The following extract is taken from Pinki Virani’s book 'Aruna’s Story: The True Account of a Rape and its Aftermath'. Aruna died on Monday, at KEM Hospital in Mumbai, after being in coma for 42 years

Aruna Shanbaug is not blessed. She is partially brain dead. She is blind. She cannot speak. She has atrophying bones, wasting muscles. The joints at her fingers, her wrists, the knees, her ankles are bending inwards. To try and straighten them is to cause her pain. She feels pain, this part of her brain is a sly survivor, it continues to be healthily alive. She gets her periods, these are excruciatingly painful periods.

ADVERTISEMENT

Complete coverage: Peace, at last, for Mumbai nurse Aruna Shanbaug

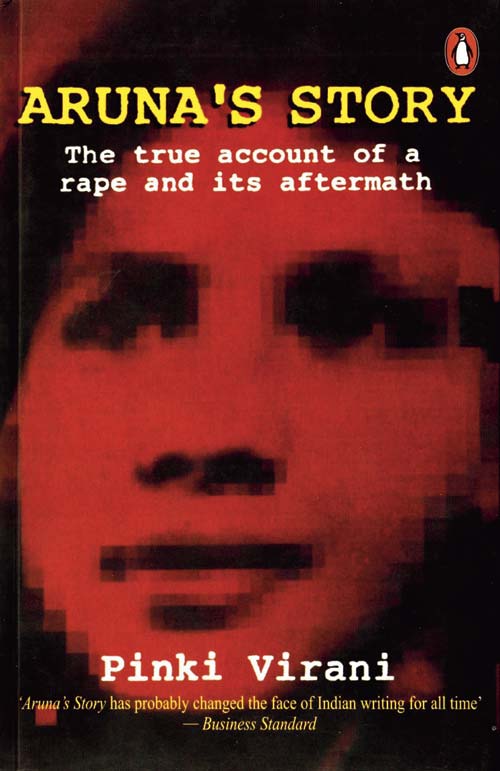

In this picture clicked in 2005, Aruna Shanbaug is seen at her hospital bed at KEM Hospital. File pic/Rane Ashish

She is in this ‘convalescent home’, in a far-flung Bombay suburb, from 10 February of this year, 1977. She is drugged, moaning and a bloody mess. Her periods have arrived. She also has the beginnings of several bed sores, lice in her hair and filth on her body including carelessly cleaned flecks of drying faeces. She is wasting away, but her spirit is not allowing this process to be rapid enough to invite an early death.

Also Read: Mumbai nurse Aruna Shanbaug, who was in coma since 1973, passes away

Her nurse colleagues from KEM have come to visit, they take one look at her and mobilize assistance. A social worker is contacted to speak to some politicians, letters are written to newspapers, telephone calls organized from ostensible strangers to voice their objection to the dean of KEM Hospital and the municipal commissioner of the Bombay Municipal Corporation.

The BMC buckles, not in the face of such organized public opinion but with the thought that now if Aruna Shanbaug dies it will be known that it was the city corporation which ordered what has started amounting to an excruciatingly slow and pain-wracked murder. On 10 March 1977, exactly a month later, Aruna comes back home to her hospital bed attached to ward 4.

She is cleaned up thoroughly, medicated, bandaged. Her hair is completely shaved off because of the lice. Her position is changed every two hours, she keeps going back to her favoured foetal postion. Soon she is put on FDHP plus two eggs, Full Diet High Protein. She screams. She laughs. She shouts. She weeps. Things are back to normal in the life of twenty-nine-year-old staff nurse Aruna Shanbaug.

Dr Sundeep Sardesai stands at Aruna’s bedside looking down at her, he hesitates, then he pulls up the stool which has come with her from ward 33 and sits on it. He does not take her hand in his, she is knocked out with the anti-convulsants that have had to be administered over the last twenty-four hours. He speaks to her, in a very low voice, just a few sentences compared with his earlier long, detailed chats with her.

‘Tomorrow is the first of May, my wedding day. My family and friends have fixed this marriage for me. She is a genuinely nice woman, I should not do anything to hurt her. I cannot see you after this. I will be coming to KEM but I will not visit you. There will be talk about this and my marriage around your bed, you will have to listen to it, I’m sorry. If you can, please forgive me.’

