When Anglo-Indian businessman Ernest Timothy McCluskie founded McCluskieganj, it was to be the promised land of the Anglo-Indians. Now near ruin, this town in Jharkhand is the subject of filmmaker Paul Harris’ documentary, Dreams of a Homeland

Australia-based Anglo-Indian filmmaker Paul Harris walks one through a sleepy town in Jharkhand, a one-time flourishing homeland for the community, which is now near ruin.

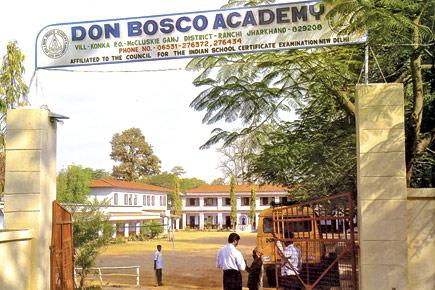

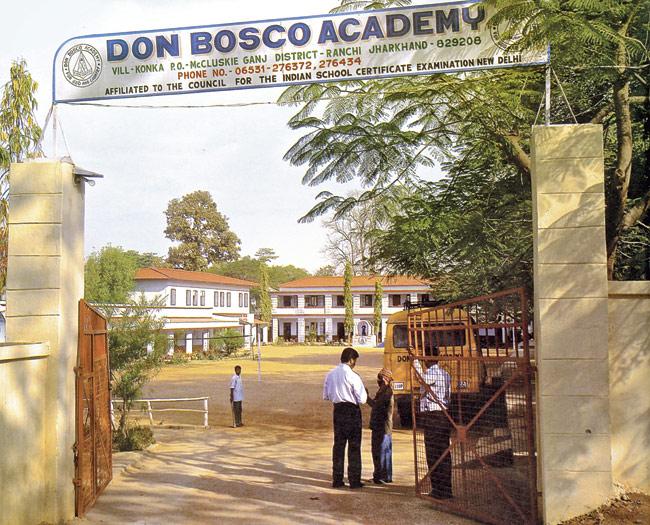

The school is owned by an Anglo-Indian, Alfred de Rozario

In this email interview, Harris spells out why his documentary on this colony, Dreams of a Homeland, acts as an invaluable treasure, and a reminder of the fast-vanishing legacy of the Anglo-Indians.

The Interview:

Why did you decide to embark on this unique project?

In 2010, I was filming and researching material for a project called End of the Raaj a history of Anglo-Indians. The attempt was to trace the social and political history of the Anglo-Indian community, from 1498 with the arrival of the first Europeans to 1947 when India became an independent nation.

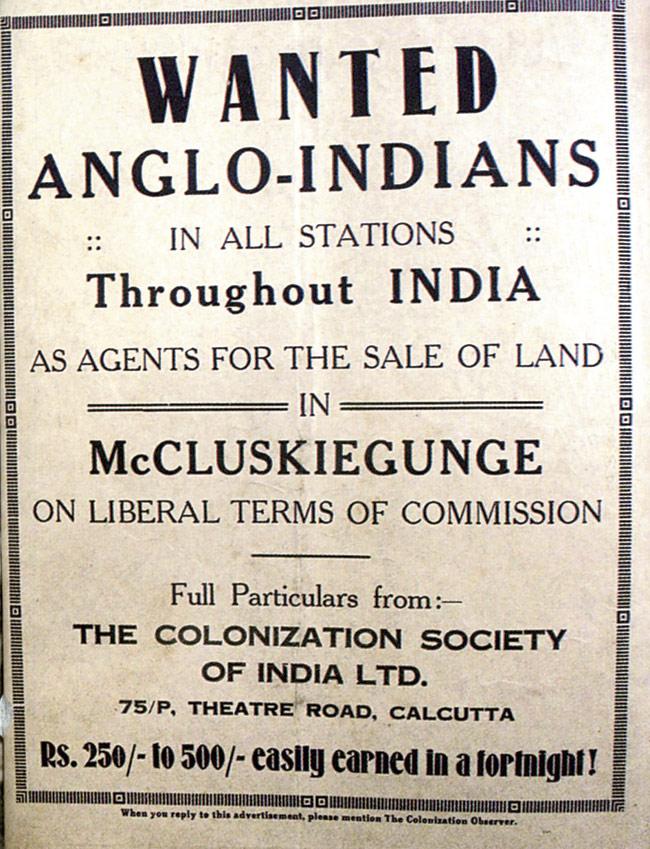

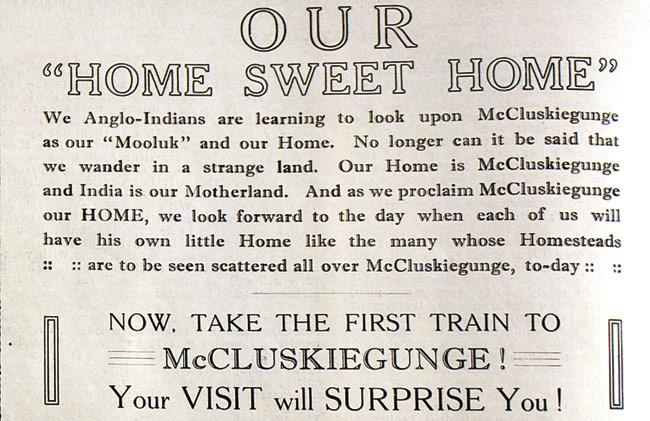

These advertisements were published in the magazine, The Colonization Observer

During the course of my research and travels, I visited McCluskieganj, a small town in Jharkhand. This town was the brainchild of Ernest Timothy McCluskie, an Anglo-Indian businessman from Calcutta. It was established in the 1930s as a settlement for Anglo-Indians, a sort of “homeland” where Anglo-Indians could come and settle.

