Up until the 1950s, the city’s municipal corporation followed Bombay Time (GMT +4.51) while the rest of the country had switched to IST (GMT +5.30). Two historians and a photographer do a total recall of how the megapolis followed three time standards — Bombay Time, Madras Time and Port Signal Time — all at once

The battle of the clocks: In 1905, if the clock tower of Crawford Market struck 12 noon, it meant it was 12.39 pm at railway stations in Bombay City. That was the difference between Bombay Time and Indian Standard Time. It was also the city’s way of refusing to bow down to the coloniser. Photograph of crawford market (2004). Photographs courtesy/Chirodeep Chaudhuri

ADVERTISEMENT

In the 1960s, when Australian scholar James Cosmas Masselos came to Mumbai to study its urban history, a phenomenon that piqued his curiosity would unravel a serious yet comical facet from the city’s past. Back then, if you turned up late for appointments, it was not uncommon to blame your tardiness on “Bombay Time”. While the Indian sense for punctuality (or the lack thereof) has been the rue of countless meetings and the subject of many jokes, the excuse-makers didn’t quite know the back-story to their excuse. Only half-joking, Masselos says that he dug deep into documents at the Maharashtra State Archives at Kala Ghoda, and, in London, at The India Office Records — the archives of the East India Company and pre-1947 government of India.

“It was a fascinating story and just a bit funny too,” says Masselos, who was in town over the last week. His research, originally presented in a conference held by the Maharashtra Studies Association in 1991 and published as ‘Bombay Time’ in 2000 as part of an anthology of essays titled Intersection: Socio-Cultural Trends in Maharashtra, revealed “the battle of the clocks” that raged in Bombay from the 1870s. Today, the fact that 10 am at government offices and 10 am at CST mean the same thing is thanks to the fact that we don’t follow Bombay Time anymore. What’s more, a little before 1900, Bombay’s clocks and time signals were an amalgamation of three standards — Bombay Time, Railway Time (also variably called Madras Time and Indian Mean Time), and Port Signal Time.

Sassoon Dock, 2016: Clock towers, such as this one, were most likely to have followed Bombay Time. But, there was another standard called Port Signal Time, for international ships that docked on the city’s eastern coast

Your great-grandmother might have known this. In the 1880s, the decade after the three major railway lines were connected in the Indian subcontinent, you could travel directly from Bombay to Calcutta or Madras — provided you boarded your train on time. It may sound like the most obvious thing to do, but, in those days, the Great Indian Peninsular Railway and the local bazaar clock tower followed different time standards. The clock tower would indicate 10 am Bombay Time, which meant it was 10.30 am Railway Time at Boree Bunder (later replaced by Victoria Terminus, now CST). ‘Bombay managed to quite easily to operate with two concurrent times. Travellers merely had to remember to leave half an hour early by Bombay Time to catch a train by Railway Time,’ writes Masselos in his essay. Among those who didn’t keep track was Sir James Fergusson, the Governor of Bombay from 1880 to 1885. He was said to have missed trains twice because he failed to note the difference between Bombay and Railway Time.

Bomanji Hormusji Wadia Fountain, Fort, 1998: All market clock towers were controlled by the municipal corporation and therefore showed Bombay Time. So was the case with this clock tower too, which recently underwent restoration

Specially apart

Last week, on January 6 and 7, the Department of History, University of Mumbai, collaborated with two foreign universities to host an international conference, titled ‘Power, Public Culture and Identities: Towards New Histories of Mumbai’, which paid tribute to Masselos’ half-a-century worth of work in South Asian urban history. One of the speakers at this conference was Shekhar Krishnan, a post-doctoral research fellow at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. With new insight through the Maharashtra State Archives, archives of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai and the Mumbai Police, and recalling Peter Galison’s book, Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps, Krishnan presented ‘Turning Back the Clock’, which furthered Masselos’ research into the chaotic realm of time in erstwhile Bombay. His research is part of a larger upcoming book, on time, space and currency, to be published next year.

