up room in Indrapuri Studios in Tollygunj. It was the hot and humid summer of 1977 and the great Bengali thespian’s make-up room was the only air-conditioned one in all of Tollygunj in those distant days. It was given with much grace to Satyajit Ray and Attenborough for their collective use and I — as a humble Weston to Dickie’s Outram — was allowed into those hallowed premises, and it is there where I not only met Attenborough for the first time, but rehearsed again and again our scenes together in The Chessplayers.

Tom Alter, actor

Attenborough was very earnest, and very easy to work with. He sought perfection, and we must have rehearsed dozens of times. It was then that I heard his famous quote, that he would have agreed to work with Satyajit Ray even if the legendary director had given him a telephone directory as a script. Alas, telephone directories are now out of style, as is dedication and passion of the Attenborough and Ray mold.

All for the sake of art

It was so easy to work with him — easy in the sense of being at ease. We did our four scenes together with very few retakes, and for me, a young and uncertain actor, he was a perfect mentor. He also taught me a lesson which I never forgot. In the hot, humid and un-air-conditioned studio in the middle of a Calcutta summer, Dickie stayed back to give his cues for me off-camera — resisting, with sweating brow, the temptation of Uttam Kumar’s make-up room — when I tried to convince him that it was not necessary (almost no Indian actors, great or not-so-great, ever stay back to give cues off-camera for their co-actors). He insisted, saying that it was part of an actor’s duty and art. I was both humbled and delighted (many years later, working with Peter O’Toole, I was gifted the same grace by that legend).

It was during this shoot that Dickie spoke about his film, A Bridge Too Far, which was nearing completion, his dreams about the film, Gandhi, and how I must work with him in the latter. Having heard many such promises already during my young career in Bombay, I was delighted, but did not take it too seriously. But, once again, Dickie clean-bowled me with his honesty and commitment.

Three-and-a-half years later, I was working with him in Pune for Gandhi.

When Dickie was baffled

Two other memories of the Chessplayers shoot come to mind. As we shot our first scene together — the major scene between us, in English — Ray would need only one take, leaving Attenborough baffled. Finally, Dickie asked me whether he thought there was actually film in the camera (yes, films used to be made on film) or whether Ray was simply rehearsing the entire scene, and would actually shoot it later.

I told him I was as baffled as he was. After about 10 shots, all one-takers, and no comment from Ray at all, we both thought Dickie’s hunch was correct. Then, suddenly, Ray called Outram — Dickie — into a corner, a few words were shared, and a smiling Attenborough emerged. Now I wondered when my moment of glory would come. It did, very soon after. I was called into that same corner and the words I heard were simple and heart-warming — “Tom, you are doing just fine. Keep it up.” Aah, those were the days.

At a press conference held during the shoot, Aparna Sen asked Attenborough how he, as a director, dealt with his actors on the set. “Every person in my unit has only one job — to keep my actors happy and at ease and inspired,” replied Attenborough.

Attenborough and Gandhi Later, while I shot — albeit briefly — for Gandhi, I realised those were not mere words. Dickie meant it with all his heart. Till date, I have a way of praising both Anthony Hopkins and Dickie — I have always said that Anthony Hopkins is Richard Attenborough with a scowl.

Naseer (actor Naseeruddin Shah) was very, very keen to play the role of Gandhi (one of the great actor’s lifetime dreams, which came true many years later). He and I met Attenborough, and the director took great interest in Naseer, even calling him to London for a screen test. However, at the end, of course, Naseer was not taken. My feeling is that Naseer would have made a superb Gandhi in the film, but it was a decision Attenborough took with immense concern and care. It all reflected the man’s passion and commitment.

Outram sahib, your Weston gives his final salute with love and so many fine memories. As Weston quoted Wajid Ali Shah’s couplet to Outram, I do so to you — ‘Wound not my bleeding body, throw flowers gently on my grave. Though mingled with the earth, I rose up to the skies. People mistook my rising dust for the heavens’. Khuda hafiz.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!