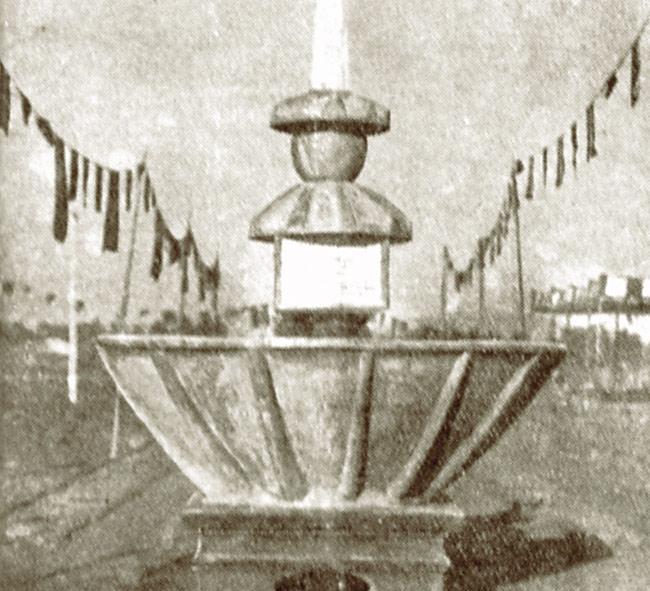

This monument was built by the settlers of the colony after the death of the founder Ernest T. McCluskie. Today, the monument lies uncared for and abandoned

I was fascinated by the place and thought to myself that this town deserves to be documented as a separate project, rather than just be a chapter in my documentary End of the Raaj. In 2012, I had an opportunity to return to the town to make this film, called Dreams of a Homeland.

How have you funded this project?

The film has been self-funded. Initially, I had tried to raise funds for End of the Raaj but with no success. Of course, many have promised help and support but none have delivered except for about five individuals who have made small financial contributions in their personal capacity. I decided to go ahead and self-fund the project and then hope to recover my investment through the sales of books and DVDs or even try to sell the project for broadcast to television channels.

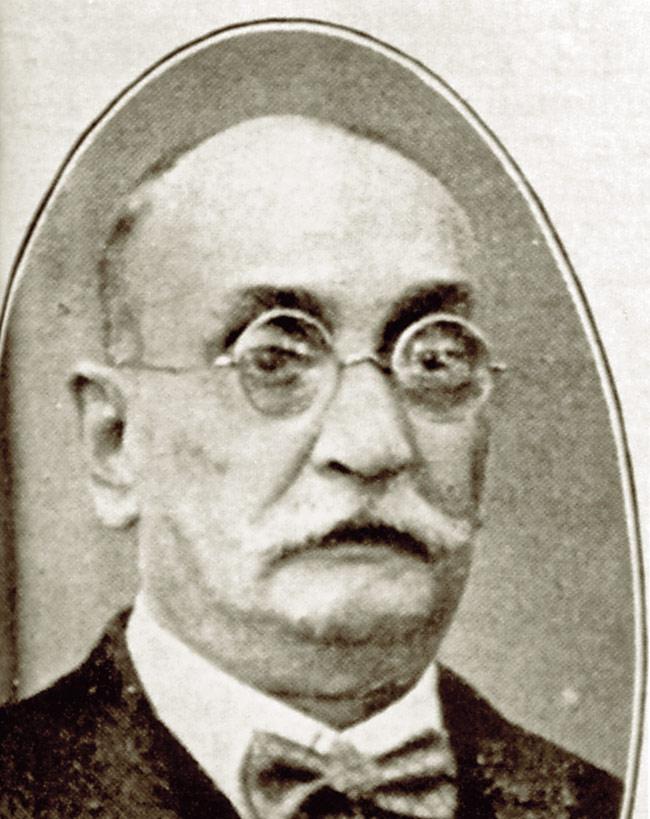

Paul Harris behind the camera

What was going through your mind as you approached the end of the documentation? What kind of learning and unlearning did you have to face?

Everything about McCluskieganj was new, so I did not have to “unlearn” anything. The process that began with my first visit in 2010, when I had interviewed and filmed footage in McCluskieganj, opened my eyes to the existence of this town. It was such an important part of our community’s history and yet few were aware of its existence.

