Heramb Wagle’s grandmother travelled extensively for his treatment and even started a school to educate him, ensuring that the 20-year-old can now earn his own living

“Majhya aai la mi nako hoto, ti majhyashi bolat nahi. Majhay vadil majhyashi bolat nahi, tey mala avadtat, pan tyanaa mee avdat nahi,” (My mother did not want me, she does not talk to me. My father also avoids me. I love him, but he does not even like me),” says Heramb Wagle from Nashik.

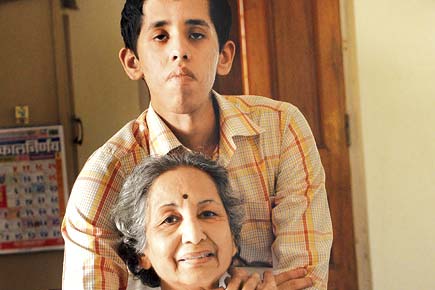

Medha Wagle with grandson Heramb. Pics/Nimesh Dave

Being able to even string that sentence together does not come easy to the 20-year-old, and not just because of the emotional toll that it takes.

![]()

Early in his life, Heramb was diagnosed with mental retardation and autism and, even before his diagnosis, his parents refused to take him home as an infant because his father, Sameer, an Air Force pilot (now retired) and mother, Seema, were too busy with their careers.

Medha Wagle with Heramb

Abandoned by his parents when he was just a year-and-a-half old, Heramb found the love that he so desperately needed in the welcoming embrace of his paternal grandmother, Medha Wagle, who stood by him like a rock.

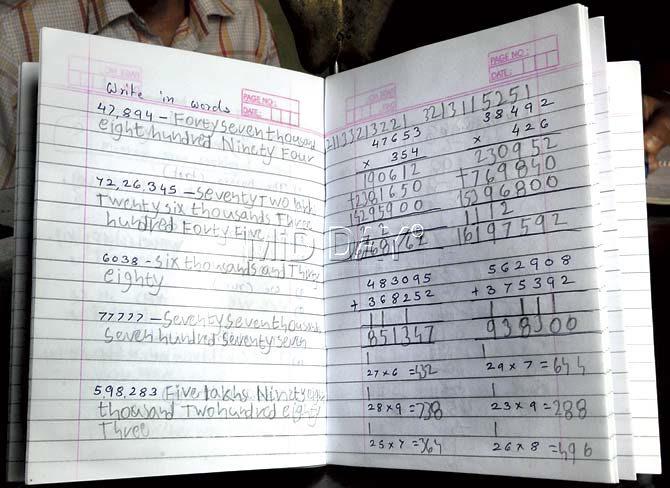

Heramb learnt to make paper bags as part of his occupational therapy. He now earns anywhere between Rs 900 and Rs 1,200 a month selling them

While his parents didn’t come to his aid emotionally or financially, Medha, who holds a bachelors degree in psychology herself, got Heramb diagnosed, read up on his condition and even travelled back and forth extensively between Nashik and Mumbai to ensure that he got the treatment and education that he needed.

Medha with Heramb and some other former students of her school for special children, which she is having to shut down because a lack of funds

Despite her old age, Medha even started a school to help educate Heramb and others like him, and her heroic efforts and perseverance have finally paid off, for Heramb can not only write and type a little bit now, he also makes a living for himself by selling paper bags.

This exercise book is proof of the remarkable progress that Heramb has made. He can write in English and is also picking up Marathi words

Not a priority

“When Heramb was born in December 1994, Seema was reluctant to take him home, because she was upset that the baby had come into her life too soon after marriage,” 74-year-old Medha told mid-day. Two months after Heramb’s birth, Sameer got a posting in Allahabad and the trio left Nashik.

Medha would call up to inquire about Heramb, and Seema would tell her that the child slept most of the time and his development was slow. This worried Medha, who then visited the family in August 1995 and found out for herself that Heramb had fallen around six times when he was between two and eight months old.

Soon, Seema got pregnant with a second child. The family came to Nashik for the delivery of the child, a daughter, and lived with Medha for six months thereafter. When it was time for Sameer and his family to return to Allahabad in June 1996, Medha suggested that Heramb be left with her as it would be difficult for Seema to manage both the children, which Seema readily agreed to.

A special child

When Heramb was around three years old, Medha noticed that he was unlike a child of his age. “Heramb did not maintain eye contact and did not say even a few words. He had difficulty expressing his needs, on account of which he remained hypoactive and lost in his own world, for hours.

All this led me to suspect that there was something wrong with him,” she said. When mid-day asked her why she did not take Heramb to a doctor right then, considering that he was displaying symptoms of slow development, Medha said, “I thought that was a passing phase, because not all children grow or show development at the same pace.”