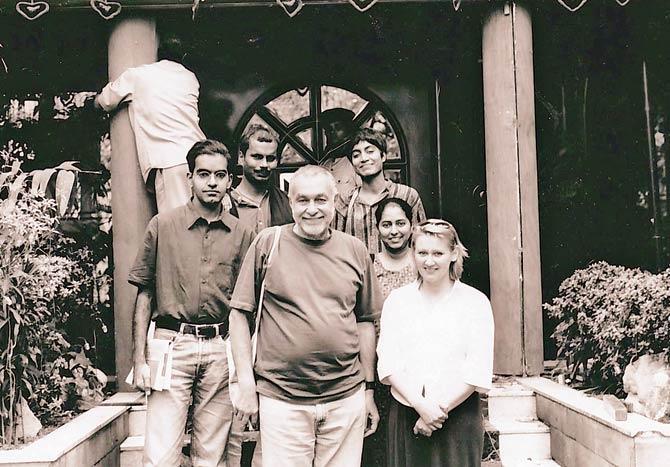

Australian scholar James Cosmas “Jim” Masselos (centre) wrote about Bombay Time in 1991. Historian Shekhar Krishnan (left) updates Masselos’ research in a new study. This photograph was shot circa 1999-2000 by historian Abigail McGowan

When we meet Krishnan at his Matunga study, he explains that Bombay Time — which was based on the movement of the sun — was followed only in Bombay City, up to Sion and Mahim. On the other hand, the railways, telegraphs, Suburban Bombay, and most other parts of colonial India, followed a unifying standard set by the longitude of the Madras Observatory.

St. Thomas Cathedral, Horniman Circle, 2016: The results of the confrontation between the local corporation and the colonial rulers were ambiguous in certain institutions. The Cathedral clock showed Madras Time but its bells summoned the faithful to prayer on Sundays according to Bombay Time

But, Bombay just wouldn’t follow suit. So, while Madras Time followed GMT +5 hours 21 minutes, Bombay Time was GMT + 4 hours 51 minutes. “Bombay people thought they were special,” Masselos tells us, adding, “And they still do. There was a degree of rivalry, not just between nations, but also between cities and presidencies. Bombay didn’t want to follow Madras’ time.”

However, these two competing standards weren’t the end of the city’s tryst with time. There’s more. Port Signal Time was followed by the naval ports and dockyards on the eastern seafront. The transmission of time to boats in the harbour by sight was by a now-obsolete mechanism called the time ball. A large wooden or metal ball would drop at a predetermined time to help international ships arriving at the city’s coast to adjust their chronometers. The director of the Colaba Observatory (which moved to Alibaug), astronomer Nanabhoy Ardeshir Framji Moos was also the Director of Time Communication of the Harbour. With a desire to standardise, as of June 10, 1900, he set Port Signal Time to GMT +5 hours.

When you read their studies and speak with Masselos or Krishnan, they present a city in 1900 which was divided into a grid of time standards — clock towers, church bells, time signals, mill sirens and the railways were all part of this patchwork. It was like moving between time zones, while you were still very much in the same city.

It is one of reasons that drew noted photographer Chirodeep Chaudhuri to search for public clocks in the city. Working on a personal documentation project of these sentinels of time since 1996, Chaudhuri was introduced to Masselos’ research on Bombay Time by historian Sharada Dwivedi. “I was drawn by the social aspects of technology — how it shapes society and how society moulds itself around new technology, including these clocks,” he says.

Bring in the standard

It may seem that those who ran empires, and scientists and astronomers were but having a ball of a time back then — tinkering with standards. But, the matter of time is hardly a comical one, say the historians. “Until the turn of the century, half an hour or so didn’t even matter. But, with the use of telegraphs, there was a greater need for accuracy. And, that is the point of industrialisation. It means that people, money and machines can be controlled, calculated and assessed,” says Krishnan.

Masselos states the fundamental: Who controlled the clock, controlled time in Bombay. In 1905, a new time standard, set by the longitude through the Allahabad Observatory — GMT +5 hours 30 minutes — was effected. Madras Time phased out. On July 1, 1905, Indian Standard Time (IST), which is followed till date, was implemented country-wide and was adopted by Indian railway companies and government offices in the Bombay Presidency — except, of course, aamchi Bombay. Bombay refused to add 39 minutes to its time standard and keep up with IST.

Public bazaar clocks, which were run by the municipal corporation, continued to signal Bombay Time. It became the city’s way of resisting colonial power. ‘The clock time of the city was effectively split between officialdom and the Indian public,” writes Krishnan. The 4,500 workers at the Jacob Sassoon Mill in Lalbaug (now India United Mill No. 1) smashed the clock and went on strike when the time was changed from 5.30 am to 6.09 am.

While reasons for the municipal corporation giving in to IST are not fully clear, one speculation is the 1950 integration of Bombay City with Suburban Bombay — which had obligingly followed Madras Time and IST. Once that was done, there was no option but to keep up with the rest of the nation.

“However, Bombay Time is a brilliant excuse to turn up late,” says Masselos, laughing hard over the phone, “We should try not to make it disappear.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!