Dr Sardesai gets up from the stool and goes to the little locker on the other side of her bed. He looks for the new packet of bindis he had purchased and put into her locker as soon as he had come to know of her return to KEM. The packet isn’t there, he rummages around the locker, he cannot find it, he looks helplessly around the room.

He goes to the door, turns around and looks at Aruna, walks swiftly back to her bed and folds her limp body into his arms, her arms fall by her sides. He cradles her head in his palm, kisses her cold, unresponsive lips. This is the first time in their four-year-old relationship that he has kissed her. The salt of someone’s tears sting his lips. And then he is gone. This time, forever.

Nephrology specialist and nurses in charge, Dr Vidya Acharya is trying to explain one simple point to the staff nurses — that they have become far too possessive of Aruna Shanbaug. ‘I understand that she is your colleague and your feelings run strong because of all that she has gone through. But you must also understand that she is a patient.’

‘You want us to be indifferent to her?’

‘You are using the wrong word; you are not indifferent to patients in KEM, at least not as yet. You need to be detached with Aruna’s treatment just like you are with that of other patients.’

‘If we had been detached she would have suffered very badly before dying in some rubbish bin for human refuse.’

‘All credit and I do not say this because we are having this conversation now goes to the nurses of KEM for Aruna Shanbaug’s maximum rate of recovery. But why must you surcharge the atmosphere with so much possessiveness and anger when we even think of trying a new line of treatment on her?’

‘She is not a medical guinea pig that every time some new treatment for the brain is heard of, you all should run and try out some experiments on her.’

‘We tried a new method of physiotherapy. You all stopped it because it hurt her, obviously it will hurt, she has not used her limbs in a while. We tried taking her out of the room on a wheelchair, she screamed, you all stopped it. Concern is all very well but does it ever occur to you that you might be a stumbling block in her treatment?’

‘Like we were a stumbling block when you all looked the other way when the BMC tried to kill her?’

‘The point right now is this. We are doctors, each time academic friends and colleagues of ours from all over the world come to Bombay we invite them to KEM to specifically examine Aruna Shanbaug. Some of them make suggestions, you all take kindly to only a very few of these. Presently there is this Swedish team in the city, visiting at Bombay Hospital, and we are requesting them to come over and see Aruna. Please do not question their motives or look at them with suspicion, they are professionals, treat them with the respect they deserve. Please assist them in her examination.’

The Swedish team suggests the stimulation of Aruna’s brain through mild shocks with sensors and probes.

‘She is not your laboratory monkey. Nor is she your medical basket-case where everyone can toss in their untried ideas.’ So saying, the nurses veto the suggestion.

Dr Acharya sighs, people can be difficult to reach.

May 1978.

It is hot, so hot that the air itself seems to sweat. Senior assistant matron Kusum Upadhyay wipes her brow and tries concentrating on the otherwise simple task at hand, the rescheduling of nurse shifts. It is not helping that she can hear Aruna shouting from down the corridor. She has been shouting since the morning.

Sister Upadhyay pushes back her chair and leaves her office to walk down the corridor. She is met half-way by trainee nurse Christine Gomes. ‘Sister, I was coming to see you.’

‘What is it?’

‘That nurse, uh Aruna Shanbaug, she has been shouting from the morning.’

‘I am aware of it.’

‘The patients in ward 4 are getting very agitated.’

‘I was on my way to her room, you can come with me if you like.’

The young Christine Gomes falls in step with her senior assistant matron, she has seen Aruna Shanbaug once before, she had peeped into the room when she was asleep. However, nothing has prepared her for the sight of a bony, wild-eyed woman with hypertonic limbs screaming hoarsely and continuously. Without realizing it Christine clutches Sister Upadhyay’s arm.

‘Aruna? Aruna! Stop this, you are disturbing other patients.’

There is an immediate cessation of sound in the darkened room. Sister Upadhyay briskly pulls back the curtains, opens the window and turns up the fan. ‘I thought as much, you were shouting away because you wanted some attention, well what is it?’

Aruna cringes away from the afternoon light pouring into her room, she wails aloud. The trainee nurse stands in a corner rubbing her forearms, she has goose pimples. Sister Upadhyay bustles about, straightening the bedsheet, changing Aruna’s sanitary napkin made out of a folded piece of padded cloth.

