What happens when fashion partners call it a day? How do you carve a different identity while continuing to share an aesthetic language? It takes serious work, we find out

Armaan Randhawa and Aiman Agha take a bow at the end of their Lakme Fashion Week 2014 show in Mumbai; Their March 1, 2016 Facebook post announced the label was now simply called Aiman

Sometime last week, the flavour of the indie-crowd, designers Armaan Randhawa and Aiman Agha, who designed under the label Armaan Aiman, split. It was a short association. The duo, first showed at GenNext at Lakmé Fashion Week (Winter/Festive) in 2013 and soon gained entry into the cool and quirky crowd; Neha Dhupia, Kalki Koechlin, Athiya Shetty and Anushka Manchanda wore and swore by their designs. Their clothes were modern — clean-lined dresses, bomber jackets with embroidery inspired by psychedelia and wild animals.

Sometime last week, the flavour of the indie-crowd, designers Armaan Randhawa and Aiman Agha, who designed under the label Armaan Aiman, split. It was a short association. The duo, first showed at GenNext at Lakmé Fashion Week (Winter/Festive) in 2013 and soon gained entry into the cool and quirky crowd; Neha Dhupia, Kalki Koechlin, Athiya Shetty and Anushka Manchanda wore and swore by their designs. Their clothes were modern — clean-lined dresses, bomber jackets with embroidery inspired by psychedelia and wild animals.

ADVERTISEMENT

Armaan Randhawa and Aiman Agha take a bow at the end of their Lakmé Fashion Week 2014 show in Mumbai; Their March 1, 2016 Facebook post announced the label was now simply called Aiman

Then on March 1, their Facebook page had an update — a model in a long-line pastel kurta and churidar announcing the label was now simply called Aiman. Agha refused to comment on the split. Randhawa says the reasons are personal and they remain good friends. "I have some family problem to attend to… a family business that needs my attention," he says.

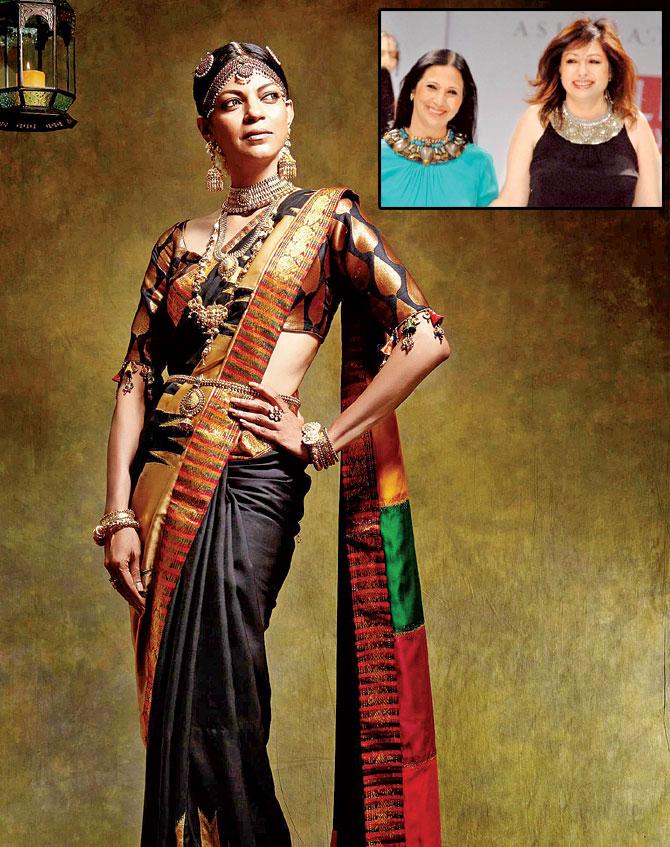

A few weeks earlier, Delhi-based designer Leena Singh and Ashima Singh ended their 24-year-long association. Ashima-Leena, as the label is still called, is a luxury and pret brand, specialising in ethnic and luxury resort wear. Both keep a dignified silence on the reason behind the termination of the collaboration. "You cannot be together for 25 years without mutual respect and solidarity," says Leena, "and we still maintain that integrity."

Older splits

Though rare, the breaking up of design partners is not uncommon. In 2005, when Stefano Gabbana and Domenico Dolce ended their romantic relationship, they kept their professional one alive for the sake of a îu00c2u0082u00c2u0080600 million turnover. On the Indian scene, Rahul Mishra and Samar Firdaus, both students of the National Institute of Design, debuted as partners in 2007 at Lakmé Fashion Week. A year later, they were designing independently. The official reason: Firdaus needed time off to pay attention to the family business.