During this period, Medha says, the parents showed no interest in enquiring about his progress. When Heramb was three, it was time for him to go to school, and Medha asked Sameer to take him to Hyderabad, where he was posted then, so Heramb could join a school there.

The parents took the child, but Medha says Heramb was dropped back with her within a few months, in May 1998. Sameer suggested that Medha enrol Heramb to school as he had been living with her for a long time. When Heramb was admitted to a regular school in Nashik, it was brought to Medha’s notice that he was unlike other children in the class.

Medha said Heramb’s parents were informed about this, but they remained aloof, and did not even bother to visit him. Medha then started meeting paediatricians, one of whom referred her to a psychologist. During one such consultation in Mumbai, when Heramb was four-and-a-half years old, a developmental test was conducted by Bandra-based psychologist Narendra Kinger, who said that Heramb’s mental development was one-and-a-half years behind kids his age. The psychologist suggested that Heramb should continue in a regular school.

When Heramb was in Sr KG in his school, however, Medha learnt that educators were neglecting him and decided to withdraw him from there in 1998. She went to a psychiatrist in Nashik, who advised that she should admit him to a Marathi-medium school.

Though his learning abilities showed improvement in this school, he could not read and write in Marathi. After he finished Std I, he was withdrawn from that school as well and Medha decided to get him admitted to a special school. Medha hit a roadblock due to a lack of centres and therapists for special children in Nashik.

Stating that she is not the kind who gives up, Medha said she decided to gather more information about special children. A US-based relative, who was also a paediatrician, sent her books on the subject and also counselled Medha on how to take care of Heramb.

Mumbai calling

Medha, who graduated of Ramnarain Ruia College in Matunga, decided to come to the city in 1999 and touch base with her college friends to seek their help for getting Heramb treated.

“I was lucky to meet a classmate who was working at the All Indian Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AIIPMR) at Haji Ali, who suggested that I observe how the special children were trained there. I took tips from there and even visited a few other similar centres in Mumbai. I was happy that I was able to handle Heramb’s condition and decided to teach him at home.”

In her early 60s, Medha was emboldened to start a school for the remedial education for special children in Nashik, which lacked such facilities. Uttkarsh Education Society began functioning in 2000 from a rental premises in Nashik, the monthly rent for which Rs 4,000 was paid by Medha from her savings.

While Heramb was the only student in the school initially, three or four other special children joined within a couple of months. Soon, around 24 children had enrolled in the school, which had four trained teachers. “The inspiration for the school was my grandson. I wanted it to be a source of help to special children by giving them a platform to grow and develop and their parents,” said Medha.

The last mile

Attending an educational conference in Pune in 2006, Medha heard about stem cell therapy when she came in contact with Dr Nandini Gokulchandran, Deputy Director, NeuroGen Brain and Spine Institute in Nerul, Navi Mumbai. Medha invited Dr Gokulchandran to her school to conduct an awareness programme.

On Dr Gokulchandran’s advice, Medha took Heramb, who was 18 years old at the time, to the institute in Nerul, where he underwent stem cell therapy on December 26, 2011. The cost for the therapy, which ran into lakhs, was borne by Medha. Subsequently, Heramb was put on a combination programme of occupational therapy, physiotherapy, speech therapy and psychological counselling.

The programme began to show results over time, said Medha, adding, “His fine motor skills have improved and he understands things a lot better now. He has even started writing in English and is learning a few Marathi words. His attention span has also improved and he is becoming more independent. This, in itself, is a huge relief,” said the 74-year-old, a smile splitting her face for the first time since she began talking.

School to shut

The school that Medha started did well for eight years. However, she found it difficult to sustain it and pay salaries to the teachers and staff. “I approached the state government for financial aid, but did get any,” she says. On account of limited funds and her advancing age, Medha handed over the running of the school to a teacher she was acquainted with in 2013.

However, the teacher could run the school for only a year and she handed the school back to Medha, who is now in the process of shutting it down. Medha continued to teach Heramb at home. Among the other students, a few went to other schools within the district, while a few had to discontinue their studies.

The 74-year-old Medha said she is worried about the future of Heramb, given her advancing age and ill health. She plans to sell off her house in Nashik and shift to an old-age home in Pune, with her elder son Girish (52) and Heramb. The old age home has caretakers to look after Heramb.

Heramb has learnt how to make paper bags and also learns typing on his personal computer. He takes the paper bags to a local chemist, and is paid a few hundred rupees for them, which he deposits in his bank account. “Heramb can do the bank work, like filling slip books and depositing the cash, by himself,” says Medha, beaming with pride.

“I am sharing my story with mid-day so that no other child goes through what Heramb has had to. Every child needs the love and care of his or her parents and grandparents, especially a child with special needs,” said Medha.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!