The Indian film industry has captured labour issues in several films since the 1950s. In recent times, however, the work force has disappeared from the Bollywood scene

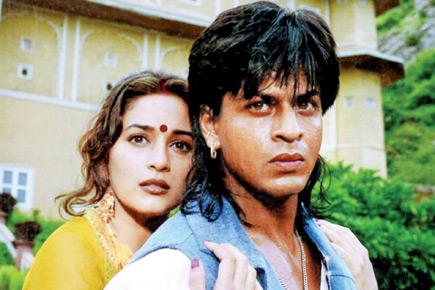

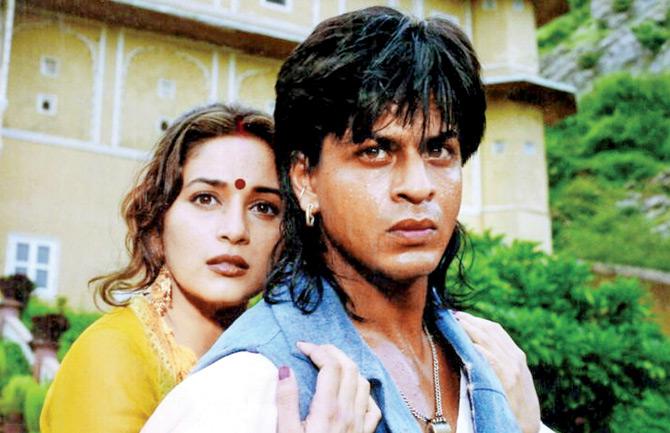

Madhuri Dixit and Shah Rukh Khan featured in Koyla (1986), which focused on bonded labour

ADVERTISEMENT

One of noted Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s couplets states:

Hum mehnatkash jagwalon se,

Jab apna hissa mangenge,

Ek khet nahin,

Ek desh nahin,

Hum saari duniya mangenge.

Madhuri Dixit and Shah Rukh Khan featured in Koyla (1986), which focused on bonded labour

These lines succinctly state that when those who toil will ask for their share, it will not be a piece of land, but the world.

Workers of the world, unite! is one of the most famous rallying cries from The Communist Manifesto (1848), by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Considering the importance of the labour force, they should reign the world, but the reality is different.

The Indian film industry has captured labour issues in several films since the 1950s. Films like Naya Daur (1957), Paigham (1959), Namak Haram (1973), Deewar (1975), Kaala Patthar (1979), Coolie (1983) and Koyla (1987) have highlighted the changing face of labour and their plight.

The Rakhee Amitabh Bachchan starrer Kaala Patthar (1979) highlighted the plight of coal mine workers

Changing face

In recent times, however, the work force has disappeared from the Bollywood scene. The saga of a poor labourer may not have big studios picking up such projects. In the past, filmmakers used to give more importance to burning social issues. The scripts had the protagonists belonging to middle -class families. Nowadays, the hero is portrayed as a larger- than-life persona. His family lives in a sprawling mansion. And his mother does not stitch clothes for a living.

Raj Babbar, Nanda and Dilip Kumar in Mazdoor (1983), which took a look at factory workers

Mirror to life

Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! (2008) and Shanghai (2012) writer Urmi Juvekar explains, “In the ’60s and ’70s, cinema and literature were used by audience and readers as a medium to find answers to their social, national and life’s problems. Now cinema and literature are generally used for escapism. This is the reason that real-life issues have been marginalised. Emotions have become mechanical. People from different strata only ask cozy questions. This gets reflected on screen.”

“Where mills once stood, industrial units, shopping malls and multiplexes have been made. Construction work has become mechanised causing a reduction in labour hands.

In a way, the labour community itself has become extinct. So filmmakers feel the subject may not have any connect now,” says Hindi film journalist Vishnu Khare. Explaining the lack of the labour class in films today, cine historian Jai Prakash Chouksey says, “The heroes of today are capitalists, so the labourers and the farmers are missing from stories.

Liberalisation altered middle-class values. That class is now all about upward mobility. The struggles of the people at lower economic level does not inspire filmmakers.”

The few times that they do crop up on celluloid, they need to be made attractive for buyers. As Masaan (2015) director Neeraj Ghaywan explains, “Even when we portray harsh realities, we have to glamourise it. In Masaan, we had to add a sequence of kids diving into the river to retrieve coins featuring actor Sanjay Mishra. The attempt was to lighten the movie. However, this is not the case in Bulgaria or France as big corporates support grittier films. It is due to this that a film like The Lunchbox (2013) got a French co-producer.

In Peepli [Live] (2010), the labour migration was commercialised even though it dealt with a serious subject.” Veteran filmmaker Govind Nihalani says, “Trade unions have died, labour laws have become redundant. The Left parties have lost ground and they are only talking about wages and salary. The media is also not cooperative towards the labour class. Since the labour class is disappearing, there is no discussion about them. The word ‘labour’ is finished. History is an eyewitness that there is no effort to preserve what is going extinct.”

Filmmaker Chandraprakash Dwivedi opines, “Till the ’80s, films portrayed social concerns, but later it became all about entertainment. Movies about issues were classified under the parallel cinema movement, which was not supported by the market. The market changed the habit of cinegoers. Cinema became a product like other saleable products. Its slogan became that cinema’s sole aim was entertainment, entertainment, entertainment. So where does the labour force fit in? The labour force has neither a purchasing capacity nor does it stir any emotion in the audience. In my film Zed Plus (2014), I made a mistake because the hero was a mechanic who sat at his shop wearing a lungi. That was not catering to the audiences’ taste — it was not upmarket. We did not get screens even at primary levels, forget the rest.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!