‘I know you are in pain because you have your periods.

But such pain is to be borne.’

She gestures to the young girl, let us leave the room.

Outside in the corridor, Christine meekly asks of her senior assistant matron, ‘Can I please ask you a question?’

Sister Upadhyay hesitates, then decides she will answer this child’s questions on Aruna Shanbaug, God knows there are lessons in this for all of us. ‘I’m going to ward 4 on a round. You can walk with me and we can talk. Come.’

‘Does she always shout like this when she wants attention?’

‘When it gets very bad she does. Earlier there were so many of her batchmates, even her immediate juniors, who would make it a point to collect around her bed and chat with each other so that she could feel like a part of them. Life is so strange, when she was a working staff nurse she hardly socialized at this level with her colleagues, she kept mostly to herself. Anyway, now most of her colleagues have gone, they are married, they have moved to private hospitals. The new ones, like you, don’t know her at all.’

‘You were among them, Sister Upadhyay, when they shifted her to that other place?’

‘You are asking whether I was in agreement about her being shifted?’

Christine is frank. ‘Yes.’

‘I felt that it was better if our person was under our care.

But I saw it from the administration’s point of view too, they were not wrong in wanting a bed to be vacant for patients more deserving of treatment.’

‘You mean because she is brain dead she is not deserving of treatment?’

‘She is not entirely brain dead. I cannot answer the rest of your question because it is an extremely subjective matter.

A decision on this subject is an outcome of a very individual thought process . . . I think it is very ironic, the more medical sciences advance the more heated will be the debate on mercy killing in the future.’

‘Is that what it was supposed to be for her when she was sent away, mercy killing?’

‘It could be looked at like that as well.’

‘Do you think she would have been better off dead?’

‘I told you, answers to such questions can only be very subjective. But I do not think there can be too many people in this world who want to suffer, be a burden on others including their own children, be dependent on a breathing machine and then die physically several years later.’

Aruna starts shouting again, a patient in ward 4 complains loudly about it.

‘I am told that some senior nurses feel this would never have happened to her if she had had to obey orders?’

A question rephrased, an answer in contemporarily structured sentences; but the dilemma continues to echo for Indian women over generations.

Sister Upadhyay smiles sadly, ‘How often this question gets asked in so many different ways. The answer is the same but somehow this reply keeps refusing to fall into place for you young girls. Let me put it this way.

In English the words are man and woman, this does not symbolically signify the difference as much as our Hindi words do, nar aur nari. The woman has that extra letter because she has to take that extra precaution. I know it will sound old-fashioned to you. It sounded very out-of-date to Aruna when I told her she should not change in the CVTC basement. You young girls don’t want to take advice from elder, more experienced women because you think you are part of a more modern, better world. Some things do not change, in fact men become more bestial as women become more like them.’

Christine crinkles her eyebrows trying to absorb it all.

‘Sorry Sister I did not understand. Are you saying there should be no progress for women?’

‘What is the meaning of progress? How do you define it?

And at what price do you want this progress? At the cost of your virtue? The way things are going today’s generation might think of virtue as merely that easily discardable small piece of skin. But because I, an old woman, am saying this you will laugh at me when I tell you that for a woman virtue is connected with self-respect. Virtue goes beyond a hymen hidden in one part of a woman’s body, it is also her mind, and the resultant way she looks at the world.’

Aruna’s shouts pierce the ward, more patients fret and grumble. Sister Upadhyay sighs, ‘Come with me, you can give her the pain-killer injection she has been asking for from the morning.’

Trainee nurse Christine Gomes proficiently administers the injection. Sister Upadhyay smiles her approval. Outside the door Christine once again asks a question. ‘Last one Sister.

Why is God making her suffer like this?’

‘Do you believe in rebirth?’

‘Christ rose from the dead. But I don’t know for myself, I’ve never thought about it.’

‘According to us Hindus there are rebirths. Perhaps she is paying for what she did in her last life. Perhaps, like your Jesus Christ, she is paying for all our sins. And if none of these thoughts can give us any comfort, perhaps we must just finally believe that there is no God, Aruna Shanbaug’s plight is proof of it.’

Extracted with permission from: Aruna’s Story

Author: Pinki Virani

Publisher: Penguin Books India

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!