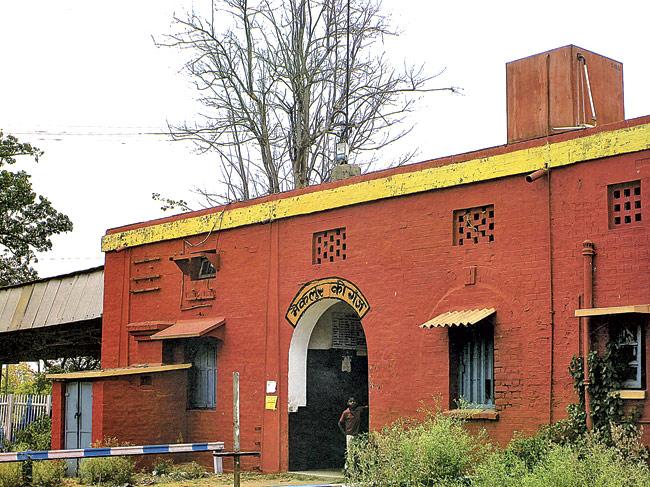

The McCluskieganj Railway Station with its old-world charm

Even Anglo-Indians didn’t seem to know much about the place, except for those in neighbouring towns and cities. As a child, I grew up in a small railway colony called Gomoh, roughly 100 miles from McCluskieganj, and though I had heard about the existence of this town, I did not know much about it.

The whole project has been an eye-opener; what fascinated me the most was that in the 1930s a group of people actually came from various parts of the Indian sub-continent and had a go at forming a colony. They were actually successful for the first 10-15 years. They were real pioneers and I dedicate the book and film to the spirit of those pioneers.

Sitting in the homes of McCluskieganj, what sense did you get of their stories, their lives and a lost legacy that the world is only now waking up to?

A thought that was always in my mind while in McCluskieganj was, what would the place be like if it had continued to grow and flourish as it did during the first few years? Hearing the stories of some people who had been born there and lived all their lives, I was amazed at their existence.

Tucked away in a quiet corner of India, they tried to lead a rural lifestyle with agriculture being the main economic activity. At the same time, it was also a bit sad to see the current condition of the town. There is hardly any economic activity, with some coal mining and the Railways providing most jobs.

In the last few years, the establishment of some residential schools has been a saving grace and many families now provide hostel facilities for the many “out-of-town” students that come here looking for an English medium education.

What were some of the unforeseen challenges that you faced after arriving at McCluskieganj?

McCluskieganj is a tiny town where not much happens, so it was fairly easy to go around filming material without much interference apart from the normal curiosity of local onlookers. One of my biggest challenges was the heat.

I spent over two weeks in McCluskieganj during the height of the 2012 Indian summer; we shot from 6am to 10.30am, after which it was too hot to be outdoors. We had to spend the afternoons indoors, and then film again from about 4pm to 6.30pm after which there wasn’t enough light. So, planning to shoot the various sequences was difficult, and my biggest challenge.

How did they react to your project? Did they open up to you instantly, when it came to sharing information and getting a pulse on the present scenario?

Many McCluskieganj residents have grown used to being interviewed about their lives over the years, as journalists have visited the place and documented its stories, though very few have covered its history in depth. I had visited McCluskieganj in 2010; I met a few people during that trip and so, on my second visit, it was easier to re-establish contact.

Moreover, a friend whose father has established one of the large schools in McCluskieganj, the Don Bosco Academy, accompanied me, and being with this known figure helped open many doors. I was interested in the early history of the town and I could not find anyone with living memory of McCluskieganj since its inception in the 1930s.

Most people I spoke to gave me information about events in their lifetime, dating to the 1960s and ’70s. A lot of my information came from a magazine that was published in the 1930s by The Colonization Society (the organization that spear-headed the establishment of McCluskieganj) called The Colonization Observer. The magazine has a fantastic record of the colony’s events from 1934 to 1944, and was a source of excellent material for the film.

Do you plan to work on similar such projects about Anglo-Indian settlements elsewhere?

There is no other settlement like McCluskieganj, and so it is fairly unique. There were other similar settlements planned but none on the scale of McCluskieganj. Whitefield, on the outskirts of Bangalore, is probably the closest as far as establishing a colony exclusively for Anglo-Indians gets.

There were many small towns, especially towns that grew along the various railway lines, in the early 20th century with a high percentage of Anglo-Indian families, who were employed on the Railways, but these were unlike McCluskieganj which was established as an exclusive homeland for Anglo-Indians.

How important is this work for “Anglo-India”?

Anglo-Indians are a tiny, microscopic community when compared to the population of other Indian communities and it would be very easy to get lost within mainstream Indian society.

Like most parts of the world and definitely in India, many communities have been assimilated into and are now part of mainstream Indian society; Anglo-Indians are no exceptions.

With a mixing of different communities with caste, culture and language no longer being a barrier compared to earlier times, society tends to become more homogenous. Along with this, there is a loss of many traditions and customs.

With younger generations being part of a new globalised culture, the past tends to get forgotten and there is the danger that history too could get lost or forgotten along the way.

While accepting that we must move forward, and change with the times, it is important to preserve history for future generations and have a sense of knowing about our past. Dreams of a Homeland is my small attempt in preserving this aspect of the history of our community.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!