Rahul Mishra, the Indian toast of the international circuit since he won the International Woolmark Prize 2014, split from partner Samar Firdaus a year after they debuted in 2007

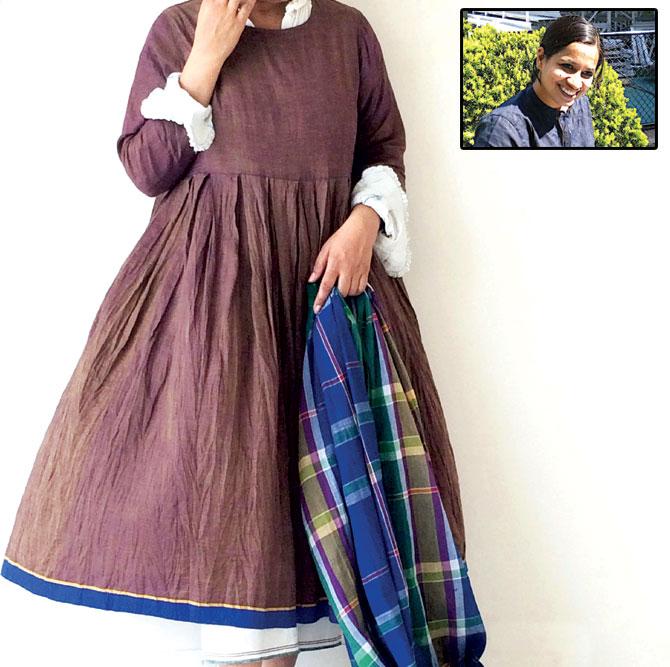

Aneeth Arora and Chinar Farooqi, both from Udaipur, also debuted as GABA in 2008, but in June 2009, Arora was designing independently as péro. Farooqi launched Injiri in the same year. Neither talk about the reason behind their separation but it was seemingly because they wanted independent control of their vision.

Both labels still carry the same DNA: Clothes crafted from handloom fabric in the traditional way — cut such to have very little wastage of fabric, characterized by edges, banners and surface detailing. Farooqui first trained in Fine Arts before she moved to Textile Design at NID. In this domain, she found her niche and while a bulk of her sales can be attributed to Dubai, Europe Korea and Japan, the Home line that's close to her heart. "As an artist, the Home line gives me a canvas to make compositions," she says.

The confusion

"Any partnership is a balance of Yin and Yang," says event producer and brand consultant Ramesh Menon. "Design and the marketing process blend to find a singular voice. Disagreements usually occur when one partner thinks s/he is putting in more work and receiving less appreciation, visibility or share in profits.

Ashima Singh and Leena Singh maintain a dignified silence on ending their 24-year-long association. While Leena will retain the original brand, Ashima soft launched her new independent label in Delhi recently

When partners split, sometimes only one of them survives and thrives. Usually, it's harder for the breakaway brand to establish itself as something more that a 'me-too' brand."

This in part, is because the seed of the partnership is a common, shared aesthetic language that can't be divorced from either designer. So there is confusion among clients, a resistance from retailers in stocking similar- looking pieces. "In India, designers mostly still take care of the end-to-end process of the business — client and retailer relationship, marketing, production and design," says Menon. "There is no corporatisation of any part of the process. So, to come back into the same arena, they rely on the same relationships and that can be difficult."

Chinar Farooqi and Aneeth Arora debuted as GABA in 2008, but in June 2009, Arora was designing independently as péro. Farooqi launched her independent label, Injiri. Observers say their clothes carry the same DNA

"There always has to be a balance for a partnership to work," says fashion mentor Sabina Chopra. "Sometimes, the partners grow in different directions and there is no synergy left. One person feels that only one of them is able to do a better job. Or perhaps one of them is more ambitious or creative than the other."

However, Menon points out, these difficulties are also faced when a junior designer assists a better known designer for a while and then starts his or her own label. The clothes may look like a 'copy' because the assistant used to do most of the work for the parent label. It is also the case when a designer becomes the creative director of another brand. "Sometimes, the less successful of them is accused of copying the other brand, but they are doing what they have always done," says Chopra. "The way to stand apart is to do what you do with authenticity."

Menon is optimistic that the labels can carve a different clientele or market for themselves, instead of diluting the original brand's identity, like in the case of Raakesh Agarwal who used to assist Tarun Tahiliani.

Next blueprint

In the case of Ashima-Leena, Leena will retain the brand. "It will be the same brand, doing the same design and serving the same clientele that we have for 23 years," she says. Ashima is carving out a new identity and has already launched her collection under Ashima Singh at Delhi's Visaya hotel. "A more formal launch is scheduled during the wedding season, and then a presence in Mumbai," she says "But I have no fashion weeks planned as yet, however, going with the flow, I may just surprise myself!"

Asked how she will combat brand confusion, she says, "It will be a little different, but I have always designed from the heart. Along with couture, which will remain my first love, there will also be more easy pret and semi-casual pieces with digital printing. There will be season-specific handlooms too — I am working on ivory Chanderis and Maheshwaris for the summer."

She admits it will be a challenge to define a new brand but hopes that she can develop an edgy niche for herself in the market. Farooqui likes to keep away from the fashion week circuit, supplying to select retailers such as Bungalow 8 in Mumbai, Amethyst in Bangalore and Jaipur Modern in Jaipur directly.

"The aesthetics/design philosophy is similar," she says. "However, I am more textile oriented. I believe in slow fashion and don't relate to the fashion week scene. I like to be quiet and am happy in the way the brand has grown. I know what I have been able to achieve with my own work. Most importantly, it helps me achieve my dream of combining textile design with art." Industry insiders say she has made a conscious decision of never looking at what péro was doing so there would be no overlap, confusion or influence.

Randhawa is focusing on the Autumn/Winter season that comes up in August, when his designs will be available at Ensemble and Ogaan. Instead of the Indian fashion week scene, he has set his eyes on New York. Since they have no investors — the business is client-based — they didn't have to think about staying together for the brand.

And for fashion buyers, maybe two is better than one?

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!